How Ableton Pushes Women Forward In Music Tech

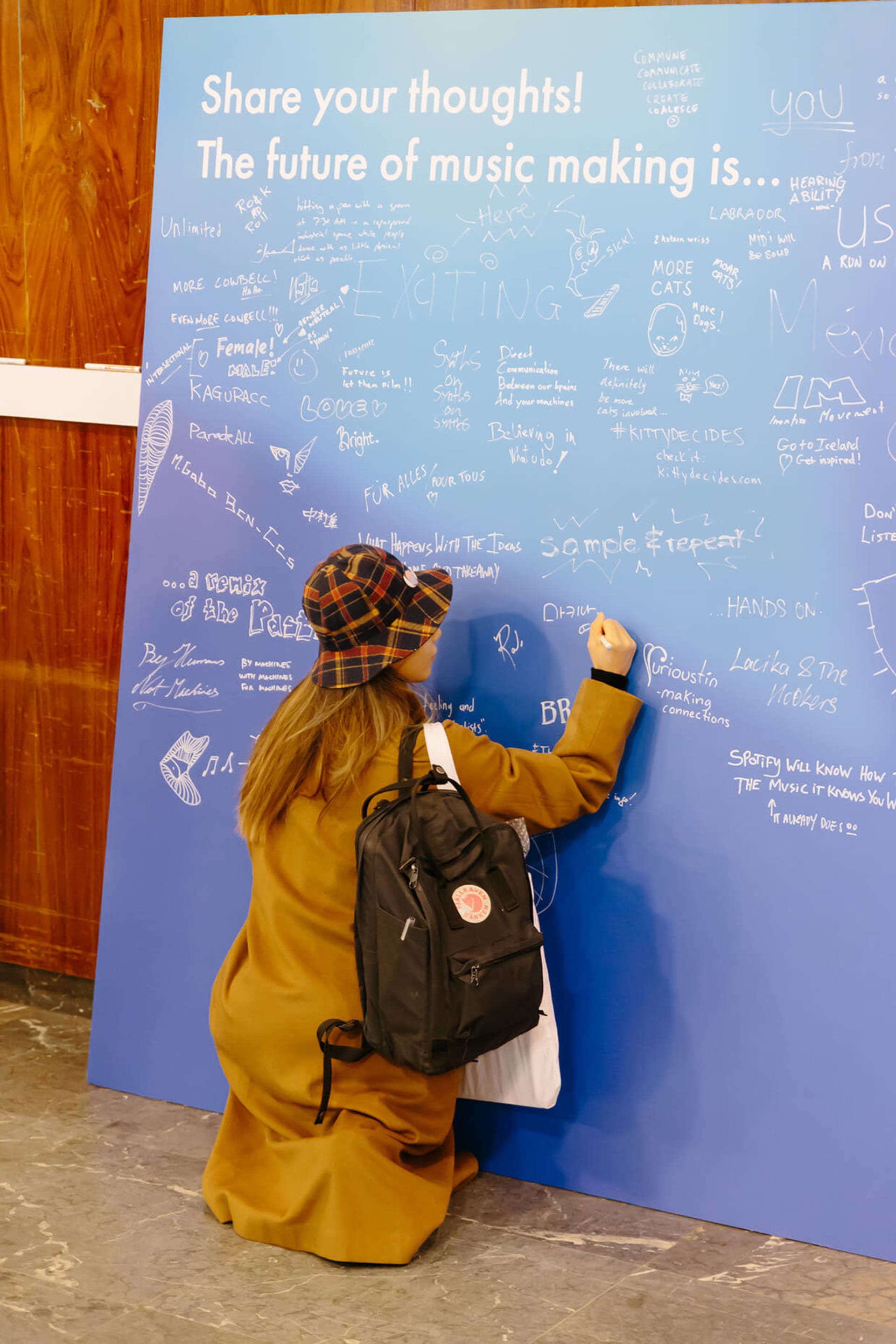

This year’s edition of Ableton’s annual Loop summit served as much more than an elaborate product launch—especially compared to its debut event in 2015. The three-day program of presentations, workshops, installations, club nights and concert performances at Berlin’s GDR-era complex Funkhaus also demonstrated a visible commitment to gender diversity across its attendees, presenters, panelists, moderators and installation artists. Many of the strongest throughline themes—the critical reading of the history and culture of creative expression; the fostering of diverse perspectives in the creation and use of creative technology; the power of collaboration and exchange—emerged implicitly and explicitly through the perspectives of its female participants. We spoke with some of these women, including Loop’s organizers and presenters, to tease out these gender-centric topics a little further.

Michelle O’Brien, Loop’s Program Manager and Creative Producer

Rather than publicizing Loop’s specific diversity targets and strategies, we take the philosophy of “Don’t say; do!” to let our actions speak louder than our words. I will say that our work on diversity at Loop to date has not happened by accident; it has required a buy-in from all stakeholders at every step of the planning and development phases and an undying commitment from the entire Loop team.

Drawing out gendered themes surrounding women and technology could be viewed as one of the outcomes of combining our programming principles with this focus. We aim to see an increasing diversity of presenters and attendees with each iteration of Loop. A healthy music-making community is one with a diversity of voices, stories and perspectives, musical genres, ages, levels of ability, cultural identity and so much more. Loop is a reflection of how we envision the international music-making community to be—not always an exact reflection of how it might currently appear.

We do not practice gender tokenism (or any kind of minority tokenism for that matter) in the Loop program. For example, we do not curate gender-specific programming strands or events. Diversity of gender is instead intrinsic to and engrained in the core Loop program, offering one perspective of many, from which wider conversations surrounding music making can stem. We’re proud of the results to date, but there is still so much more work to be done. Diversity will continue to play an increasingly important part of Loop moving forward.

Tara Rodgers, composer, writer, Loop presenter, educator and author of Pink Noises: Women On Electronic Music And Sound.

I became interested in history as an undergraduate when I studied popular culture and trained with a historian. That was my first exposure to doing archival research, not necessarily related to music, but about how you go into archives and find information that teaches you so much about the present. I didn’t turn back to archival research until about 10 years later to investigate the history of synthesizers.

In between, I started the Pink Noises website in 2000. It featured interviews with women who DJ and make electronic music and provided information on music production in a way that tried to make that information accessible to everybody—including beginners. The problem of sexism and misogyny in online music technology forums is still an issue, but also there’s a general hostility to beginners. There can be a lot of posturing and a performance of expertise in those spaces that isn’t welcoming.

In my own career, the timing of the advent of internet was exciting for feminist projects because you could use that to create these new spaces for discussion and dialog. For a while, Pink Noises included an active discussion board that was one of the first online communities for women in electronic music alongside female:pressure. It was a way to connect women in the international field and to provide space for discussion and networking. Pink Noises evolved into a book project, which wrapped up in 2010.

The research I presented at Loop on the history of electronic sound was the subject of my PhD dissertation. That’s really when I began focusing on these questions of language and representation in textbooks, product manuals and other technical information about sound. I explore them like a form of literature. There’s a poetics to it, and it’s deeply cultural and historical.

I try to connect the dots between technical information that’s also historical with knowledge about sound in the present. I’m interested in how ideas with a very long history inform the designs of contemporary instruments and the creative work that musicians do now. I also focus in on the politics of how histories are written and the politics of creative expression. This was true with Pink Noises as well. I think all of my writing is in some way aimed at examining or encouraging musical creativity, especially as it intersects with technology. For inspiration I always go back to writings by Adrienne Rich and Audre Lorde on arts and politics and on creative expression as vital for ourselves and our communities.

Loop is a reflection of how we envision the international music-making community to be—not always an exact reflection of how it might currently appear.

Mint booking and promotional agency co-founder Ena Lind and Katarina Becic, Ableton’s Head Of Social Channels, who both organized the “Perspectives On Collaborative Approaches Breakfast” at Loop.

Ena Lind: Zoe Rasch and I started Mint four years to support women in electronic music because we didn’t feel represented. We started with a club night, but after a year we thought we could do more than just book people and present them to a dancing audience. So we started Mint Campus with workshops, did a short film series, organized networking dinners and other things, some with the support of Musicboard Berlin. This year we started doing panels, and next year we want to put out our first Mint record. We have eight artists on our roster, so we’re going to have four of them on the vinyl. Then we want to start touring with our “family” where all of us go back-to-back all night.

There are many projects like Mint that have different angles and the same goal. That’s the great thing about social media: we already know most of these women-focused collectives; we might not have met, but we know about each other, so when we travel it makes sense to do things together. That’s why the topic of today’s panel—collaborations—was not only about common musical interests, but all kinds of collaborations—especially among women. There hasn’t been a lot of working together until recently because there was so little space for everybody; when they were on top or on the way up, it was all elbows. Now it feels like people are starting to understand that we can get so much further if we work together.

Katarina Becic: About half a year ago, we came up with the idea to create an event where we would gather female talent in a panel, as we wanted to address the issue of low representation of female producers. These low numbers are especially evident in our user base, which is predominantly male at the moment. We have a long way to go to get to a 50:50 split. Last year at Loop we partnered with female:pressure, and this year we teamed up with Mint Berlin, as we share the same ideas about how to represent female music-makers. Our focus wasn’t on confronting this inequality directly, but rather to show that women can be equally competent in all areas of music-making. However, we felt that women could collaborate more, and that’s why we chose this as a topic for our panel.

Also, through my recent research, I realized the importance of the notion of “by women, for women,” which is why we chose to have all-female panel for this discussion. In my role as a Head Of Social Channels, I’m in a position to be the ears and the voice of Ableton, which allowed me to witness some instances where female producers were verbally bullied on the basis of their gender. This behavior needs to change, and I am pleased that at Ableton we can help to surface more female talent and enable more women to experience the satisfaction of making music.

Sougwen Chung, interdisciplinary artist and presenter at Loop.

I find that technology can be an incredibly sophisticated apparatus for the translation of human experiences. I’m excited to explore that more, and I’ve seen some really interesting artists who use brain waves and breath and all these somewhat-invisible or unseen bodily inputs to control the environment that they’re in. That also extends this intimacy of input into something that can be augmented by these technologies. Audio/visuals are very explicit at this point in time; there’s usually this frame that the visuals rest in and the performer is in the front, and to be quite honest, a lot of times you’re not really sure what everyone’s doing. I would love to see more explicitness in that environment and even a bit more vulnerability from the performer.

I’ve been joking with some of my friends and colleagues that right now, my robotic arm performance system [which mimics and interprets the user’s drawing gestures and techniques to illustrate in sync] D.O.U.G._1 (Drawing Operations Unit: Generation 1) as a collaborator is a bit like a drunk dude who forgets things right after they happen. That’s the system right now; it doesn’t include as much memory and data-gathering as the next generation of the project will. One reason I’m really excited about the second generation is that it’ll be able to learn more about different drawing styles on the level of code and algorithms, and then use that to design behaviors. Once D.O.U.G. remembers more, he’ll be able to reflect more of these very nuanced and complex systems, as well as the collective agency of the people who are also going to design its behavior.

In some ways this project is a response to the question of authorship, which is another really central issue of our generation, like remix culture. When content is digitized it can be infinitely proliferated, but right now, with style transfer, we’re also finding that the form can be separated from the content and then infinitely proliferated. Style transfer is very much about the completed style of the image and then transferring that to another thing. What I’m hoping to do here is extract the process of it and then utilize that as a collaborative tool. The system of D.O.U.G.’s drawing memory could help us learn more about what it is to create or draw ourselves.

Elysia Crampton, experimental electronic musician and presenter at Loop.

My mother is full Native American from an Aymara background, and my father is a straight-up American man of Irish descent. I always “presented” genetically closer to my mother. My father is a minister and still works for the Protestant church, and growing up queer there was not only a disconnect from him because of my appearance but also because of the religiosity and the belief that queer bodies are a sin. I lived in a lot of denial just trying to survive, belong and fit in. I once called myself a Christian—in fact, I was rebaptised in 2012, because I had this born-again experience that I couldn’t account for. That’s what I tried to speak of in my presentation at Loop with the term ch’ixi, that there are contradictions that are housed together. It’s kind of like yin and yang, except that they’re not peaceful in harmony. They just have to coexist in a way.

I related it to Judeo-Christianity, but living for small periods of time in Bolivia and reconnecting with my grandfather and with the queer community there I came to understand a deeper part of my spirituality that I relegated as pagan before—as opposed to this world of black and white. Why would I want such a crusty old pagan god? It almost seemed to be too symbolic, just fashion, too exterior. But I think it’s incredible how my indigenous family and the indigenous community over there embraced me as transgender. It allowed me to finally live openly from what had been this gender non-conforming conflict. Nothing in the binary would have worked. It fundamentally had no place for me.

The idea of embodiment as it relates to queer being and this whole oral and ostensibly female Andean tradition was not centered in recording history in writing. It was on one that was worn, one that was carried, one that was spoken. I think about the legacy that I carry in spite of its validation on the written page. In my presentation I was trying to account for that dimension of oral history, because my music career is not just giving me economic mobility and stability to access research time, but I also use it as a language tool. Even before I identified with the Aymaran deity Choque Chinchay, or as a Christian, I would call my writing music my “praying to God.” That dimension was always deeply embedded there and it’s always been part of it.

It was mainly through the music that I also came to uncover those things. I like the word “interanimative,” which comes out of the theology tradition. I think it’s a great word for theory. It’s ongoing. That’s what I love about music and being a visible musician, because I learn so much more from the audience’s gaze. All that decolonial work of theorizing and speculating and understanding the music as a reaction, as a descriptor, or as a small embodiment of my reality tells me something about that reality. Language and the other tools I have won’t suffice to do.

Published December 08, 2016.