Ariel Kalma Speaks To Bing & Ruth’s David Moore About The Strength of Limitations

David Moore

Ariel Kalma and David Moore have never met, but they have a lot in common. They’ve both been inducted into the RVNG family (which, full disclosure, includes Electronic Beats staff writer Mark Smith of Gardland), they both work with ambient structures and classical instruments, and we’re pretty sure that neither would want to classify their music as “ambient” or “classical.” Kalma’s inaugural RVNG release, a compilation of his productions from the 1970s called An Evolutionary Music, marries saxophone drones and exploratory electronics in hypnotic and full-bodied textures. Moore’s recent compositions with the ensemble Bing & Ruth on Tomorrow Was The Golden Age are achingly subtle continuations of the sonic palette founded by Steve Reich and Brian Eno. When we rang them on Skype, it was morning David’s home city New York and evening where Kalma is based in Sydney, and although they’re a world away and a generation apart, the two connected over the fundamental questions of writing music.

Ariel Kalma: Let me ask you David, how is it being a musician making a living in New York?

David Moore: It’s really fun, but also can be very hard and frustrating. I think it’s hard to be anything in New York, but being a musician is especially tough. There’s a lot of musicians and so many resources that it can be overwhelming. But I’ve sort of figured it out, and it’s too late for me to do anything else now.

AK: No, no, no, that’s not right. It’s not too late. Look at me, I’ve changed so many times my whole life. Let me give you this, David: too late does not exist, okay? Take it from my white hair here that you can change at any time.

DM: I do travel quite a bit, too, but I always have a hard time writing music while I’m travelling. It’s almost this sense of trying to experience as much as I can, and then when I get home to New York, I process everything that I went through and it all comes out. So I’m sure it is all colored by New York and the sense of where I am, but it certainly doesn’t feel that way to me in a larger sense.

AK: I see music as the inside expression of the outside world, and therefore, what we experience by being in a place or travelling, it’s the expression. Personally, I did not feel when I heard your music that it was from New York. I would have thought that you live in a garden!

DM: I wish!

AK: My story is that I felt I had to get out of Paris when I was younger, because I was depressed. I was getting depressed with grey walls and streets. My music was trying to escaping of this greyness. Beyond those words though, composing is for me the inner world. “How do I grab the outside world and churn it inside and project a music?”

DM: You are always going to have some sort of a relationship with where you are physically when you’re writing. For me, composing is reaching for something. New York, for me, is a very difficult place to live. It’s very active and busy and I don’t like it, and that’s strangely why I love living here. It gives me a reason to put myself out there, something to want. Certainly, there are times where I wished I lived in a garden.

AK: Your musical garden is very beautiful, David! For me, the important thing is to be completely immersed in the moment, because this is the only certain thing we have. When we are in the moment, there is no past and there is no future. I constantly ask myself “What’s happening now?” After a while, the ego disappears, and the door opens for pure music. I become more than the separate parts of the self, and when this happens, there is no time.

DM: Well said. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the idea of time, and I don’t know how much I buy into it. I agree with you that it’s just the moment, and everything in the past and in the future doesn’t exist, it’s only right now. I try to make music that feeds me in the right-now, and by doing that, I think you tap into some greater thing that somehow lends itself to being seen as timeless. I don’t care what the sound of 2015 is. It’s always just the sound of me.

I think you have to be careful when you’re getting to close to an extremely established musical genre of any kind, because then you start falling into the way things were done and you do things that way. What I like about what people call “ambient music” is that it takes a different approach to your attention. Music doesn’t have to be this thing that you’re always paying attention to. I put ambient music on in the house in the first few hours of the day at very low volume and I find that it can inform my mood and then inform my thought process subconsciously. For the Bing & Ruth record, I tried to make something that you could put on very low volume and do other things, or if you want to put headphones on and turn it all the way up it will be a different experience. It can serve both purposes, and those are two very real purposes that I need in my life.

AK: I don’t like brackets or definitions, and to be stuck in a genre never fit me. My life is a misfit story. Now, I’m doing tribal music, but it’s not fitting with the “world music” genre and I’m fine with that. I’m a unique individual! “Ambient” comes from the word “ambiance”—it’s something we bathe in. Maybe my record Osmose would qualify as ambient music in that sense, with its rainforest ambiance. But if we define things too precisely, like you were saying, then we fall into traps of the mind, and for me, music is to get out of the mind.

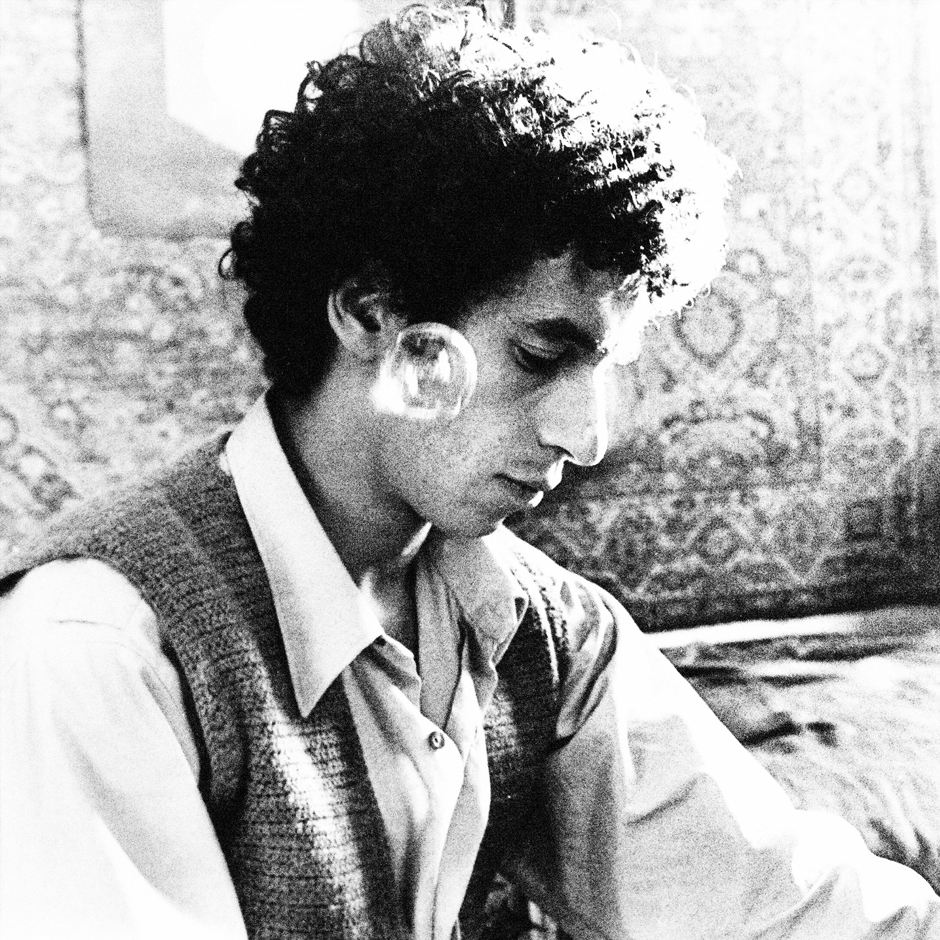

Ariel Kalma

DM: The name “Bing & Ruth” came from a short story from a writer named Amy Hempel, who’s been a big inspiration to me, particularly the idea that the same story can mean two very different things to two different people. There was this attitude of, “Let’s take a story that we want to tell and break it down and remove everything from it that’s specific.” By doing something like this, you can present a piece of music or a story and anyone who brings himself to it can adapt it for their life. I guess people call that minimalism, but to me that’s just good storytelling.

AK: I don’t consider myself a minimalist or a maximalist. I have so many pieces, and I try to evoke a place or a state of being, or I take something more ambiguous. One title is “Dreaming On Red Square,” which has the influence of my part-Russian blood. I’m giving a hint where to look for.

DM: Sometimes you just need to call the piece something—anything.

AK: My problem is that, 40 years later, I sometimes try to change the title. One piece was called “Spanish Flight” from when I was in Paris 40 years ago. I realized that it’s not a good title because Spanish Flight is a powder to enhance sexual functions. I decided that that was not what I wanted to say. I wanted to evoke a flight over Paris at the time, so I’ve started calling it “Paris Flight.” When I remastered these old tapes to produce the new edition for RVNG I had to go back in time. Suddenly, I realized that my limitations in the past were a kind of strength. At that time, I was very limited. For the first album I had a microphone, a wah-wah pedal, a toy keyboard, and a tape recorder with some reverb and delay. So, what do you play with that? Now I have a very powerful studio in my house right here with all these plugins, effects, and synthesizers, and I spend my time choosing sounds and choosing effects. To go back to the archive gave me a sense of trying to make it even more simple.

DM: A big part of my creative process is figuring out a way of overcoming limitations. It’s becoming harder to be limited when there’s more things that you can do having a computer in your house. Sometimes I really miss that feeling of only having two or three elements. It’s like cooking: if you only have two or three things, you’re probably going to make something interesting, but if you have everything, you’ll just follow the recipe. That’s where working with acoustic instruments comes in, because there’s a whole bunch of limitations which are already right there.

AK: I think if you play an instrument, you want naturally to incorporate it. I have lots of compositions with saxophone, for instance. Sometimes I have to force myself to take something else, not to have the imprint of the saxophone, or I transform it in a way which is not so obvious. When I write it’s like a ritual for me. It’s not important what I’m going to do, what’s important is the environment. I have all kind of lights in my room of different colors and different styles. I have lava lamps, blue lights, pink lights, flashing lights, all kinds of things. When I put them on, that’s it, the door is open and I have my story.

The other night, I was sitting here thinking, “I want to play music,” and I heard outside the crickets were so loud and beautiful, so I went and recorded them for 20 minutes, came back, and started improvising with them. I took another sound which I recorded in San Francisco when I was on the highway at a bend of the road. The highway was resonating with the buildings and making a kind of subtle echo reverb. When I put this with the crickets, suddenly I had an atmospheric piece over which I could play.

Ah, by the way David, I really love those clarinets on the album.

DM: Thank you. I grew up playing piano and learned around other people who played real instruments. I’m not talking down on electronic music, it’s just the environment that I grew up learning in. For me, it’s always really been about the player before the actual instrument. So, take the clarinet players—I connect with them on a very deep musical level and I want to use them. If they played trumpet, I’d use trumpets, because it’s the people that I want. The people that I choose to play with have this adventurous side to them, they’re really interested in pushing their instrument as far as they can and finding new ways to make sound. So it’s limiting, but that limitation is really important to how we go about doing it.

AK: Excellent. I sometimes use complete amateurs and I place them in front of a microphone. The human factor is such an important part. I don’t consider myself a “professional”musician. I am an “amateur,” because the root of the word amateur is “amore,” which means love. I prefer to be loving music than to have a job as a musician.

DM: Serge Gainsbourg said sometime something like, “Pick up your instrument and tell yourself a story.” I like that idea. The world today is so connected, and I think it makes it even more important to be in touch with the music of your land, where you’re from. Folk music doesn’t necessarily mean a guitar, a banjo, and folk songs—”folk music” is the music that a culture makes on its own. For me, that music was bluegrass and old time fiddle music. That’s a big part of where I grew up, and it’s a big part of my country and my culture. When I first started Bing & Ruth, I wanted a band that could gather around one microphone like a bluegrass band. A lot of times, folk music is just people being able to make sound together without anything else.

AK: I’m interested in folk music around the world, in the sense that people in Mongolia would gather around with no microphone and play music together, with the horsehair fiddle and their throat singing. So now I’m looking for the archetype of the folk on the global level. What’s the archetype of the people of the Earth? I found in my own research that was is needed is going back to the tribal feeling. I go to the drum circles around the region here and bring my saxophone with me and play music with them, because it’s provoking me to listening very carefully to, for instance, the drums. What is the rhythm and how are they tuned? When it’s a large circle there are lots of tunings.

DM: When you tune your instrument to a tuner, you’re tuning it to the same thing that everybody else has tuned to. But when you’re playing to a small group of people, who knows what it’s going to be. You’re tuning to 10 other people, and you’re making something very unique out of it, and you find weird ways of doing it that are more personal. I go to folk festivals and play banjo and fiddle tunes and I don’t see a tuner all weekend. By the end of it I hook up to the tuner and I’m three steps off, but it’s great! It doesn’t matter as long as you’re together in a way that makes sense, and that everybody’s into it. Why does it matter if you’re “in tune”?

AK: In India, you have 22 steps in a scale not 12, so there is obviously a certain richness in between the notes which we are not accustomed to in our Western minds and ears.

DM: I didn’t really know anything about Indian music until a few years ago. When you see that there’s 22 notes in a scale it’s like, “Oh, well there’s not just 12 notes in a scale, somebody just made that up.” And then you look at a lot of other composers like Harry Partch who made up their own tunings. It’s really wide open, it doesn’t just have to be one way.

AK: I’m going to show you what I’m going to practice when I go on my holidays tomorrow. It’s a chinese flute reed. [Plays a huge slide] Can you see the scope in between the notes?

DM: Awesome!

AK: So you know why I need to practice. With the flute I will make my own “sauce,” to use a culinary term, but what I want is to master a bit what I’m doing. And, David, I am always open for collaboration. Collaboration is a provocation into an unknown future.

Ariel Kalma’s An Evolutionary Music (Original Recordings: 1972 – 1979) and Bing & Ruth’s Tomorrow Was The Golden Age are available now via RVNG Intl.

Published November 13, 2014. Words by laurietompkins.