“Buy me a car and I’ll sign anything”: Gary Numan interviewed

Above: Gary Numan, photographed in Berlin by Luci Lux.

Berlin’s Ramones Museum provides an irritatingly authentic rock and roll atmosphere in which to interview Numan, whose carefully constructed trademark man-machine image has appeared on every one of his album covers since starting his career in 1978 with Tubeway Army. Accompanied by long-time wife Gemma, who he often describes as his guardian angel, Numan was eager to discuss his relief at coming out the other end of a long, dark tunnel of a once declining career. Ahead of his Berlin performance on February 18th, we present our interview by EB editor-in-chief Max Dax, originally featured in the Winter 2013/14 issue of Electronic Beats Magazine.

Gary, you belong to a pioneering group of artists who were extremely influential for electronic music. Do you consider yourself a veteran of sorts?

I’m aware of how old I am, that’s for sure. But talk of influence has only reached my ears in the last fifteen years. For instance, I met Afrika Bambaataa a while ago, and he was explaining to me how he and Soulsonic Force used a lot of my music—Kraftwerk as well—in the formative days when hip-hop became a genre. That was amazing, but I had no idea what was going on.

You weren’t listening to hip-hop back then?

No, no. Looking back, for a long time my interest in music became very narrow. I became very self-obsessed about my career—which, I should add, was in trouble for such a long time. So I listened to music less and less. I think I fell out of love with it. Then in the early nineties I discovered Nine Inch Nails and The Sisters of Mercy and a lot of heavier, more aggressive things that I hadn’t been aware of for some reason. And I loved it. So I started to write very different music from that point and that’s when I started to be interested in other people again. Soon after that the Internet came along. I think about ’95 I started to be actively involved with the Internet and that opened up so much more information. That’s when I really began to read the things that other people were saying about me—people like Trent Reznor or Marilyn Manson—and it kind of just carried on from there. I suddenly found out about other people doing cover versions of my songs, or that they used to sample bits of my songs. A lot of the strength of my gradual renaissance has largely been due to other people being positive about what I’ve done, the effect I’ve had on them. Their praise has introduced me to a new audience. Their props gave me a credibility that’s very difficult to come by.

You can’t buy street cred.

That’s what I’m saying. You don’t even get it from being famous. I certainly didn’t have it when I was selling millions of albums. But via people like Trent the high caliber recommendations from such quality musicians caused so many good things to happen. I mean, in 1979, the NME reviewed my Pleasure Principle album and hated it. But only a few years ago they reevaluated it and called it a classic album of its time.

They probably hated Klaus Nomi, too.

Yeah. There was a hostility to that, an ignorance to white faces and make-up.

When I interviewed Neil Tennant a few issues back, he told me that the beauty of pop music is that it’s all about the surface. Maybe the critics you mention are from a generation that still held the concept of authenticity in such high regard?

I honestly have always seen pop music, even without make-up and image, as artificial. I never was convinced by the reality of any of it. For me, image was essential, as I had so many problems with fear and stage fright. I couldn’t even hold a conversation among friends. And if I was to do a gig in a tiny club, I was terrified of it. Developing my neon cool image was a way of hiding behind something. For me it was a necessary tool, a mechanism to protect myself. But one day, I realized that my image had become me. So it’s a double edged sword: On the one hand it’s good to have a strong image and on the other you have to be careful to stay true to yourself. It’s like having two gears that grate against each other. I realized then that the way you look, the way you sound, the album covers, and even the things you say in public are all parts of the same machinery, and they all need to work together for the whole thing to work properly. I should add though that I don’t care that much about all this nowadays.

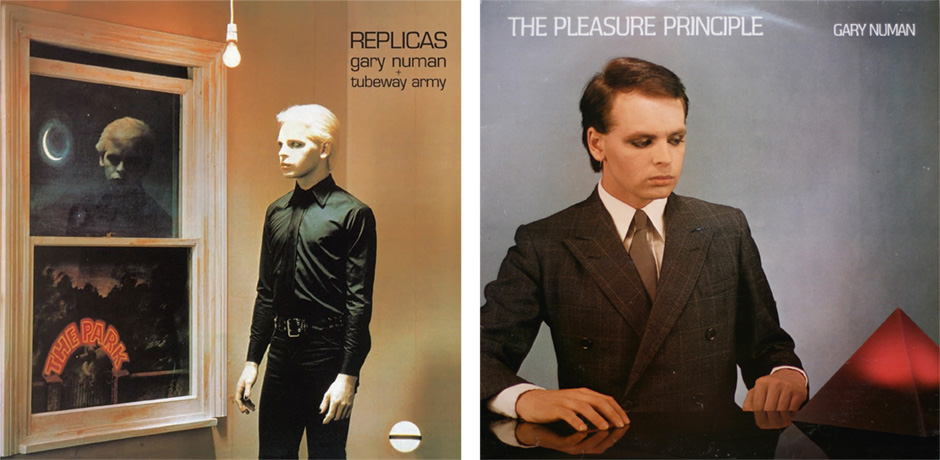

Both The Pleasure Principle and Replicas (Beggars Banquet) were released in 1979, a testament to Gary Numan’s youthful hustle. Part of the “machine music” trilogy, which also included 1980’s Telekon and focused on dystopian themes populated by contemplative cyborgs, The Pleasure Principle contained the Kraftwerk-inspired hit “Cars” and was the first album Numan recorded that prominently replaced guitars with synthesizers and drum machines. Terre Thaemlitz also recorded an entire album of piano interpretations of Numan’s songs titled Replicas Rubato.

To stay with the metaphor, you’ve also changed gears: instead of running a synthesizer through guitar effects pedals to get your signature distorted synthesizer sound, you’ve switched to playing guitar directly.

I still play everything through everything. It’s still very much about creating sounds and noises. One of the fun things about making albums is trying to come up with sounds you’ve never heard before. I have no time for this analogue vs. digital argument that seems to be going on forever. I simply don’t care.

What is it you care about then when it comes to sound?

The feeling it gives you. Is the sound powerful? Is it haunting? Does it make you feel something? Can you manipulate it, turn it into a groove, a beat? I spent a huge amount of time when we were putting albums together in the early stages just making noises and recording them with my West German Uher tape recorder—you know, banging things, getting bits of concrete and hitting them with a hammer or wood or whatever it is to get different sounds. I collected hundreds, possibly even thousands of such recordings—I never really counted them.

Can you hear them on The Pleasure Principle?

No. With The Pleasure Principle we were still using synthesizers. But in anticipation of the sampler, which came out in 1981, we were doing our own sampling with tape recorders. At that time I had a studio in Shepperton where they would also make films, and I’d walk around their various metal staircases, full of interesting stuff, hitting things, banging things, scraping things—and recording everything. And then I’d take it back to the studio where I would transfer my field recordings onto quarter-inch tape and then I’d cut that, depending on what the sound was and put it through my effects pedal. I’d spend days just tweaking, doing things, exploring. Sometimes I would make loops out of it, I would cut the tape and I could work out exactly how long the tape needed to be depending on the tempo of the song. I had a little calculation that did it, if the song was ninety-six beats per minute then I knew I needed to have forty-one inches or whatever, and I would put that around the tape recorder and hang it, put little weights or empty reels on it to keep it taut so I’d have a groove from things I’d recorded out there.

Were you aware at the time of the history of musique concrète and the first experiments with tape loops and field recordings by people like Pierre Henry, Pierre Schaeffer and Eliane Radigue?

No, I wasn’t, but I wish I had known about it then. There would have been so many things I could’ve learned from.

Then again, tracks of yours like “Are ‘Friends’ Electric?” have become pioneering without that kind of background knowledge. I know some of your songs have been used in commercials. A couple of years ago that would have been considered selling out. I know lots of musicians see it differently today. Have you seen a change?

The thing that I’ve noticed about it recently is that electronic music has been around long enough to have discovered its own nostalgia, which I find uncomfortable. I’ve always thought of electronic music as being very forward looking; you could almost say that its reason for being is to search out new sounds, develop new technologies, and find new ways of doing things. Now we have people—and this is not a criticism, it’s perfectly OK—who are now coming into electronic music and referencing the seventies or the eighties as the source of what they want to do. They’re talking about old equipment with almost a romantic glint in their eye. They’d probably put a Minimoog on an altar rather than play it. I don’t have any of those romantic, nostalgic feelings about it and I find the very idea of looking backwards musically to come up with something new a really strange concept anyway. I find it particularly strange with electronic music. It goes totally against what I thought it was for. Yet we have this new generation of people who are not thinking like that, who are thinking, “I want to be doing that too! How can we emulate that?” No criticism at all, I’m perfectly happy if people want to do that. But for me…

You’ve once famously said about Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s “Welcome to the Pleasuredome” that it’s the kind of music where you want to have a sports car and just drive it faster and faster and you don’t want that song to ever end. Your biggest hit was “Cars” and I wonder if there is any connection?

Ha! I have to give you a disappointing answer: I’ve got children and I’ve got an insanely huge dog that weighs over two hundred pounds so I have this big tank of a vehicle and it’s not what I wanted. My wife Gemma got a lime green Wrangler with tiger seat covers—now, that’s a great car! I on the contrary have this horrible boring thing called a Suburban, which is far too long but with enough seats for a football team. I bought it so the children don’t fight because they fight all the time. The size of the car helps to keep them separated. We even have two TVs in it to keep them occupied. So I’m afraid my car isn’t fancy at all. It’s just to move around children and animals. When I moved to America I thought I was going to get all kinds of lovely things; I was going to get a Camaro, a Corvette, and I had all these other ideas for cars and that I was going to live the life. But here I am driving a truck.

And what car did you drive when you wrote “Cars”?

I can’t remember. But let me tell you a funny story: During the video shoot for “Cars” I remember having a casual meeting with my A&R man at WEA. He asked me which cars I liked, and I thought it was just a conversation. So I said a Corvette because I’ve always loved Corvettes. He asked what color? And I said a white one with red seats if you must know. I thought nothing of it, and then the next thing I know they’d bought me a Corvette.

With red seats?

Everything that I’d inadvertently asked for. I didn’t know that my lawyer had been seen going into CBS by somebody from WEA. They thought that after “Are ‘Friends’ Electric?” I was going to move and get a better deal from CBS. So the car was a bribe and it was given to me on the understanding that I sign a new contract with WEA for another three years.

They thought you’d do anything for a Corvette? Was it true?

Yeah. I can be bribed. Buy me a car and I’ll sign anything. This is because I have a fascination with machinery in a way that I think it’s the opposite side to my nervousness around people. I feel at ease with cars, the more powerful, the faster, the more demanding they are to operate, the better. The same goes for airplanes: the more dangerous they are, the more comfortable I feel. I don’t know if that’s my Asperger’s coming into play or not. I am so at ease in these machines, airplanes in particular, although I haven’t done that now in some time.

When was the last time you flew a plane?

A couple of years ago, but I stopped. I was an air display pilot. I would do aerobatic things at air shows all over Europe and loved it. But nearly every friend I had was killed at some time or another, which was why I stopped doing it. Since I have my own children it just seemed too dangerous a thing to do for fun. But I did love it and I miss it very much and I was so comfortable doing that in a way that I will never be around people. I think whatever that quirk personality problem I have is, it finds its yin and yang in machinery.

Joseph Beuys, who was famous for becoming a pacifist after being a Stuka dive bomber pilot in the Second World War, would always say that the planes he flew brought death but they also were beautiful. He was actually shot down but he survived and processed this experience in his art. How would you describe the impact of technology on you these days.

I’m very much at the cutting edge of technology with music. I’m Pro Tools, I’m plug-ins. The only hardware synth I’ve got is Virus, which is a phenomenal bit of a kit. I don’t have anything older than two years, I’m right up there. But if somebody said to me tomorrow the next album you’re going to make you can’t have a computer, you can’t have plug-ins, I wouldn’t really care that much because to me it’s about the sounds. So I would find another way of generating the sounds. I would go back out with my tape recorder and start kicking things again and building up sounds that way, making my loops the way I used to.

It’s interesting that you say it’s about the sound and not the song because, for instance, Martin Gore from Depeche Mode says that a song’s only a good song if you can play it on a guitar.

That’s absolutely true. From an initial production point of view, for me, we don’t even touch the computer at all, we don’t get into any plug-ins. The sound is a separate thing, it’s another day: you go out and record and build up your library that you will then work into the record, so you have a new battery of sounds for each one. In terms of actual songwriting itself, for me it’s not on a guitar—it’s a piano. Everything starts with the piano.

You’ve learned to play the piano?

I can write songs on it. I play it well enough to do that. But if you say to me play a G chord, I’ll have no idea.

Do you know Terre Thaemlitz? He has recorded a couple of piano versions of your songs.

I know one of them, yeah.

How did you like it?

I loved it. I think it’s beautiful. I wish I could play properly like that. Trent is a great piano player. Trent did a cover of one of my songs called “Metal” and he added all these piano things to it which weren’t in the original and it really makes a difference. In situations like that I realize my limitations.

You said Trent Reznor’s your neighbor. He could give you piano lessons.

I think he might be a bit busy.

Do you meet socially?

From time to time. My wife Gemma and I’ve moved to Los Angeles for just a week and Trent invited us over with the children, his baby was having a first birthday party. Robin Finck was there, Josh Homme, all kinds of people and all had their children. So you’re looking at all these rock stars being dads, which was quite surreal actually.

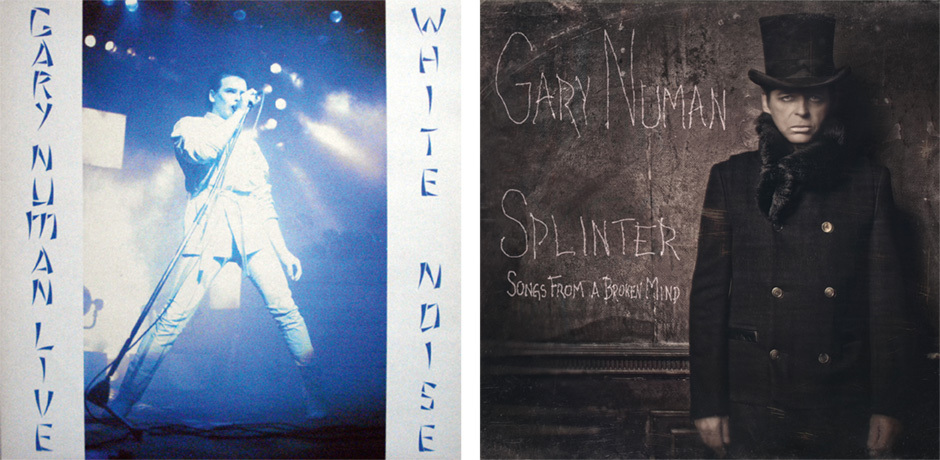

White Noise is one of numerous live albums Numan has released over the span of his more than thirty-year career. This one has the artist in top form, even displaying decidedly un-cyborgian behavior such as laughter on “Are ‘Friends’ Electric?”. Aside from Living Ornaments ’79 and ’80, it was also the only other live album that charted in the UK. In contrast, this year’s Splinter sees Numan happily bumping along a rockier road, inspired by friends and collaborators Trent Reznor and Robin Finck of Nine Inch Nails.

Somehow I find it calming to think that these people have a life outside of music.

They’re great. We’re very grateful to Trent because he introduced us to a number of people very early on that made us feel very welcome and gave us a social world. We didn’t really know anybody when we got there and almost immediately we were welcomed into Trent’s group of friends. It’s been very lovely actually, and it’s really made a difference to us.

It’s fascinating because there are people who say that L.A. is difficult to dive into. I’m not sure if they mean it socially or culturally, or both.

We’ve had no trouble. We found it more than friendly. The amount of interaction is far greater than we ever knew in England. Musicians joining in with each other, famous musicians hanging out with beginners, everybody just playing together and appearing on other people’s albums. There seems to be a joy of life there that British people don’t seem to have.

Can you explain?

I don’t know; it just seems that Americans have a very different attitude toward fun and recreational time. This is what it’s for, this is why you work, to have all this fun. One of the things you’ll notice in England if you walk around are signs that say “NO”. We went to the beach at Eastbourne and the first thing you see is this big red sign with “NO” written at the top and a long list of things you’re not allowed to do on the beach. You can’t do anything. That kind of sums up Britain. It’s the country that says NO, and they pretend it’s to do with health and safety. America doesn’t have that.

We’re living in an era when copy and paste has become the most normal working method, which could also be described as a give and take thing between artists. Would you agree? What are the social politics of copy and paste in terms of, say, sample usage?

I’d disagree. The thing about copy and pasting where you take something and you put it somewhere else is that you’re repeating something that’s already there. In contrast, when people appear on your songs as guest musicians it’s like you’re working on a song and someone will say, “I’m in town next week, we can record together.” In England they wouldn’t even think it. Robin Finck, whom I admire as one of the finest guitar players of his generation, proposed to me during a barbecue to play on a couple of my new songs, and that’s exactly what he did the following week. I never experienced that in England, not once. You’d have to sort out what they were going to get paid first. It’s not interaction—it’s work, it’s a job. In England I would have had to pay 2,000 quid for having a famous guitar player such as Robin on my record. I embrace the American attitude, and step-by-step I’m finally getting rid of my British cynicism, my suspicion, which is a positive thing. We’re really enjoying it, the climate is fantastic, and I’m amazed at how much music is going on there.

Can you recommend any new music from L.A. that we should be paying more attention to?

Fresh new music I probably couldn’t because I’ve only been hanging with Nine Inch Nails and these sort of people—established bands.

It sounds like things have come full circle in going to Los Angeles, meeting these people that you respect and who you enjoy interacting and collaborating with on your new album. Would you consider this progress?

For me it’s great. Meeting people who claim you as an influence and finding out that they’re cool and doing stuff which is really interesting and clever is something I’ve been learning a lot from. One thing feeds into the other so that it then feeds back to the beginning again. It’s very much a two-way street. I said to Trent a while back, for everything you ever got from me in terms of influence and ideas, you’ve paid me back equally, if not more so because I’ve in part also survived thanks to you. ~

Gary Numan is on tour in Europe now and plays Berlin’s Imperial Club on February 18th. This text first appeared first in Electronic Beats Magazine N° 36 (4, 2013). Read the full issue on issuu.com or in the embed below.

Published February 13, 2014. Words by Max Dax.