Flow Motion: An interview with Heatsick

The British-born, Berlin-based artist’s new album dovetails with a significant new exhibition of post-Internet art at Kassel’s Fridericianum. Lisa Blanning accompanies him there for a cross-examination. Above: Heatsick photographed by Christian Freckmann.

Steven Warwick was born and raised in England, studying fine art at university before joining forces with Luke Younger—now best known as Warwick’s PAN labelmate Helm—to form noise and drone duo Birds of Delay. Together, the pair established a firm reputation with releases on labels such as Not Not Fun and Hospital, but Warwick’s 2006 move to Berlin and his subsequent solo work as Heatsick soon eclipsed that experimental notoriety in favor of effortless, lo-fi, danceable grooves with a conceptual bent. (Birds of Delay was not forgotten—the duo return with a new album upcoming on PAN in early 2014.)

While new album RE-ENGINEERING doesn’t have quite the same Casio-fidelity of previous releases, the unquantized liquid groove—which continues to breathe in and out—remains. And although his interests have not not actually changed much over the years, RE-ENGINEERING seems to foreground certain non-musical inspirations, including contemporary philosophy and politics, with notable references to speculative realism and accelerationism. The release also coincides with a new survey of post-Internet art, Speculations on Anonymous Materials, at Fridericianum in Kassel, Germany.

While post-Internet art has been circulating in galleries and even some museums for a few years now—although it should be noted that a number of the artists involved have rejected the label in favor of “new materialism”—this particular exhibition feels significant as it’s held at the first purpose-built (in 1779) museum in Europe in the small town that hosts one of the world’s most influential art events (Documenta, which occurs once every five years). In fact, art journal Frieze Magazine ran their own survey examining post-Internet concurrently with the exhibition.

As both artist and adopted Berliner—where a number of the artists in this exhibition also live and show their work—Warwick is well-placed to comment on the exhibition. But even the most cursory glance at the exhibition materials reveals similar themes to his own, especially within contemporary philosophy. Electronic Beats travelled to Kassel with Warwick to view the exhibition, examine its themes, and discuss his own work and how it ties in with the work of the post-Internet new materialists.

Do you think you could have made Heatsick if you hadn’t moved to Berlin?

I’d still be doing something, but it wouldn’t be in the same way, for sure. It’s very speculative. But in Berlin, I was really cut off from a lot of media, so I didn’t really know what was going on. It was quite nice, in a way.

A lot of the artists in this exhibition live in Berlin, and that’s got to affect their development as well. Maybe in a different way. I had assumed that part of the reason you started making what can be termed as ‘dance music’ was because you lived in Berlin.

Partly, but making Heatsick is also equally inspired by going to a lot of art shows, which I do regularly. I have an interest in it and make art myself—I had a solo show at Kinderhook & Caracas and just had an artist book published by Motto Books. I’ve worked with artists in Berlin [such as Josephine Pryde, Sabine Reitmaier, and Jean-Michel Wicker, among others] so I’m involved in the art scene here. I remember meeting [artist duo] Aids 3d when they first moved here and we did something at Atelierhof Kreuzberg, which was a place where a lot of the artists in this exhibition also showed. I’ve seen a lot of shows by most of the artists in this exhibition in Berlin, as I like to see what’s going on.

(Everythin’ I do) I do it for you from Timur Si-Qin on Vimeo.

And it’s interesting to see their progression. I like this video by Timur Si-Qin of a bunch of dead insects floating on top what looks like a swimming pool with the sound of water running. This piece could be said to be an assemblage of objects co-existing, which is a theme that appears in [the work of the philosopher] Manuel De Landa, whose influence is definitiely in this show. Obviously, liquidity is a key concern in this exhibition—denoting physical change, political/ideological concerns, and also in the liquidity of capital floating on the stock exchange.

[In RE-ENGINEERING] I’m interested in what liquidity has come to represent, something in constant transition—in between solid, liquid, or gas—that’s expanding or compressing. There’s an extra political overtone to liquidity in that it’s a social lubricant towards accelerating a capitalistic process [a basic tenet in the philosophy of accelerationism] or even just speeding up a business deal or an interaction. You know, we want faster internet, faster business transactions. If you look at Visa itself, it’s like a passport used towards a free market concern. But I don’t really see that as an exclusively free market language; I think if you were to look at Das Kapital by Marx—he’s not the first, but one to really popularize this idea of shifting forms, congealed masses, blobs, and liquidity.

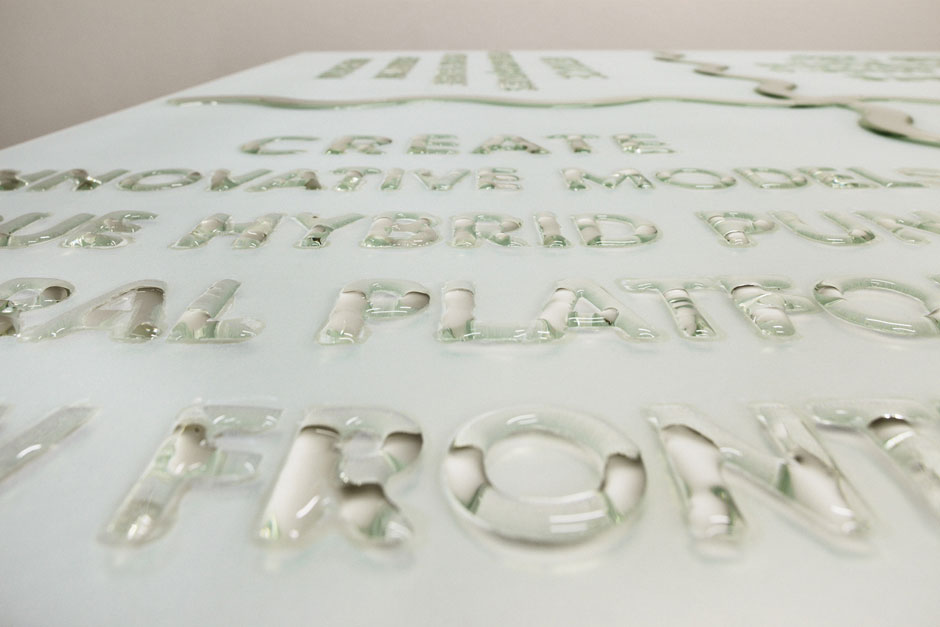

Daniel Keller’s Zion+ Platform (Blue Ocean Strategy ERRC grid), 2013. Courtesy Daniel Keller and Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler, Berlin. Installation view Fridericianum, © Photo: Achim Hatzius

But it’s the same with any of these concepts, they can be used toward whatever end. Then they become popularized and then become buzzwords. And that’s more the issue with liquidity. Daniel Keller’s pieces also reinforce this.

I like the liquidity in this work [by Keller], that it actually uses water itself, a moving, flowing form which has to be replaced. I think that it’s a lot more effective than some of the sculptures made in his earlier work [as part of Aids 3d] ABSOLUTE VITALITY. It’s capturing something in movement, which is also not necessarily fixed, which I also do in my work and LP. The corporate language is referencing business. It’s interesting to look at the ideological framework behind notions of freedom, flexibility, and liquidity used to further something that is often restrictive. Artists referencing the self as free agent could also reflect that an artist is now expected to mutlitask—providing free content and work in other ways via a prosumer style format—or in turn looking at the business flows in transactions and capital. Because let’s face it, the art market is by and large about money laundering!

When I make a reference to corporate language or the commercial, I’m interested in unlocking associations that have been generated from outside to form an emotional bond, or even further, how certain images or stimuli provoke certain neurochemical reactions in the brain. I choose buzzwords which will evoke certain historical associations or personal bonds functioning like a set of materials colliding or co-existing alongside each other, which I think is also something that is being attempted in the work in this show. Materials can co-exist, shifting the focus away from the artist.

What about your practice on the theme of liquidity?

If you listen to my record, I deliberately engineered it so these songs are not set. They’re captured but they’re subject to change, especially when played live. It is, sadly, a necessary document when you do a record, but I’m not interested in capturing or presenting an essence or a definitive finished piece. They’re deliberately a bit vague, I tried to keep them in a ‘liquid’ state as much as possible. I try to keep it relatively loose, and the tracks do flow into each other; there’s a lot of bleed. So in that sense, I try to simulate liquidity.

There’s also branding which is being played around with in this exhibition; mine’s a bit more playful, maybe—looking at the commercial language of advertising, which these artists are also doing.

Image Families by Antoine Catala at UKS from Antoine Catala on Vimeo.

That’s very apparent in Antoine Catala’s work. This is a real recurring theme, probably in contemporary art in general, but his work actually feels like advertising. When you’re drawing all of that into your art practice, are you emphasizing art as commerce?

Are you saying we can’t escape? For me, I’m looking at what’s going on today and reflecting today’s attitudes, trends, and tastes and presenting them as a manual or toolbox, as materials that you can interact and play around with. I’m interested in how the language of advertising is used to provoke an interaction or bond with the human, because it’s obviously used to consume something, and how that’s a persuasive language.

Not just to consume, but also in the sense of political propaganda. I was also thinking about how you touch on that in the first [and title] track on RE-ENGINEERING, it strings together what feels like a bunch of buzzwords.

You can consume propaganda, and in turn be consumed by it. It’s more than just buzzwords, it’s a collection of words charged with meaning and associations which recall a certain time. Whether they’re buzzwords, song lyrics, or memes, I’m interested in their affect, how we re-cognize them.

It’s funny, as well. As a device in artistic practice, humor is something that you use a lot.

I like to use humor as a device, but I’m serious about my work and it’s bringing up concerns that are prevalent today. Freud said that people tell jokes that they’re afraid of. There’s sarcasm, a lot of satire, which I would say is loaded towards something, it transports it. Something that is jokey or ironic turns it on top of its head, but it doesn’t necessarily have to go somewhere, and I think I’m more interested in sarcasm because it goes a little bit further.

I feel like a lot of this post-Internet art scene, a lot of the work feels ironic. Do you see another level to it? Is it satirical instead, maybe?

I don’t really get a satirical aspect from it, but also not everyone’s trying to be humorous. I find that sometimes there’s a flat surface and it mirrors that, but that’s not necessarily going deeper. Maybe that’s someone’s intention to mirror the flat surface—after all, Gauss said that the flat surface is a space in itself. But flat humor is another thing and it’s not a good one. Timur’s Axe piece fell short for this reason, and that it’s been remade with horizontal flows doesn’t really add much for me.

How do you get the balance right? Do you think that humor can detract from the work?

No, it can reinforce it. [Mine]’s a playful humor, but it’s not a joke. That’s a very big distinction I would draw. I was thinking recently, growing up watching all these kids TV shows I was really into, there’s this one called Round the Bend, it’s such a good title, I love it. It was super trashy and brilliant. Every single piece is a satire on an existing TV show, and it’s just for eight-year-olds. And that’s what I grew up with. And I feel like that really influenced my humor, it was just wall-to-wall piss-taking, but really funny. I was thinking more and more about a lot of British humor. It’s really loaded and quite dark, but really funny, I guess it has something to do with overpoliteness and it manifesting itself as a pressure point.

I agree. I think that the British sensibility when it comes to humor is special. I wonder if maybe part of the reason so many of the artists working in the post-Internet scene, why their take on humor falls flat so often is because it seems to be related to ironic detachment (which itself can feel very American). The ultimate message of irony seems to be, “I don’t care.”

True. I don’t want to ascribe it to a country per se; more the tendency of ironic detatchment wherever that may manifest itself. And I do care. “We care a lot,” as Faith No More once sang.

Going back to De Landa—who is a key influence for artists in this show like Timur Si-Qin and Katja Novitskova, as well as for yourself—one thing you’ve cited before as being an important idea of his for your work is self-organization. How do you think De Landa is talking about self-organizing systems?

He’s talking retroactively about how things evolve, which are usually generated via a set of so-called non-metric processes—convection, for instance—which in turn have an effect on its development. In terms of assemblage, it could be a population, how things have developed out of nothing or primordial soup. There’s one line in [De Landa’s book] The Philosophy and Simulation that I use in the track “Speculative” which goes, “Here comes the gelatinous newcomer.” For me, that was a really powerful image. I was just interested in how he was thinking about a population emerging, a city emerging, and then also emerging markets, in terms of how the world’s been forming, like 3D printing or materials—gelatinous forms solidifying, heating up, and liquefying, evaporating, and so forth.

And this is something that’s a bit crazy—sorry, I’m diverging from De Landa—but the next step is people are now viewing climate change from a business angle as being positive because then it will accelerate the trade route from Northern Europe over Russia. And that’s crazy! That’s when I thought, “liquid capital, hello!” This is one thing about De Landa, he doesn’t really talk about capitalism; he thinks it’s more complicated than that—to avoid totalities, one should think of a species as a collection of individuals. This is where my own thoughts on it diverge a little. However, I agree that it’s better to think of it as historical processes, while also treating these processes as real things which affect us and environments. I would relate the speculative stock exchange and these emerging markets in the early seventies, when the gold standard was abandoned, in terms of money being speculative. Which of course coincides with the rise of neo-liberalism, capital, and in turn processes (like financial ones, but not limited to that) becoming unfixed and floating. We are constantly living in a state of crisis and I’ve certainly grown up in this crisis. In a way, when have we never really experienced this? In that way, it’s speculative in how we’re living. That’s something which I’m interested in. I’m trying to put it in my work; it’s not always that explicit.

That statement, I think, was actually really key to this whole trip. Because this really reinforces the whole idea of “speculative” here: speculative in your work, speculative as being a key part of this exhibition. [The philosophical strand of] speculative realism becomes backgrounded. Because before the popularization of speculative realism, there was the speculative stock market. So this is a better way to understand the relation between your music, this art, and the state of affairs of the world.

But the title of the exhibition must be a nod towards the Reza Negarestani book Cyclonopedia: Complicity with Anonymous Materials. With speculative realism, I’m interested in its shift of importance away from the subject/human towards the co-existence of several organic and non-organic materials. This is functioning more as an assemblage, and it’s evident on, say, the track “Accelerationista”, where recorded bird sonority nestles alongside the text, which is itself a collection of materials evoking different associations. There’s also the song “Speculative”, where different notions of speculation are placed alongside each other.

Apropos self-organization, it’s something I’m a bit scared of—talk about self-regulating systems, of taking the human out of it. Obviously, when you take the human out of it, it’s threatening your existence, so it’s scary, but it’s also fascinating and something I want to embrace. And that’s something I also tie towards science fiction, and I’m also I’m interested in the works of J.G. Ballard, Samuel Delany, Octavia Butler.

And sci-fi is another form of speculation: speculative fiction.

Yeah, Samuel Delany predicted the Internet in his novel Stars in my Pocket Like Grains of Sand. And then we have John Rafman’s video with the nerdy, comic, sci-fi element; I did like that video.

Aleksandra Domanović’s Fatima (The future was at her fingertips), 2013 (Detail). Laser sintered PA plastic, polyurethane, Soft-Touch & metal finish, acrylic glass. Courtesy of Aleksandra Domanović, Tanya Leighton Gallery, Berlin

His and Aleksandra Domanović’s were the two most sci-fi pieces.

And I could empathize with that. Domanović’s 3D printed prosthetic arms with sensory capacity reminded me of interactive touchscreen technology; these haptic gestures. It’s a body language in a way, but it also belongs to a business.

You’re totally right. These gestures mean the same thing—they’re universal, almost like sign language—except it’s only for a touchscreen.

Yeah, and that’s patented by Apple. So each time you do a swipe, that is owned by them. Then that takes us back to Manuel De Landa, who talks about sensation and affect—things existing outside of language, if and how one can describe something. That’s why, if you do an installation, it can reach outside of language.

Give me an example of how it reaches outside of language

Well, it would be outside of our known language. So it exists as a sensation. More like, how to put into words certain feelings that are certain reactions to stimuli. And it doesn’t have to be a linguistic response, but how then to describe these things? It’s responding to an environment.

If someone says, “how do you feel about such and such” and you’re not using language, then your first thought is you’d be using pictorial or gesture/kinetic or audio or something like that. Do you mean outside of these?

More in regards to intensive qualities, like heat or olfactory sensations where it really affects you, yet that feeling might be difficult to translate. It might just be something outside of what we know. When I play an Extended Play set, people react very strongly to it, but they can’t always put it into words just what it is that they liked about it.

A still from Ryan Trecartin’s Item Falls, 2013, HD-Video 25’44’’. Courtesy of Ryan Trecartin, Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York, Sprüth Magers Berlin/London

I think [in this exhibition] the only work that truly managed to conjure that kind of immediacy was Ryan Trecatin‘s. That’s the one that truly summoned a visceral response. Like, I didn’t have a choice, it was so affecting.

Ryan Trecartin’s work is incredibly disorienting, it feels like the temporal-spatial constant compression that one encounters today, which is also refreshing as he’s such a well-known figure now.

Some of the decisions seem completely arbitrary, but it doesn’t matter because as a whole, it’s so disorienting that it really feels as though it’s a new experience. And that’s even after having watched a bunch of dumb stuff on the internet.

It just won’t give up. It makes your head feel like a overheated modem. There’s no room for contemplation.

Which of the works in the exhibition relates most directly with your work as Heatsick?

There’s aspects of interlinking in quite a few of the works here. Oliver Laric’s video had a similar tendency. Repetition is a factor I’m interested in in my work, and how that abstracts or morphs.

With Laric’s work, each character has their own set of phrases they repeat, they each say only their assigned phrases, then they interlock with each other in different ways. This actually has quite a lot to do with your music.

Yes, how loops interact with each other in different combinations to create difference.

Do you use some of the same loops in different tracks?

Yes, I’ll take patterns from different songs and sometimes put them on top of each other, almost like a remix. I do this by feeding a pattern into a looping pedal, a bit like feeding information into a computer. When I play, sometimes I get asked if I’m improvising. I don’t really view that as improvising; I view it as I’m just taking the materials and putting them in different orders, molding them in different ways.

So there’s a procedural element to your work, too?

Yeah. But I’m trying to unlock them at the same time. I’m trying to get them to play against themselves.

What I like about Laric’s piece, it’s a simple concept, but it’s executed really well.

Yeah, I would relate that to what I do, too. It’s very easy and simple and instant.

That also gives your work accessibility, which I think is a good thing. And it’s fascinating to see the different ways artists respond to all of the inspiring theory that’s driving an entire group of creatives right now.

I think we live in an interesting time right now. Boundaries are becoming more fluid. ~

Heatsick’s RE-ENGINEERING is out now via PAN; his Berlin album launch party takes place on December 5th at Südblock. Speculations on Anonymous Materials is open until January 26, 2014, at Fridericianum in Kassel, Germany.

Published November 27, 2013. Words by Lisa Blanning.