“I’m probably not curious enough”: Hans-Joachim Roedelius talks to Asmus Tietchens

In this interview taken from the Spring 2013 issue of Electronic Beats Magazine, the krautrock legend and the electronic avant-gardist discuss their influences, work and the necessity—or not—of iPhones.

In 1967, Hans-Joachim Roedelius helped co-found the Zodiac Free Arts Lab in West Berlin—an open performance space for sonic experimentation and against “bourgeois” musical conventions. Despite its brief existence, the Lab served as a catalyst for one of the most influential and decidedly European musical movements of the twentieth century, namely krautrock and kosmische Musik. Since then, Roedelius has evolved into one of the genre’s most prolific figures, his exploratory electronics with Cluster and Harmonia becoming a source of inspiration for aesthetic cherry pickers David Bowie and Brian Eno—not to mention those keeping the flame of the Zodiac spirit alight, like German electronic avant-gardist Asmus Tietchens. Roedelius and Tietchens recently met up in Hamburg to discuss the relative merits of Germany’s musical exports for the Spring issue of Electronic Beats Magazine. Furthermore, ElectronicBeats.net is hosting an exclusive album stream of Tiden, the second album from Roedelius’ collaborative project with Stefan Schneider—mentioned in the interview below—here. Main photo by Margret Links.

Asmus Tietchens: Welcome, Joachim, to my world. This is Okko Bekker’s studio. Here I’ve worked, secluded from the world, for more than two decades now. And I should mention that Kluster with Conrad Schnitzler was encouraging for people like me. That goes for the recordings and live shows.

Hans-Joachim Roedelius: You must have released at least a hundred records since then.

AT: I’ve stopped counting. I release music regularly, but I don’t see the point in it anymore. I mean, I love to produce music day and night. But to release it? I am fully aware of the fact that I do music for a really small minority of listeners. If one day nobody is interested anymore in my music, I won’t care less. At least I will still listen to it.

HJR: The funny thing is that the experimental music Cluster has done in the past is now seen as being somehow mainstream. I’d say more people than ever are listening to our music and consider it a kind of pop.

AT: Indeed, I wouldn’t call my music experimental anymore. When I make music, I know beforehand how it will sound in the end. That’s not really experimental. On the other hand, when I listen to certain minimal techno or dubstep releases, I’m sometimes completely stunned by the radical approach these young musicians show. It’s my students who continue to confront me with musicians work by Ricardo Villalobos, Alva Noto, Wolfgang Voigt or Richie Hawtin. In this kind of music everything is about details. If you start to listen carefully, you can become addicted to their skills and how they breathe life into minimalist concepts. I am talking about complex tracks that are very carefully composed. But I admit that I’d never found out about them myself. It’s always my students who confront me with advanced contemporary music.

HJR: Do you dance to music?

AT: No, I don’t. I can’t and I don’t want to. I prefer to listen to music. Carefully. Focused. A friend of mine recently sold his Roland TR-808 on eBay for 2,800 euros. It was an original from 1981. I was quite impressed by the winning bid and I understood that these people who work in the minimalist electronic field really know what they are doing—and that they are willing to pay the price.

HJR: When I turn on the machinery, I never know in advance what will happen musically. On the other hand, I work hermetically, within my own world. I don’t listen to contemporary music. Sometimes I do at festivals, when I am part of the booking. But otherwise…

AT: But you continue to work with young people, don’t you?

HJR: I’m just coming from a session with Stefan Schneider of To Rococo Rot. With him I never know where the music will lead us. Whenever we work together there is creative tension in the room.

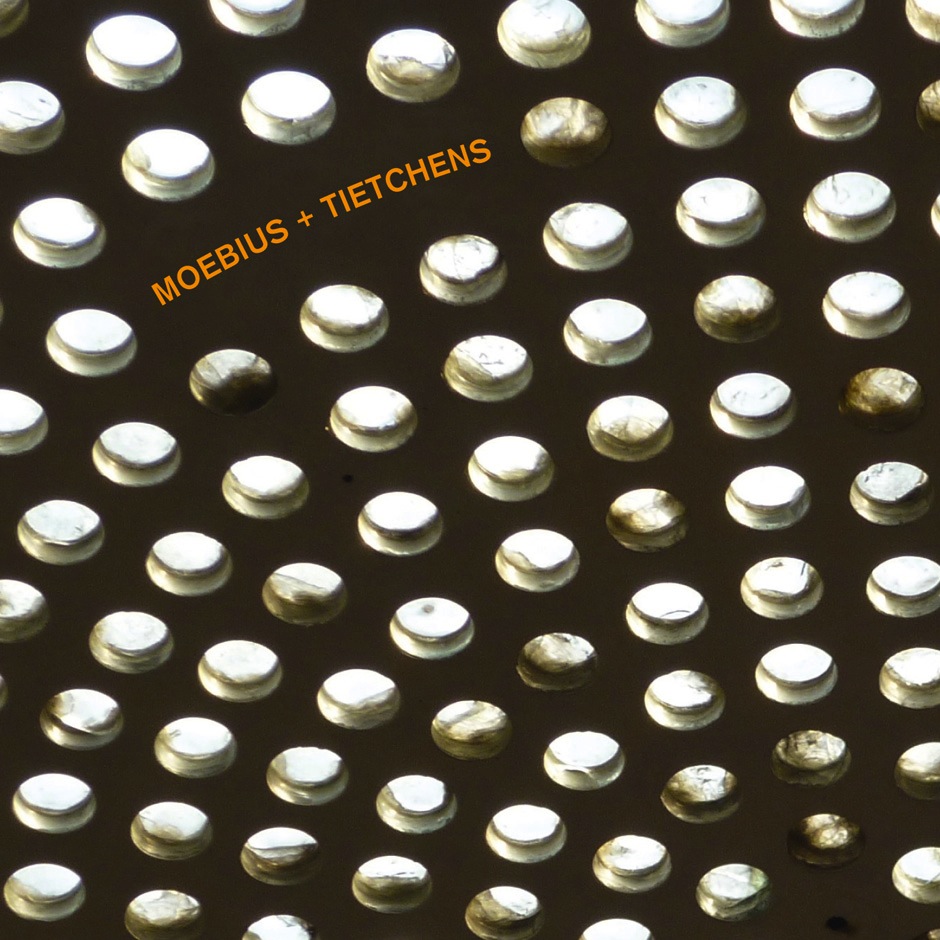

Above: Tietchens’ most recent release is a 2012 collaboration with former Cluster and Harmonia member Dieter Moebius, aptly titled Moebius and Tietchens. The pair last recorded together in 1976 for Moebius’ project Lilienthal featuring (amongst others) the legendary Conny Plank on vocals, guitar and synthesizer.

AT: In Hamburg recently a new club opened. It is called Golem, and you’ll find it near the fish market. I had an appointment there with someone and we were having a cup of coffee. During the whole time of our stay, we listened to music by Harmonia. I asked my friend if he’d like to guess when the music was originally recorded. He answered, “Two, maybe three years ago?”

HJR: That’s interesting. Michael Rother and I started Harmonia in 1971. And the album we did together with Brian Eno was recorded in 1976.

AT: I honestly like what I see as a new openness when it comes to listening habits. Twenty years ago, in Hamburg you had to explicitly go to the Atonal Bar to hear avant-garde stuff. Suffice to say, the Atonal Bar only opened on certain days and it only attracted a certain kind of people. I couldn’t recall exactly when it started, but I have the impression that the world has become so much more open.

HJR: I think in that regard the ’80s were important. That was a challenging decade when it came to experimental music. And the next big breakthrough, of course, was the internet with its file sharing possibilities, which has enabled millions of people to listen to new and avant-garde music.

AT: Well, since every single recording of mine is downloadable for free via the internet now, I couldn’t live from my music alone. In that regard, the internet wasn’t a blessing for me. My gigs and my lectureship in sound design at the University of Fine Arts in Hamburg bring in all the money.

HJR: How many students do you have?

AT: This year it’s 24. They are all between age 22 and 28. I always like the afternoons I spend with them at the academy. We basically talk. It’s not me telling them stuff; it’s us talking together. I basically moderate the conversations of my students when they talk about their own music. Joseph Beuys worked that way, too.

HJR: I never had any teachers. But ancestors of mine were church musicians. It’s likely that I have it in my blood. But my path went from noise to sonority. At the present moment, I prefer to play the piano than to experiment with noisy electronics.

AT: That’s interesting. I think one of the reasons why Cluster started making noise and having an audience was also due to Joseph Beuys and John Cage. They both preached the so-called “expanded concept of art”. Cage expanded the concept of music ad infinitum. Funny enough, I only learned that I owed everything to Cage after I already practiced his teachings for a couple of years, not knowing that he had paved the road for people like me.

HJR: How did you find out?

AT: German night radio. That’s when I started to listen to these obscure shows. Because I was starting to attend German secondary school, I thought I had to listen to strange music that I couldn’t understand. I imagined it was an integral part of growing up and that I had to endure this to become an adult. But pretty soon I started to embrace and love the music I heard. I would hide under the blanket, pressing the radio to my ear because my parents weren’t supposed to find out. In total darkness I heard Stockhausen or tape music by Pierre Schaeffer or Eliane Radigue, things played backwards or at double speed. I heard it on the radio, so it had to be music. Of course, this then allowed me to play my own tapes backwards at any speed I liked and to experiment with my tape machine.

HJR: You owned a valuable tape machine as a teenager? How come? How old were you?

AT: I started listening to radio at night when I was maybe 12. Then I begged my parents to buy me a tape machine. And I finally got one for my 15th birthday. But I didn’t realize that I actually owed Beuys, Cage, Sala and Schaeffer respect.

HJR: I was always focused on myself. I had so much to do that I simply didn’t have any time to study. I always did everything the way I thought it should be done. I never doubted my decisions. I would stay up all night, working on new tracks, when the rest of the band members were already sleeping. It was that way with Cluster and it was the same with Harmonia.

Asmus Tietchens photographed by Margret Links

AT: What’s your relationship to Karlheinz Stockhausen?

HJR: I once attended a lecture of his in Cologne. This must have been around 1969. He entered the auditorium and then locked the door. The students were forced to stay until he’d finished his lecture. I was shocked. I actually hated him for that attitude. But I regret that I didn’t dig deeper into his music for that very reason. I’d listen to his music, but it wouldn’t touch me. I might be walking on thin ice, but I felt that his music was too thought through. And I know that Conny Plank and Holger Czukay had a much better opinion of him.

AT: I never met Stockhausen personally, but of course I know that he mainly wrote serial music and only a tiny bit of his oeuvre consisted of electronic compositions. I started to listen to Stockhausen when I was twelve years old. His “Gesang der Jünglinge” [“Song of the Youths”] was probably my favorite composition back then because it combined singing voices and electronic soundscapes—back in 1955! I was especially blown away by the fact that he had composed his music with audio tape. Stockhausen was absolutely important for the cultural development of post-war Germany. He is famous for claiming that after twelve years of fascism, after Hiroshima and the death camps, music shouldn’t be allowed to be emotional anymore. He wanted a new, objective music that could not be misused by whatever dictatorship. In a way, he said the same thing Adorno did when he claimed that poetry wasn’t possible anymore after Auschwitz.

HJR: Well, I still don’t like him. But I can of course see that his thoughts on serial music opened doors for an entire new generation of electronic musicians. I mean, all the legions of contemporary electronic musicians reference Stockhausen and Schaeffer whether they know it or not.

AT: What I didn’t know at that time though was the fact that Stockhausen was an arch Catholic until around the time he wrote “Sirius”. But you have to really listen to the lyrics to grasp the fact that the boys in his “Gesang der Jünglinge” are praising the Lord. I once read Texte zur Musik [“Texts on Music”], a very interesting book that he had written in 1952 about his aesthetics, his aims and his concepts in the light of his “worldview”. I became a loyal follower of his music, but it ended abruptly with the release of “Sirius”. I couldn’t understand him anymore. To make a long story short: this music was played on the radio, and I think it was a great thing… when it still existed.

HJR: I never understood how they could tolerate the radio going so down hill. Nowadays everything has become so commercial. A listening “career” like yours that was based on radio wouldn’t be possible anymore. In Austrian national radio they probably play exactly one song a year from me. I can see this from the royalty statements.

AT: I don’t listen to radio anymore. At home, I enjoy the silence. And in the studio it’s the same. There are no windows facing the street. I work in total isolation from the outside world. I love tranquility. I love to walk in the woods surrounding Hamburg. I enjoy the fresh air and, to a slightly lesser extent, the experience of nature. I wouldn’t call it inspiring or whatsoever. I also don’t take drugs for instance or use iPhones to enhance or photograph such moments.

HJR: You never took any drugs?

AT: No, never. I smoke cigarettes and I drink coffee. I’m probably not curious enough.

HJR: A Swiss magazine recently asked me which objects I am always carrying with me. I answered: my wedding ring and my iPhone. I lost my wedding ring in the Tyrrenian Sea in the meantime, during my holidays in Corsica.

AT: I own an old Nokia phone from the mid nineties. Students of mine have offered me respectable amounts of money to buy it from me and impress the others with a vintage phone. But I like it because it is still functioning. I once got it from my brother when our mother was on her deathbed. He wanted me to be reachable. Our mother died, but I kept the phone. I only turn it on occasionally. There exist only six people in the world who have my number.

HJR: I am constantly reachable and I couldn’t imagine it otherwise.

AT: I hate it when you are in conversation with someone and then the cellphone rings. Instead of turning the incoming call down most people would answer the phone.

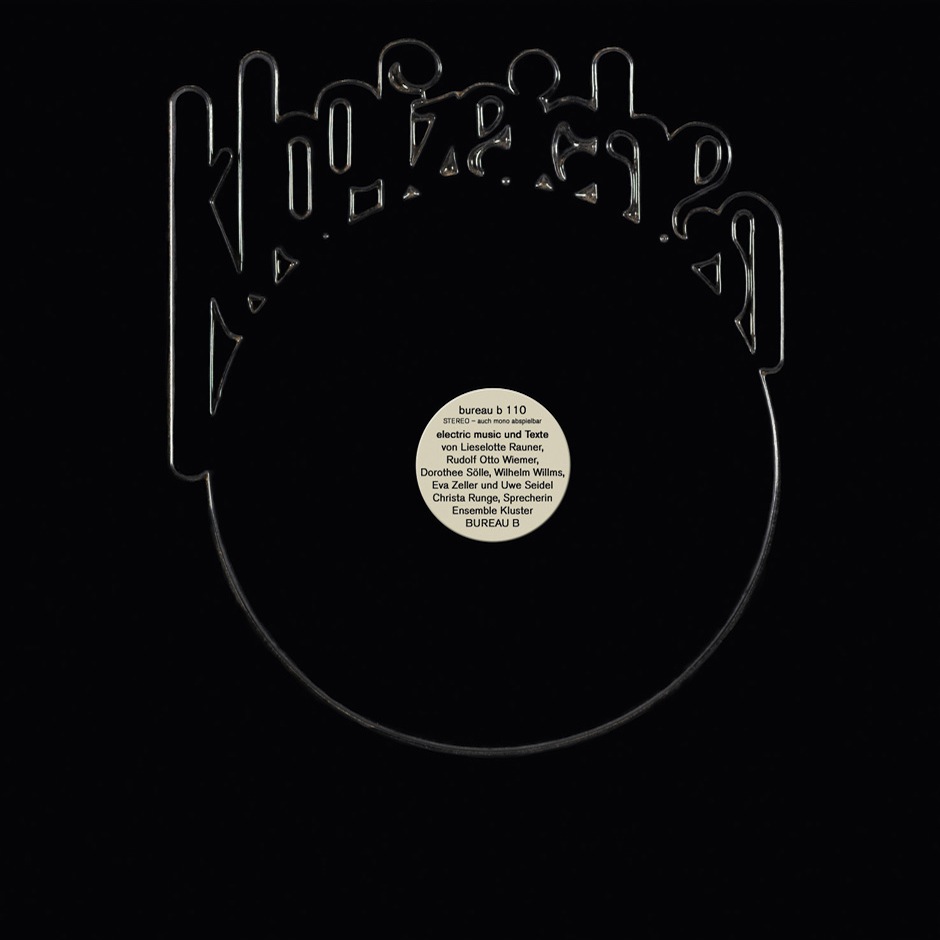

Above: Roedelius, Conrad Schnitzler and Dieter Moebius put out their first album as Kluster in 1970, the recently reissued Klopfzeichen (Bureau B). Shortly thereafter, Schnitzler would leave to pursue a solo career while Moebius and Roedelius changed the band name to the more anglicized Cluster. As a duo, the two would make some of the most beautiful minimal electronic albums of the seventies, including the classic Zuckerzeit and Cluster 2. Since 2010, Roedelius has continued the project as Qluster with sound artist Onnen Bock, putting out a whopping four LPs, including 2013’s Lauschen.

HJR: Do you still buy records?

AT: Every now and then. I live in a very small flat, so I have to carefully pick my purchases. I recently bought Francisco López’ Untitled album. I also bought a record by Norbert Möslang, who uses self-made instruments—toy sounds, closed circuits, stuff like that. And I bought a CD by Carsten Nicolai to complete my Aleph collection. You actually should pay a visit to Freiheit & Roosen on Große Freiheit and Paul-Roosen-Straße here in Hamburg. This is a great record store that is specialized in German experimental music, amongst other things.

HJR: They sell all the original vinyl?

AT: Exactly. The owner is a maniac, but in the positive meaning of the word. He sells all the original records from the ’60s and ’70s. But he also knows what they are worth…

HJR: Maybe I’ll go there next time. Did I ever tell you that someone stole my only vinyl copy of the first Cluster album? I have to check the store; maybe they’ll have it.

AT: Bowie loved Cluster—maybe he should check the store out too.

HJR: I will never forget Bowie’s appearance on the German TV show Wetten, dass..? He famously asked the audience: “Do any of you know Harmonia?” Of course then there was this uncomfortable moment of total silence, as nobody knew Harmonia.

AT: Did you ever see your influence in his work?

HJR: All I know is that Brian Eno played our music occasionally to him and to other people he hung out or worked with, such as Bryan Ferry or U2. But since I almost never listened to U2, I couldn’t tell if they’d been inspired by us.

AT: Almost?

HJR: I once saw them in a stadium by invitation. But I left the place after a couple of songs as it was simply too loud for me. I then wrote a letter to The Edge, complaining about the volume, but he never answered. Honestly, I don’t understand why concerts nowadays have to be so loud.

AT: Apropos loud, I once hung out for an afternoon with Carsten Nicolai and Ryoji Ikeda.

HJR: Carsten Nicolai can be insanely loud, indeed. It’s this digital noise that, when played at very high volume, can make you deaf.

AT: I accompanied them to their soundcheck. I asked Carsten if they could play for me the first part of the concert as I couldn’t attend their show in the evening. And I asked him if he could give me a sign, like, ten seconds before it will get really loud—so that I could leave the venue in time. Which he did. I left and could only imagine how they basically shattered the building with their high frequency sound and their peaked impulses. I wouldn’t have enjoyed it. Don’t get me wrong: He does beautiful, poetic music. But it’s just too loud for me.

AT: The iconic German noise music pioneer Uli Rehberg recently said: “We have to torture the people with silence.” He’s probably right.

HJR: That’s interesting. I played a very quiet concert in David Lynch’s Silencio club in Paris with Charlie Chaplin’s son Christopher recently.

AT: Do you know Richard Chartier? He works in the area of reductionist microsound electronic music—specifically on extreme texture in very quiet, very sparse musical set-ups. I like him a lot. Funny enough, even the typography on his cover art has become micro, almost unreadable! It’s only four point or even less. You could probably say that Richard Chartier and the other reductionists are making music for the very young: those who can still see and hear.

HJR: How are your live performances nowadays?

AT: Not loud, for sure. And I don’t do anything on stage. I monitor the correct playback of the sound files. Actually, I always offer to just send the sound files, to instruct someone how to set them up and to stay at home. But they never draw this option. They always want me present as a living statue.

HJR: That’s how Conrad Schnitzler used to give concerts.

AT: Yeah. As the stuffed dummy I guess I’m supposed to add authority or authenticity to the fact that my listening concerts are nothing more than me pressing the play button. It’s as if the bookers are afraid…

HJR: It could also be that they are just happy to have you there. It could be a sign of respect too. Conrad Schnitzler used to send Wolfgang Seidel, his main confidant, to perform on his behalf with a suitcase filled with cassettes.

AT: Well, I don’t like to travel. I prefer to work in my studio. Though I was in Iceland recently. The emptiness really impressed me.

HJR: Were you in Reykjavik?

AT: No, actually I found myself hundreds of kilometers northeast in Seyðisfjörður, a modern city with maybe 600 inhabitants, surrounded by tall snowy mountains and emptiness. It was nice, but honestly, I don’t see the need to travel at all. If you live in a big city like Hamburg, good things will happen there anyways. I will never forget the day when they announced a live performance of Stockhausen’s “Gesang der Jünglinge” at the Musikhalle with Stockhausen as a conductor. I immediately bought a ticket. A couple of days before the concert, Stockhausen had held his infamous speech about the terror attacks on September 11. He basically claimed the attacks to be the biggest work of art in the history of mankind. You remember the shitstorm he kicked off with that press conference? Undoubtedly, it was a very emotional time. As a result he then cancelled the concert, as the audience probably would have lynched him. And when they rescheduled the concert, I wasn’t there—I was traveling! ~

Published June 23, 2013.