How Outernational Festival Fights Prejudice With Marginalized Music

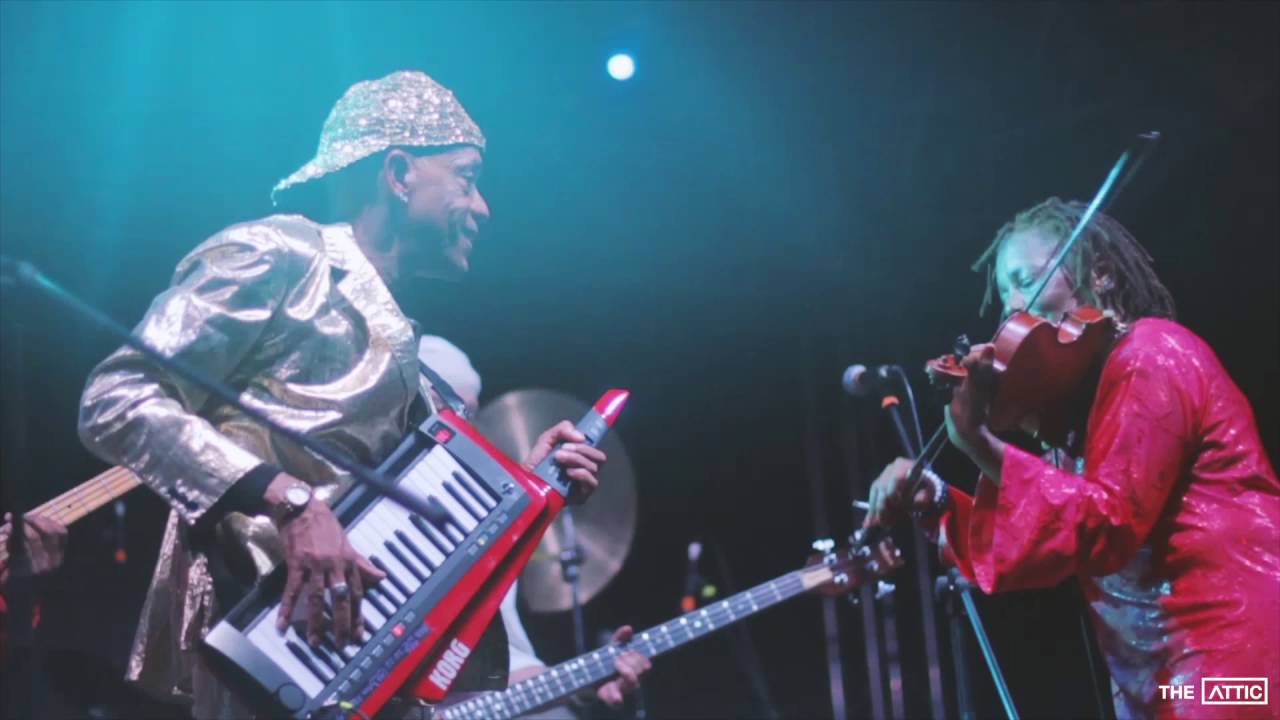

I started Outernational Days festival while working as an event promoter and resident DJ at Control Club in Bucharest. Around that time, my brother and I launched an online music magazine called The Attic with the main purpose of questioning all music, trying to understand it with an open mind and acting responsibly with the related cultural products. In 2015, while I was working at Control, I was commissioned to make a series of live concerts with bands from all over the world that encompass a contemporary sound specific to their home region. I was aware and skeptical of the so-called “world music” bands and looked instead for those who would take the “world music” spirit and sound into the future with an eye for experimentation. For the end of the season, we booked two bands to perform on the same weekend, and I knew that I wanted to make something bigger out of it—but I wasn’t sure exactly what.

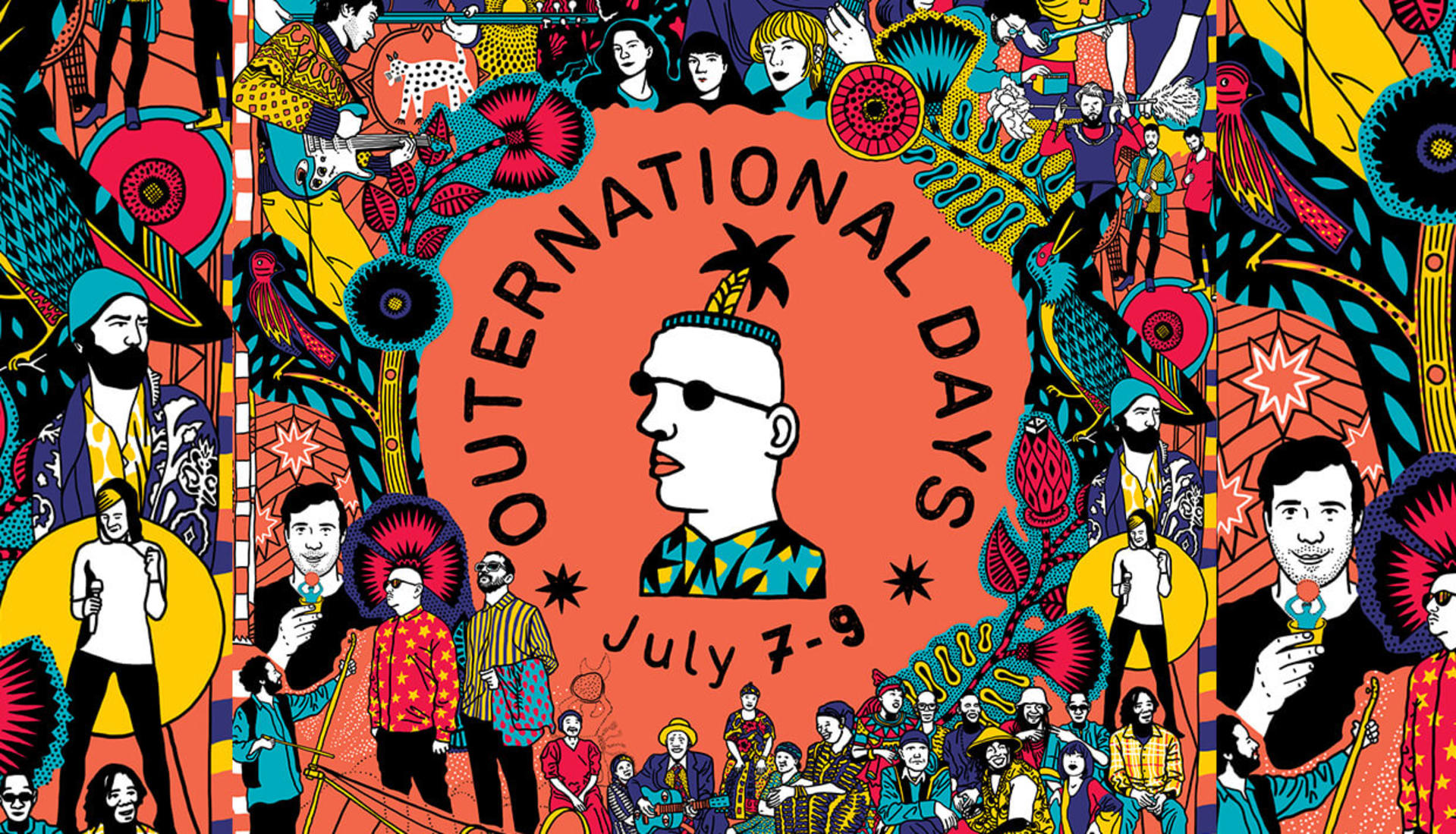

At the same time, the Romanian Ministry Of Culture hosted a contest for the funding of cultural projects, so I connected the two opportunities and started to imagine transforming that weekend into a mini-festival. My initial idea was to make a multicultural festival of culturally rich, diverse music from areas that aren’t explored enough—or even at all. Besides concerts and DJ sets, the festival would include a panel discussion around the “outernational condition,” lectures and a percussion workshop led by the legendary Turkish percussionist Okay Temiz.

We ended up losing the contest, but by that time I had already advanced with so many bookings that I just couldn’t stop. I decided to take a financial risk and continued to organize the first Outernational festival without the funding—which I actually won the following year and used to help finance Outernational Days 2. The first edition highlighted musicians who have been active since the 1960s to contextualize outernational music throughout the past six decades or so. This year the focus is on contemporary acts with lectures and panel discussions about the circulation of cultural and artistic products. We want to create a unique space in our main daytime venue, the Uranus garden, which captures the true essence of the outernational condition and urban space in Bucharest: a relaxed, cool atmosphere created in the heart of chaos and unrest.

I first found the term “outernational” several years ago in a piece written by Ion Dumitrescu that explains the “outernational condition” and its means of production, distribution and consumption. The term doesn’t exclusively define a genre or a musical aspect, but rather an emerging cultural movement that investigates the perpetual transformations in music and pierces the geo-political spaces where they were produced. It’s been used on various occasions to describe a sound or culture from an “outer” domain, a place somewhere outside history that evokes a shapeless world located at the periphery of the international scene. On the one hand, “outernational” may refer to various non-Western folk traditions, but on the other hand, I believe it can also reflect an entire human condition. So for instance, contemporary artists such as Traxx, Detlef Weinrich (aka Toulouse Low Trax), Vladimir Ivkovic or Mark Ernestus are geographically located in the West, but their approach to non-Western cultures suggests that they could be from anywhere.

Outernational music comprises many contemporary hybrids from all over the world, from Kurdish halay to Bulgarian chalga orchestras, Peruvian chicha, Palestinian dabke, Mexican narcocorrido, Egyptian electro-chabi and Romanian manele, among other styles. None of them gets very much, if any, exposure in mainstream media. Manele, for instance, is usually associated with mafia bosses, with the lowest class of society, with the Roma communities that have been marginalized for centuries, with thieves, with poverty. This music and culture doesn’t interfere with the aspiring white Western citizen, which is an identity many Romanians wanted to achieve after the fall of the Communist regime.

Romania is a melting pot of Eastern and Western cultures, but in the last two decades the Ottoman influence has started to pale. Instead, people wanted to be evolved, Western, white Europeans who are politically correct, ultra-modernized and who wish to have nothing to do with Eastern traditions and values. For some of them, I think manele can be a sort of nightmare. Manele musicians have been omnipresent in the Romanian soundscape, but because of racial biases and its association with lower classes, they have been looked down upon and barely involved with other acts in the mainstream media. Manele is never aired on radio and only a few TV stations have embraced it at certain times in a tabloid way. Although there are hundreds of manele artists, they all operate through two or three agents, and the process of recording and production is limited to very few studios.

Meanwhile, “rominimal” artists are highly appreciated on the European electronic music scene. Rominimal is a pseudo sub-genre of techno and house that evolved in post-Communist Romania, where every Western influence was an aspirational model for the younger generation. Rominimal never interferes with outernational—except in some particular and curious cases like Ricardo Villalobos, who heavily influenced Romanian DJs but also, for instance, played an Omar Souleyman track at the rominimal festival Sunwaves a few years ago. Furthermore, rominimal artists and their fans often express vehement criticisms of manele. Outernational music lies at the margins of this powerful exchange between Western influences and Romanian music. It creates subversive channels of communications and pierces disputed places and neglected territories. It is the consequence of marginalization but also the root of its uncompromising nature. In this process, the limits of perception are challenged, breaking down social and cultural borders.

Manele has therefore been a crucial part of Outernational’s program; last year we booked the legendary Dan Armeanca, and this year’s headliner is the most iconic contemporary manele singer, Florin Salam. He is an extraordinary performer and part of what we stand for. When we booked him we had a long conversation with him to explain who we are, what we’ve done so far and what we’re trying to do next. He was very open-minded and happy that someone “from another world” wanted to do a project with him. I don’t know if he’s fully aware of what Outernational Days represents, but he seems to trust us and is excited about sharing the stage with other foreign artists. We’re putting him on a bill with acts from countries like Niger, Kenya, Senegal, Lebanon and Turkey in order to hopefully create a space for shifts in perception. This year’s discourse program includes a panel discussion called Manele In Romania: From Cultural Paradox To Social Meaning, which will include Romanian and American musicologists, Romanian musicians, journalists and a booking agent and promoter for many manele artists.

There used to be endless Facebook arguments from Romanians whenever a manele singer was booked in an unconventional venue or context, but this time the response that I’ve seen so far was very enthusiastic. But no Romanian corporate sponsors or institutions were willing to “risk” their image on an association with a festival that presents manele on its program. We have this inside joke that when we have to deal with a racist person or context, we don’t use the word “manele”; we call it “contemporary gypsy music.” Its bad reputation has snowballed over the last two decades, but the music itself has never been judged in terms of aesthetics. Nobody distinguishes between “good” and “bad” manele; they just hate it all without even giving it a single chance. You don’t have to like it, of course. But don’t hate it just because it reflects the realities from your own country that you neglect and don’t want to know about.

Outernational Days fights prejudices, vices and fears like that one. It includes artists from all over the world and doesn’t fetishize one region or hemisphere. So for us, booking Florin Salam is not some kind of “kitschy gimmick” that we would need to explain to our audience, which is very mixed and diverse and consists of both Western and non-Western groups of people. Even if Romania is geographically located in the West, I don’t think it can be considered Western the way a country like Germany is.

Many musicians, music enthusiasts and record labels have in the past decades become interested in resurfacing forgotten music. While I’m aware of the colonialist history of some such investigations and that one could view them as fetishizations of the other, I see them as attempts to understand the other—to “de-otherize.” After all, Western “orientalist” studies of Eastern cultures have evolved since the 20th century, namely in that the research methods no longer rely solely on the writings of chosen Western explorers. Technology and internet has setup a new form of neo-colonialism, but if used as an effective research tool, it can produce the opposite effect. It can get you in touch with ideas and people that will question everything you thought you knew. This wave in interest in those “other” cultures creates the perfect climate in which Outernational Days festival can evolve.

We should not disregard our history, but try to preserve it in a way that would give us a general idea of what something like a “national cultural identity” could mean. As a festival we have to be conscious about the realities of the world. We need to be as good as we can be and try not to fall into the same old traps or repeat the same old loops and mistakes like our predecessors. Instead we should contribute to a change of perspective and of practice; we have to be responsible for the cultural products we consume.

Outernational Days Festival takes place July 7-9 in Bucharest, Romania. Find more information here.

Published June 30, 2017.