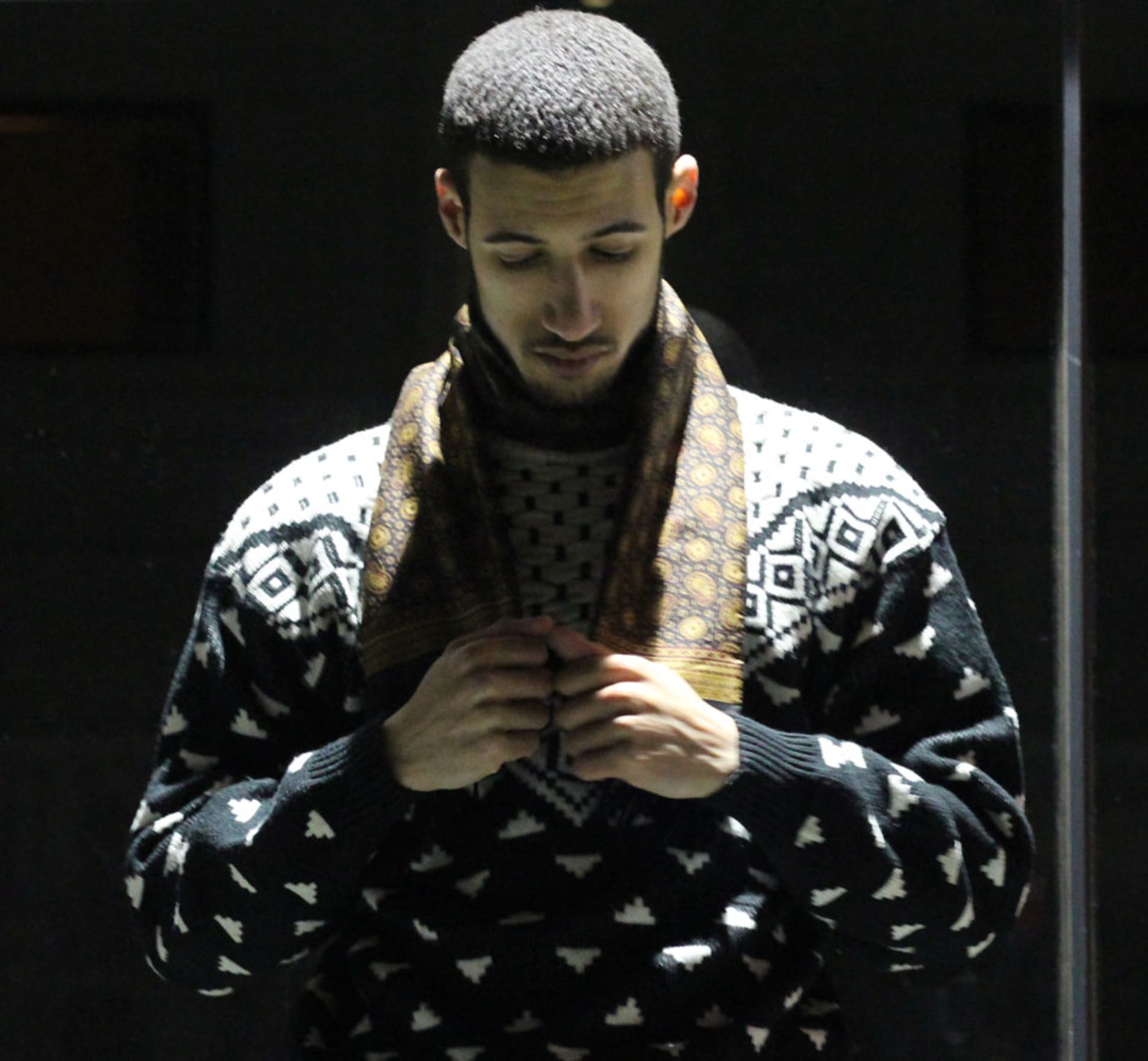

Revisionary: An interview with Visionist

Angus Finlayson speaks with the young British producer re-imagining the possibilities of grime into something that transcends its highly localized origins.

Visionist is Louis Carnell, a producer born in South London, though he spent a good portion of his teenage years in Nottingham. Carnell cut his teeth as a grime MC; his career as a producer took off after he moved back to London for university. These days he’s often cited as one of the bright young talents emerging from the Keysound label, alongside Beneath and Wen. But as Carnell is quick to point out, he’s not quite as fresh-faced as his contemporaries, having made his name with crisp, UK funky-indebted drum machine work-outs as far back as 2011.

Carnell’s music, a fluid hybrid of garage, UK funky, and dubstep, but with grime at its core, also finds kindred spirits beyond Keysound. He is heavily engaged with the recent resurgence in instrumental grime in the UK, having championed new artists such as Bloom and Filter Dread through his own Lost Codes imprint. More unusually for a UK artist, Carnell seems to be gaining traction in the US. Last month, he put together an excellent mix for New York’s DIS Magazine, a publication better known for championing the decidedly internet-ty aesthetic of US labels like UNO NYC and Hippos In Tanks. His recent self-released Crying Angels EP makes the link more explicit, picking up where NY producer Fatima Al Qadiri’s Desert Strike EP left off in its weightless re-imaginings of grime classics.

This kinship is the product of a trip Carnell made to New York last year, after feeling stifled by associations with young techno producers in the UK. It’s one that will be cemented further by a forthcoming EP for the Lit City Trax label, best known for releasing DJ Rashad’s landmark footwork LP Teklife Volume I: Welcome To The Chi. As Visionist’s musical identity becomes ever more transatlantic, Electronic Beats caught up with him to discuss the return of grime, the unfortunate ubiquity of the Wiley drumkit, and discovering like minds across the pond.

So I understand you were an MC before you were a producer?

Yeah, when I was about 14, 15. I was in Nottingham at the time. Grime was kind of different [in Nottingham]—the sound was a bit different from London producers. But I used to listen to a lot of London producers.

When you started producing your own tracks, were you making fairly straight grime?

Pretty much, a lot of very basic grime. I didn’t really know what I was doing, just what tempo to do it at. Then I started making more kinda ambient grime. I used to sample Indian vocals a lot. It was all 140 [bpm] and you could MC to it, but it got dark quite quickly.

I guess it wasn’t really designed to go off in a club?

Nah, it wasn’t really club grime at all. At that time I was more interested in Dot Rotten, people like that, more than the hype MCs. I was more interested in the people chatting deeper lyrics. That’s the way I was MCing as well.

The first couple of records you put out, they had more of a house influence.

Yeah a little bit. [Before that] I did the whole funky house thing, for a very short period. I made this remix with a mate, had it played in a couple of student clubs in Soho [laughs]. But I got bored of that quite quickly. I was always into Burial, all that kind of stuff, and I went to see Pearson Sound and Pangea do a talk. They played early James Blake and Untold, early Pearson Sound—“Wad”, I think it was. I was really intrigued by that, and I started researching those kind of artists. Then I went to see Addison [Groove] play, but didn’t know he was Headhunter. I liked dubstep and went to dubstep [nights], but I didn’t really [produce] it. When I heard “Footcrab”, that was something pretty new. But even when I heard footwork I thought, “This is raw, so it’s kind of like grime.” I’ve always had love for grime, and because I was producing it for so long, I think it just comes naturally for something [I make] to be linked back to it.

You made this track with Beneath and Wen, “New Wave” [from the Keysound Allstars compilation], and you guys are often mentioned in the same breath. Do you think you three are coming from a very similar place, musically?

Nah. That was my idea, to do the “New Wave” track. We were all doing that Rinse show together, so I thought it’d be a nice idea to do a three-way collaboration. Obviously, I did call it “New Wave”, but I was actually coming up a year before them. I had about four or five releases before they’d done anything. Also I feel like—with Beneath, his thing was funky-dubstep. With Wen, obviously it’s more grime, but again I feel it’s more rooted in dubstep. I don’t feel like my sound is rooted in dubstep. But we still play each other’s tunes, we’ve got mad respect for each other’s tunes.

I wanted to talk about this “Pulse X” remix record you contributed to. It seemed like a statement—here are some of grime’s new generation reinterpreting a classic. Why do you think there’s been this resurgence in instrumental grime lately?

It seems people are either going towards techno or towards grime at the moment. Certain people obviously want something a bit more rooted to the UK. And with dubstep being so commercialized… grime wasn’t really commercialized. Grime MCs went and got commercial, but Tinie Tempah and all them, they didn’t get big spitting on a grime tune, they got big spitting [with] Labrinth. But dubstep was commercial as dubstep.

So with grime, there was still something to come back to after it got big?

Yeah. Though grime’s been getting mixed up with trap a lot recently. I love trap, but when someone starts saying something’s a grime tune when it’s obviously a trap tune… And the big guys have started confusing people—like Jammer, when he met Wacka Flocka Flame and showed him that Footsie tune which is a blatant trap tune, but called it grime.

With your label Lost Codes, you said one of your aims was to persuade some people who’d started making rap to come back to grime. Is this something that bothers you—that some UK producers have started taking influence more from the US?

It’s not that it’s influenced by the US, I don’t care about that. It’s more… with grime, it’s been disregarded so much. People forget how creative it actually was. But in a lot of music I hear now, I feel like that whole spirit is kind of lost. It becomes a bit more generic. I think that’s what I’ve got a problem with—it becoming generic—rather than influence. I went to New York last year, which is why I’m doing a Lit City record. Nguzunguzu and Fatima [Al Qadiri] and all that lot, they love grime. And if you listen to the tunes they’re coming with now, they’re very linked to grime but in their own style, and they’re doing it really well.

How long did you spend in New York? What did you get up to there?

I spent two weeks in New York and managed to get myself a couple of shows playing for On The Sly, Lit City Trax and East Village Radio. The main guy I hooked up with was [Lit City co-founder] J-Cush. Through him, I met Rashad, Fatima Al Qadiri and played alongside Kode9 and Total Freedom. I was told by a friend who runs a very good label in New York that people would like my music out there, and I’m very glad I took his advice.

I went over to New York with this idea of… I was being put with all the up and coming techno producers [in the UK], because I made tunes like “Circles”. But I didn’t really get it. They were making much more techno techno, I was too different. So I was like, “I’m going to take this right back, focus more on vocals.” Through all my music I’ve loved writing with vocals. So I went to New York with this plan, started writing some stuff, came back and wrote a whole load of stuff. There’s a couple of collabs on the [Lit City] EP, all US artists. It might actually be split into two smaller EPs.

You’ve just released the Crying Angels EP, where you re-work a few of your favorite grime tunes. It’s quite a distinctive approach to making cold-sounding grime—whereas a lot of people now seem to be drawing on a slightly cliched “Ice Rink”-style sound.

Yeah, I didn’t do a Wiley tune, did you notice? [laughs] I think it’s because Wiley is at the forefront of grime, so it’s the first grime that people hear, and they go, “Oh, I wanna use that.” They either want to use the “Pulse [X]” bass, or the Wiley drum kit. I did that when I was a kid. But then I’d be like, “Why did I spend all this time trying to find someone else’s sound?”~

Visionist’s Crying Angels EP is out now via Bandcamp. He plays Berlin on Friday, June 14th at Chesters.

Published June 11, 2013. Words by Angus Finlayson.