Afrofuturism Dives Into Brackish Waters With The Book of Drexciya

The graphic novel, released by Tresor, posits elaborate fantasies, but it does so by first confronting the nightmare of Black history and imagining another way forward.

Two stories. The first begins aboard a ship loaded with slaves, bound for the New World. The slavers throw a pregnant African woman into the Atlantic. The final moments of her life are full of pain and fear. But just as she’s about to die, she gives birth. Her baby floats down, away from the surface. Right on cue, a sea sorceress approaches and casts a spell that swaddles the baby in bright green light. The first word of the spell is “Resist!” The second word is “Live!” The baby, and countless others like it, grow into powerful underwater warriors called Wave Jumpers that travel across the ocean, freeing slaves and protecting the downtrodden.

The second story is simpler but somehow harder to follow. America is the greatest country in the world and always has been, except for when a Democrat is in the White House, in which case it’s the worst country in the world. America’s enemies are pathetic and weak and very, very sad, except when they’re all-powerful and rig the system. The American system is perfect. There are just lots and lots of bad apples—a few slave owners here, a few police officers there…

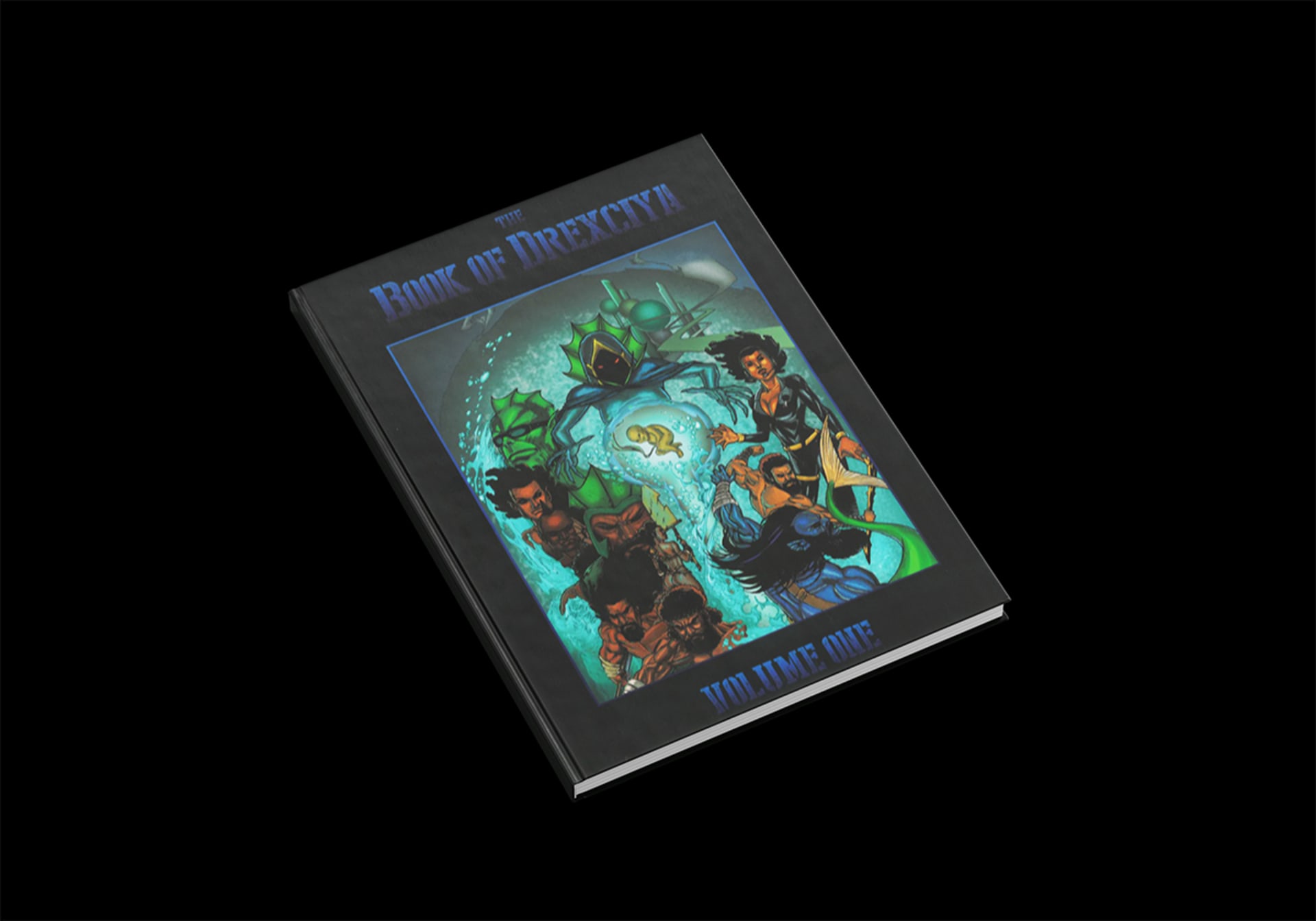

Is the first story any more ridiculous than the second? It features spells and sorceresses, but at least it doesn’t try to sweep the nightmare of American racism under the rug. It treats life as a miracle, not an idle liberty, and suggests that capable people have a duty to help the unfortunate. There is incalculably more truth in the first story than in the second—which is sort of incredible, since the second is the official, state-sanctioned history of the USA, and the first comes from a 71-page Afrofuturist graphic novel, published by Tresor last month, called The Book of Drexciya, Volume One.

If 2018’s Black Panther represents Afrofuturism’s greatest pop culture coup so far, The Book of Drexciya, by Abu Qadim Haqq and Dai Satō’s, is something more modest but equally valuable: a reminder that Afrofuturism was thriving before Marvel Studios embraced it, before This American Life featured it, and, indeed, before the word existed. You can’t really understand the graphic novel without understanding Drexciya, the influential 90s electro duo from Detroit. This seems quite appropriate, since Afrofuturism, contrary to what its name might imply, is almost as concerned with the past as it is with the future. Like all science fiction, it posits elaborate fantasies, but it does so by first confronting the nightmare of Black history and imagining another way forward. At its most inventive (and Haqq and Satō’s work is nothing if not inventive) Afrofuturism remains grounded in hard, painful facts—one crucial reason why its dreams of Black strength and prosperity ring true.

Just as you can’t really understand The Book of Drexciya without understanding Drexciya, you can’t really understand Drexciya without understanding Detroit in the nine years between the fall of the Soviet Union and Y2K. America’s victory in the Cold War should have been a victory for a city that made cars, the quintessential capitalist commodity. Instead, the 90s marked a great emptying-out for Detroit as corporations seized the opportunity to move their facilities to Mexico, leaving the working classes—especially people of color, though whites seemed to grumble most—in a confused rage that has never gone away.

If the official mood of 90s America was triumphalism that hid an ugly truth, Drexciya offered the opposite. Its members, James Stinson and Gerald Donald, rejected the cheesy “bridge to the 21st century” optimism of the Clinton years. In the remarkably fruitful period that began in 1992 with their first EP and ended in 2002 with Stinson’s death, Drexciya developed a rich alternate history for their underwater kingdom, much of it echoed in the pages of this graphic novel. There were benevolent armies and strong female leaders, vast metropolises and all-powerful gadgets—everything the American Dream had promised and then quietly reneged on.

Stinson and Donald make a cameo toward the end of The Book of Drexciya, as “the two best musicians” under the Atlantic: there they are, playing keytars (with webbed hands, no less), dancing through columns of thick blue bubbles. That the two best musicians in this fictional world would use keytars, of all things, is a good inside joke—Stinson and Donald’s real-life weapon of choice was the 808, partly because it was so unpopular in 80s Michigan that anyone could buy it for 100 dollars. In albums like Neptune’s Lair, they used its notoriously inorganic sound to create an elaborate electronic language that—unlike the Space Age Afrofuturism of Sun Ra, an important precursor—evoked water and the organic world.

Water, as you might expect, plays a major role in this graphic novel. As imagined by Abu Qadim Haqq and Leonardo Gondim, water is by turns luminous, brackish, sinister, mysterious, and inviting. Very little happens in the way of plot or characterization, but most of the time I was happy to float along, learning about the Drexciya mythology, drinking it all in. Haqq (a longtime friend of Stinson and Donald and something like the court painter of early Detroit techno) has a sharp eye for bold, foreshortened layouts; sometimes you feel he’s trying to see how many tridents and fins and sea monsters he can pack into one frame. The writing by Dai Satō is—with all due respect to Ghost in the Shell and Cowboy Bebop, the anime classics he co-authored—pretty far from sharp, with a lot of ATTACK!!s and DIE, YOU DREXCIYANS!!s. But even these words have a certain fast and dirty, DIY charm.

That charm, always a crucial part of the Drexciya sound, has been mostly absent from the recent wave of 90s throwbacks. In some sense, The Book of Drexciya is one of these—it’s calculated to charm old fans, just as the duo’s heyday comes around in the nostalgia cycle. But Afrofuturism is interested in repurposing the past, not wallowing in it. If the 90s were in many ways a terrible disappointment, maybe it’s not too late to make them prologue to something better. Resist! Live!

Buy The Book of Drexciya, Volume One now at Tresor.

Jackson Arn contributes regularly to Art in America and has also written for The Nation, Garage and Lapham’s Quarterly. He lives in Brooklyn.

Published June 12, 2020. Words by Jackson Arn.