Dimitri Hegemann Explains The Legacy Of Berlin Atonal Festival

In the early ’80s, venues in West Berlin were getting infected with strange sounds that I’d never heard before. Musicians generated all kinds of noise from scrap yard junk and untuned guitars—a lot of them probably couldn’t have played guitar anyway, at least not in a classical sense. At first these aural experiences shocked me, they broke through my aural comfort zone, but that’s exactly what defined this kind of music. These new forms magically drew me in. Noise had suddenly become music.

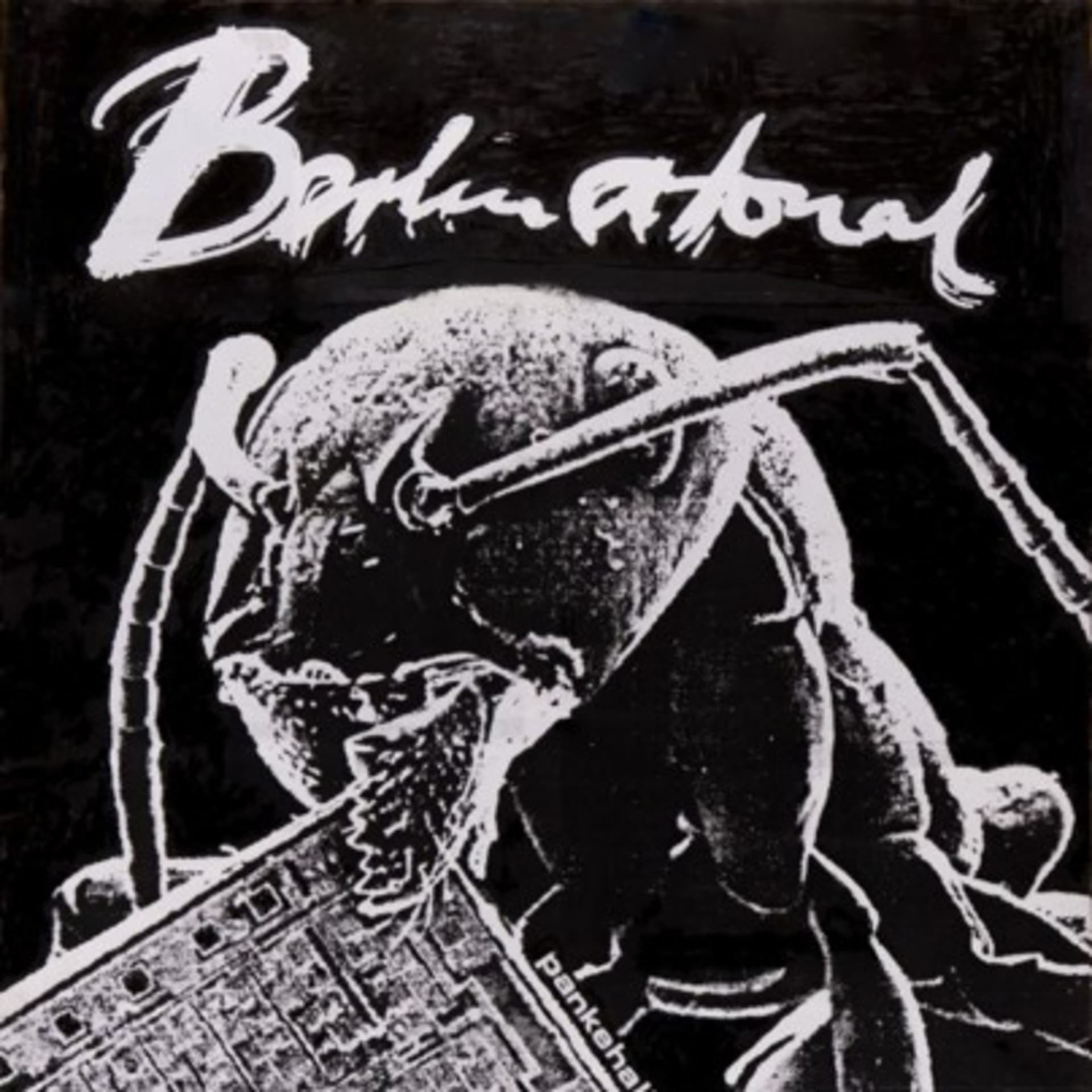

I was rapt by the idea of bringing this new, independent Berlin scene together on stage and in a concentrated form. The “Große Untergangsshow” (“the grand apocalyse show”) in Tempodrom in 1981 labeled these bands as “Geniale Dilletanten” (“ingenious amateurs”) and included such avant-garde artists as Einstürzende Neubauten, Die Haut (“the skin”) Sprung aus den Wolken (“leap from the clouds”), Malaria!, Didaktische Einheit (“didactic unity”), Notorische Reflexe (“notorious reflexes”) and many others. The press described the brutal noise-sounds emitted by these bands as the “Berlin illness” (“Berliner Krankheit”). Despite many a serendipitous experiment, it was actually a pretty grim time. Nobody had any money, nobody felt that the future was bright.

This Berlin illness formed the polar opposite of what was going on in the mainstream at that time, which was stuff like Abba and pop music like Neue Deutsche Welle or New Wave. There was a need to separate from the rock scene and from the sterile artistic endeavors of the academic music scene of Neue Musik. From the spirit of the punk movement grew new scenes like industrial or no wave, which became intensified around places like New York, Sheffield, Hackney and West Berlin.

With financial support from the Berliner Rocksenat we got to produce a program magazine called Die Atonale Inneneinrichtung (“the atonal interior design”), documenting our lives in West Berlin back then, including photos of Einstürzende Neubauten storing their tapes in the fridge, or how Kiddy was living in a tent in some attic. The first Atonal took place at the end of 1982 over a couple of days in the iconic SO36 venue. Groups were working with different elements, media and formats that hadn’t worked their way into music yet: 8mm projections, abstract sounds, field recordings and soundscapes with new instruments. Neubauten worked with sonic objects from the scrap yard, as well as a flex, a hand drill and a jackhammer that accidentally went out of control backstage. Sprung aus den Wolken staged body paintings and daubed a massive screen while they played. There was some pretty precarious work done on ladders, too. It was chaos research. Notorische Reflexe wore white overalls and projected pictures of demonstrations and police violence onto their bodies. It was like a thrilling theatre program, you’d stand in front of the stage and let yourself be fascinated, challenged and unhinged.

The festival didn’t just push mental boundaries, it pushed physical boundaries as well. It ran non-stop from the first day to the last. I didn’t go home, I just stayed for the whole thing and slept there. It was research into how far you could go—your brain would get totally fried.

It was John Peel who was partly responsible for the festival’s success, he talked about Atonal on his radio show for weeks. Yet on the financial side, the festival completely ruined me. I was already broke beforehand and afterwards I had a lot more debts! If you think now about how we ran things back then, everything was hand to mouth. While we didn’t have a clue we did have passion. Over the years, the festival grew way beyond the borders of Berlin. While the first Atonal was focused on homegrown groups, the following events featured more and more important international acts like Psychic TV, Laibach or Test Department and as the audience grew, the venues got bigger. Atonal became a core element in the new movement and grew to become an important factor in the music landscape.

The end of the eighties saw the dawning of a new epoch. I got to know Sheffield group Clock DVA and signed them to my label Interfisch. Not long afterwards I was in Chicago, hanging out with Jim Nash who owned Wax Trax and flipping through demo tapes, when I stumbled across a band called Final Cut. The guys behind this were Tony Srock and a certain Jeff Mills from Detroit. There was a 313 number on the white label, so I called it straight away and said, “I’d really like to put you out in Germany”. I remember how difficult it was to get their record, Deep Into the Cut, into circulation—nobody was interested in it. These industrial beats and heavy-machinery sounds were the beginning of something new and were still a bit rough. At the same time, I had just released Clock DVA’s album Buried Dreams on my label and I still see Final Cut and Clock DVA as being bridges between the old and new scenes. Techno evolved from Deep Into the Cut and Buried Dreams, the logical development into the next chapter.

The fifth Atonal was held in Künstlerhaus Bethanien in March 1990, just after the Wall had come down. It was the beginning of a new scene, shaped by the boundless euphoria and the anarchy of a city on which the authorities had turned their backs for a brief, spectacular period of time. If you see Atonal as being a theatre stage in the eighties, it was the audiences who became the star in the nineties. Suddenly the beat took the foreground, Final Cut with drum machines, Clock DVA with the early Apple 2000. People wanted to dance and in West Berlin nobody danced, after a concert people used to leave the hall. This new way of listening created a new physicality. A new era began with DJ culture and mega parties. The effort and expense of a traditional festival could not compete with the anarchistic and partly illegal activities and locations that offered completely different event and business opportunities: it was a new job to do with completely new challenges. The nineties could begin—and we were well prepared. Atonal, on the other hand, didn’t reflect the times. It was time for a break.

Twenty-five years later, our own success has overhauled us. Techno is played everywhere—from department stores to hairdressers, cafes to clubs—and not just in Berlin. Techno has become pop. This has caused a longing to bring the spirit of the Atonal festival back to life and the need to inject radical experiments back into electronic music. In 2013 we presented over forty artists, including Jon Hassell, Glenn Branca, Moritz von Oswald, Juan Atkins, Murcof and many others. This year we’re happy to present a 4-D sound installation and excellent acts like Ensemble Modern and Cabaret Voltaire and a whole lot of innovative experimental types like Donato Dozzy, Bioshere, Monton, TV Victor or Tim Hecker. ~

Published August 19, 2014. Words by robertdefcon.