An Alternative History of the Fall of the Berlin Wall

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, dropouts, squatters and anarchists made Berlin’s decaying central district of Mitte world famous. Where today young professionals meet for power lunches amidst a constant din of Daft Punk and t-shirt tourists stumble from H&M to Diesel, rubble and smog from the infrastructural ruins of East Germany and the real ruins of the Wall once implied a different future. In the ’90s, a parallel universe with its own music and squatter culture rapidly emerged in Berlin. This is the scene’s surprising oral history, featuring early Einstürzende Neubauten member Gudrun Gut, Atari Teenage Riot frontman and Digital Hardcore Recordings founder Alec Empire, Love Parade co-founder Danielle de Picciotto, Berlin Insane festival founder Steve Morell, Tresor and Berlin Atonal founder Dimitri Hegemann and more.

Alec Empire: Societies can come to an end. With the fall of the Berlin Wall, political circumstances changed radically from one day to another.

Katrin Massmann [former manager of the famous art squat Tacheles and current art designer at Humboldthain club]: The implosion of the GDR had already begun by mid-1989, six months before the Wall came down. The entire structure of the state crumbled in the hands of the apparatus. But no one expected such a spectacular end.

Danielle De Picciotto: Motte [Love Parade co-founder Matthias Roeingh, AKA the DJ Dr. Motte], called me on November 9, weeping: “The Wall is open.” We were all completely beside ourselves.

Gudrun Gut: From one day to the next, Berlin was an uncontrolled city.

Steve Morell: We went out onto the Oranienstraße in Kreuzberg. Nothing was functioning. There were all these cars from the East, massive crowds clogged the streets, and it stayed like that for the next few days. Everyone was getting drunk and going wild. No one knew where it would all lead. After all, there were Russian tanks just outside West Berlin.

Dimitri Hegemann: All the people who sat around quarreling in West Berlin and who had always wanted to do something for the Cultural Revolution now had their chance. The time had come.

Ben De Biel [photographer, former owner of the Maria Club and current press speaker for Berlin’s Pirate Party]: The people from the scene surrounding the Eastern bands Freygang, Die Firma, Ichfunktion and Feeling B acted very deliberately right after the fall of Wall. They knew a building was empty, so they’d take it. The original “cell” was

the Wydoks in the Alte Schönhauser Straße 5, which was occupied in January 1990. Next came the Eimer in the Ronsenthaler Straße 68, a building that was supposed to be demolished and therefore no longer on the property register. So they knew that they would have peace and quiet. And this all happened in Berlin-Mitte, right in the center of the city.

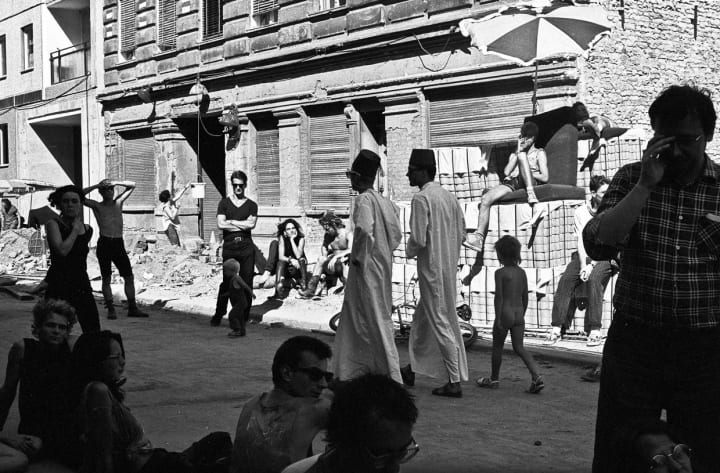

Katrin Massmann: During GDR times, Mitte was not a popular residential area. On the one hand, it was the governmental district. At the same time, parts of Mitte near the Wall were rather shielded. The Oranienburger Straße consisted of ruins, wastelands and decaying buildings, all monochrome, all gray. There was a stationery store, a shop for fruit and vegetables, and a department store—meaning a supermarket and a post office. At the end of the road there was a Christian bookstore and a clock shop.

Ludwig Eben [artist and former bartender at Café Zapata in Tacheles, now runs the Humboldthain club]: The houses were run down, the plaster was crumbling, there were still bullet holes from the Second World War in the facades. The air was thick. Real clouds of fog floated through the streets from the Trabants [East German cars] and from the coal stoves and smokestacks of the decrepit industrial facilities.

Ben De Biel: At night barely every other street light was lit. The city was bathed in dim, orange light. It was dark. Some streets had no lighting at all. There were hardly any cars. In the heart of the city there were hardly any people on the streets at night. It was totally spooky, like in Tarkovsky’s Stalker. Mitte was a dead city.

Ludwig Eben: There were a huge amount of vacancies. But the buildings were also in such a dilapidated condition. There were buildings where you didn’t know if they were going to collapse from one moment to the next.

Jutta Weitz [former constituent of the property management association WBM in the ’90s, which helped support squatters and artists]: Some buildings were supposed to be renovated, others demolished. This fate awaited the historic ruins of the department store on Oranienburger Straße, in which the Tacheles squat settled.

Stefan Schilling [artist and former Tacheles squatter, currently compiling a book about the squat]: When the police didn’t intervene in the squatting of the Eimer, the time was ripe for another building. A date was set: February 13 at 1 p.m. The guys from Freygang had an old fire truck. They drove up to the ruins of this huge department store with the siren sounding and entered the building.

Katrin Massmann: I went there, and there were actually banners hanging on the building, declaring that it had been occupied. Thus the Tacheles was established. The name was apt, as “Tacheles” is originally a Hebrew word meaning “straight talk.”

Ben De Biel: The Tacheles building is an architectural monument, the first steel framed building in Berlin. The building was built with much more steel than was actually needed, because at the time there was still no knowledge of how amazingly strong steel really is. But it was clear to the squatters: although half of the building had already been demolished before it was squatted, it would still last forever.

Stefan Schilling: Some of the squatters had already gained experience in the West Berlin scene. They knew that you have to hold a squatted house; you can’t just go home at night. There were probably two couples who held it for the first week. It was a cold winter, and there was no heating.

Ludwig Eben: I remember we went into a bar. You could go in from the side through the hallway, or climb through the window. There were a few sofas, and you bought your beer through a door that had been transformed into a kind of hatch. There was a big joint being passed around, and we heard about the Tacheles. So we went there. It was March. At the Tacheles, there were just a few people who had formed an association and declared the building occupied. But these few people were nowhere near enough. So we simply joined the group.

Dimitri Hegemann: In West Berlin, the building would have been cleared immediately. But such amateurish actions were possible in the East because the relevant authorities were incapable of acting after the Wall came down.

Ludwig Eben: The Tacheles was meant to be blown up in the near future. During the day, construction workers were busy drilling holes for explosives, bringing in beams and delivering sand so that the house would collapse into itself nicely and symmetrically. Then in the evenings we would continuously destroy what the builders had done during the day. In fact, they only worked for two hours in the morning, then they’d get drunk and go home. Because our different working hours, we almost never met.

Ben De Biel: In the first half of 1990 there were discussions about whether there could be an alternative path for the GDR. There was a spirit of optimism.

Katrin Massmann: Many people were convinced that there must be a middle ground, a point at which the two systems could meet.

Alec Empire: People hoped that the collapse of the regime would not simply result in a takeover by the West. People wanted to create something better, because neither system was perfect.

Jutta Weitz: I can really remember the hopes of that time and the long discussions in the evenings about how to create a better system. But in actuality, the facts were already being decided elsewhere.

Ben De Biel: It tipped quickly when Chancellor Helmut Kohl turned up saying, “come to daddy,” setting the course for a monetary union and reunification. When the first and last ever free elections were held in the GDR in March 1990, where the easter Christian Democratic Union triumphed, there were three months in which the primary discussion was about how to raise as much capital as possible from the 1:1 exchange of 4,000 Ostmarks per person, and for how many family and friends you could quickly open a bank account.

Alec Empire: The East German civil rights activists, which had triggered the events only weeks before, disappeared overnight. Instead, the patriotism of a unified Germany was being proagated through the mass media, with the black, red and gold flag colors flying everywhere. To make matters worse, Germany won the 1990 World Cup in Italy and Franz Beckenbauer proclaimed Germans to be invincible. The right wing attacks ont eh refugee asylums in Hoyerswerda and Rostock-Lichtenhagen in 1992 were directly related to Helmut Kohl’s reunification party.

Ludwig Eben: In May 1990 there was a neo-Nazi attack on the Tacheles. About 120 people attacked the building. One of us, Tombo, had a Molotov cocktail thrown in his face. A mob was at all entrances, ready to kill, just like that. We managed to hold the Tacheles, but Tombo had to spend half a year in the hospital.

Katrin Massmann: The incident led to a wave of sympathy. The blasting operations were temporarily halted and they didn’t continue after it was declared a historical monument.

Ben De Biel: On July 1, 1990, the East German mark was replaced by the West German mark. Half of the East Germans went on vacation and the other half bought a used car. So within two weeks, East Berlin was suddenly full with all these heaps of junk. As soon as they could no longer be driven, the cars were just left to sit there.

Sebastian Drude [Hannover native and linguist who lived in various squatted houses in East Berlin from May 1990]: Around the middle of the year, squatting by Westerners also began increasing. The West Berlin anarchist magazine Interim published weekly lists of vacant buildings.

Gudrun Gut: Young people began pouring in from the West to the eastern part of Berlin. You could try your luck. Anyone could do what they wanted. That was the feeling. Every day something new and improvised was born.

Ben De Biel: At night we sat out on the street in front of certain buildings. If no lights were on in an apartment for three nights in a row, then we’d break in, look around inside, and, depending on how nice it was, we’d install a new lock. In the apartment above what later became the Friseur club we found two working telephones that had access to international numbers. It must have been an office. You could make free calls to America. So we installed a new lock for this apartment and always passed on the key, preferably to Italians, Spaniards or Americans. Anyone who needed to call abroad could go there.

Gregor Marvel [an artist and fashion designer who runs the Friendly Society shop with partner Christian Heinrich]: Until the mid-’90s there were practically no phones in East Berlin. I, like many others, had a notepad with a pen hanging on a string outside the door of my apartment. You’d come home and there’d be a message: “I was here, I’ll try again next week.” And then a week passed. Or you’d just meet at night in the usual places.

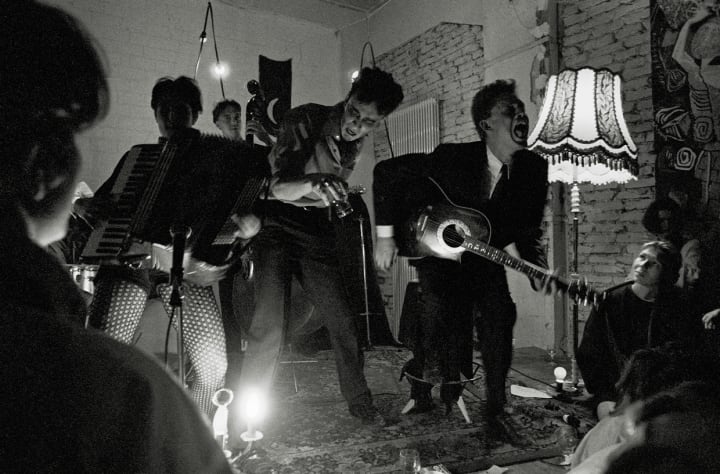

Ben De Biel: Initially, there was only the Tacheles, which is where everyone met if they went out—for drinking and discussing, mind you, not for clubbing!

Katrin Massmann: For people like me, who came from the East, it was amazing that you could suddenly meet in a public space and do something there. The entire area between the Eimer and Tacheles developed rapidly in 1990. There were squatted houses on Linienstraße and on Hackescher Markt. And at the very end of Oranienburger there was another occupied house where the Aktionsgalerie opened.

Jutta Weitz: For a time there were around 30 squatted houses in Mitte. Throughout East Berlin there were over 120. There were also buildings with individual apartments that were squatted. A real microcosm developed.

Ben De Biel: The Ständige Vertretung[“permanent mission”] in the Tacheles was one of the first techno clubs in East Berlin. There was a door to the basement, in which there was only scrap and debris.

Ludwig Eben: Tim Richter and Nick Kapica carried the debris out of that place for weeks and then started a disco, which was very cool. They stole the sign of the Ständige Vertretung, which was the West German embassy in East Berlin. It hung there, well secured behind a bunch of wire, just to make sure that nobody else stole it again. The best DJs in the city were invited to play at the Ständige Vertretung, and suddenly there was a line 60 meters long outside the door.

Stefan Schilling: The Ständige Vertretung was a revelation. You could spend hours dancing with everyone, with or without any reason. There was a kind of non-verbal agreement, and there was this new music, with people like Ed2000 or Dr. Motte. It wasn’t about running a disco for profit, but all about the rush and celebrating every moment.

Gudrun Gut: A huge fire always burned in the middle of the basement. A thin red laser beam cut through the smoke.

Reimund Spitzer [a philosopher who publishes literary texts and runs the Berlin techno club Golden Gate]: There were people who wore gas masks. Some kids brought entire bottles of speed, which they openly consumed on the dance floor. Out of the bottle, onto the hand. Up and away.

Ben De Biel: There were people who were dressed up pretty wild and just walked around. The furrier was closing and had a sale, so everyone was wearing furs. It definitely looked a bit Neanderthal.

Dimitri Hegemann: It was remarkable that young people from East and West Berlin were so quickly able to agree on techno. That was their common thing.

Alec Empire: When we first heard Detroit techno, we knew: this is it. This sound describes exactly how we feel. On that basis, we wanted to find our own language.

Ben De Biel: In Germany there were known DJs such as Clé, Dixon, Tanith, Kid Paul and Dr. Motte. That was techno here in the beginning. The music brought a new vibe. There were the nicer and more open people, and they took the more chilled drugs. Speed and ecstasy didn’t cost much, so both Easterners and Westerners could afford it. On ecstasy no one was ever beaten up. Not even on speed. There was never any stress in the club. Everyone wanted to be a family, to belong together, and to experience something great together.

Danielle De Picciotto: When an entire club full of people is on ecstasy, then the mood, the atmosphere and the behavior changes. There is much less fear of contact. Everyone wanted to cuddle, to sit around together and hug each other. There was a sense of community.

Reimund Spitzer: East Berlin was the hippie dream come true. You occupied a space, put in a sound system and people would turn up. In a little way, they had created the new world, as it should be. Everyone was allowed to be creative in a calm and friendly atmosphere, to have ideas, to dance. In the occupied spaces, only our rules applied: Everyone was equal and everyone deserved respect. We all liked each other because we were all at the same party. This also redefined politics as cooperation rather than conflict.

Dimitri Hegemann: Suddenly it was back, the hippie movement. At least, that was how I had always imagined it. People embraced in the morning; you said goodbye differently.

Reimund Spitzer: That was the end of punk negativity. Anyone could come, no matter how they looked, could belong, and was greeted with a smile.

Alec Empire: That attitude stems from the earliest days of techno. It was before the Wall came down, when a few dozen West Berliners met in the UFO or in the Turbine and became convinced that this music was the future. It was no longer based on what we knew from the 20th century. It resisted all categorization.

Gudrun Gut: The idea that there is no longer a star who stands on the stage celebrates his or herself was an idea from the ’90s. Instead, everything blended—DJ, audience and music. Everything was equal. The moment is what mattered.

Alec Empire: Soon after the Wall came down the first raves started, such as Technozoid or Elektrokohle Lichtenberg in East Berlin. There were countless locations, so people just did stuff everywhere. Those kinds of parties were common. They weren’t clubs, just improvised, like, “That place is empty—let’s bring in a PA!”

Gregor Marvel: You needed an electrical outlet, a fold-out table, two cases of beer, a bottle of vodka, some paper cups and maybe some bitter lemon. Then a mixer, two turntables, speakers and strobe light. And a fog machine, of course. There wasn’t anything else. Anywhere you saw a red lightbulb shining or there were some candles set yup, then you knew: that’s a bar. Rows of apartments were seized for temporary bars.

Ben De Biel: The furnishings could be found on the street. People simply put everything that reminded them of the GDR outside the door as bulk waste. Some of it was really cool stuff. You could just take it away. Of course, that was a boon for every club.

Danielle De Picciotto: I remember a party on top of a roof where everybody was supposed to bring a rose. The whole floor was covered with roses at the end. Then we held a party in a basement, with the motto “black and white.” So everybody came in black and white. Everything happened via word of mouth.

Gudrun Gut: You’d get a secret invitation from someone, and because it was in the East, you’d go.

Reimund Spitzer: The authorities didn’t prevent it, but only because they didn’t even notice for a while. It isn’t the decision-makers, politicians and officials that made Mitte and ultimately all of Berlin into a big deal, but a bunch of freaks, dropouts, anarchists and squatters. It was the Anti-Berliners, as they were called by the politicians.

Ben De Biel: On July 24, 1990, shortly after the introduction of the Deutschmark in what was still the GDR, the East Berlin courts imposed the so-called “Berliner Line” from West Berlin in the eastern part of the city. This meant that from the time on, no new squats were tolerated in the East and had to be cleared within 24 hours. However, the buildings that had already been occupied were allowed to negotiate contracts.

Ludwig Eben: At the same time the work of the “Treuhand” trust began, which was in charge of selling off the state-owned assets of the GDR, often to dodgy businessmen from the West. Nothing remained of the original thrust of the civil rights campaign to distribute the national wealth to the citizens. Within just five years, 85 percent of East German assets fell into West German hands. Another 10 percent went to international investors. The Tacheles was merely one of many pieces in this large-scale redistribution process.

Jutta Weitz: It became a true race against time. The principle of “restitution before compensation” had been set in in the reunification treaty. This meant that property had to returned to former owners after the unification. Had the owners instead been compensated, there would have been a lot more time to develop things calmly.

Sebastian Drude: On the night of October 2, 1990, some of us went through the district with spray cans and painted over the street names with black paint. It was because we feared that with the unification of the two German states on October 3, the western police would come and start evicting. That was meant to confuse them.

Ben De Biel: On November 12, recent occupations in the Pfarrstraße in Cotheniusstraße in the neighboring district of Friedrichshain were cleared within a few hours by hundreds of police. Squatters in the nearby Mainzer Straße expressed solidarity and demonstrated. Although the Mainzer Straße had largely been occupied in April before the Berliner Line came into effect, the squatters came to the conclusion that Mainzer Straße would soon be under threat, so they prepared themselves. The first Molotov cocktails were thrown during a solidarity demonstration, and a barricade was built at Frankfurter Allee. Someone actually stole an excavator and dug trenches.

Steve Morell: Many people from West Berlin and West Germany lived in Mainzer Straße, but also East Germans, Spaniards, French, English. It was a lively mixture.

Ben De Biel: Half the street was occupied, 13 houses all together. There was a women’s and lesbian’s house and a queer house that was occupied only by gays. Most squatters came from the Kreuzberg political scene. This meant that the militant political attitudes from the West had come to the East. In the Mainzer Straße it was common knowledge: The police are the enemy. So they armed themselves heavily.

Steve Morell: The new forms of collective coexistence that had only recently emerged suddenly found themselves threatened. On top of that, property owners turned up that could not be argued with. That fueled aggression in the scene, and it became radicalized.

Sebastian Drude: It became increasingly clear to the squatters in the Mainzer Straße that an eviction was imminent. These occupations were a thorn in the side of the city. They wanted to decapitate the East Berlin squatter movement. Two or three days before the eviction, the first convoys came down the highways with police from Hamburg, Hannover and Munich. It was provoked two days earlier, when the police smashed the squat’s windows with water cannons. The squatters threw stones.

Ben De Biel: In advance of the police’s arrival, people were hopping around on one of the roofs in the Mainzer Straße. They tore down the facade cladding and threw the stone slabs on the road.

Steve Morell: Razor wire was mounted on the roofs. Back then you could get it for free. You just had to go out to the old East barracks, and it was lying all around. In one of the abandoned military barracks, even tar machines and spark generators were found and taken. The police at the eviction on November 14 had to hold metal plates over their heads, because the squatters were pouring hot tar down from the roof. The infamous electrical traps were built from the spark generators. Of course, they provided signs that read “380 Volts.”

Ben De Biel: It was the most massive use of police force in Berlin in post-war history: 3,000 policemen against 500 squatters.

Steve Morell: I watched it from the outside. There were helicopters, from which the police roped down onto the houses. When the police got into apartments, they made short work of it and threw everything out the windows. The police were extremely violent in these operations. They’d just smash a baton in your face or over your head—they didn’t care. To the police, the squatters were scum. The scenes were reminiscent of a civil war.

Ben De Biel: In Mitte, there was a different mood. In summer we snuck into the Monbijou children’s pool at night, floated candles and splashed around a bit. Then a policeman came and said, “What are you doing there?” “Well, we’re swimming.” “That’s not allowed!” In the end he allowed us to stay, as long as we took away our trash. Political radicals would have turned a situation like that into an opportunity to insult the police. Of course, the situation would have escalated.

Reimund Spitzer: Scenes like that only turned out so well because the authorities were overwhelmed and had to overlook many things if they weren’t really serious protests.

Jutta Weitz: Since the return of buildings to former owners didn’t happen very quickly, unexpected room to maneuver arose for WBM [public residential apartment management services], who still managed a majority of the properties in Mitte from the GDR days. First every single case had to be examined by the newly created Office of Unresolved Property Issues. There were houses with ten different applicants, all claiming that it was theirs. They had to go house by house and review the registries and inheritance records. So I went to all the occupied houses one by one to introduce myself as an employee of the WBM. On the other hand, I spoke with the former owners. I didn’t want to wait until a situation arose that would have led to an eviction. In all the houses where there was any legal possibility, we entered established rental contracts. If there were vacant WBM buildings with commercial spaces, then I searched for groups for them and systematically spread the word that a place was available for the price of heat and electricity or very low rent.

Dimitri Hegemann: The establishment of the “temporary use” and the resulting temporary use agreements were very important for the development of Berlin. This created the possibility of legally using places to try out ideas, at least for a certain time, until they later fell back into the owners’ hands.

Alec Empire: Whether legal or illegal, new locations were continually created beneath the city. Berlin has a very specific kind of damp, musty cellar with rusted pipes and dilapidated electrical wiring. The lighting was improvised. You’d hang a construction lamp so you wouldn’t fall down the stairs. It was March 1991, the Tresor opened a very typical club for that time, except as a former vault of the Wertheim department store in Leipziger Straße, it additionally had these old safe deposit boxes and heavy steel mesh doors as a bonus.

Dimitri Hegemann: The Berliner Tagesspiegel newspaper once described the vault as a perfect shelter from a Feng Shui point of view.

Gudrun Gut: It was dark and damp, it smelled like a cellar, but with hardly any light and brutal sound, and very minimal music. It wasn’t funny at all. Jeff Mills was also not a fun event. It was really hardcore.

Steve Morell: I don’t know how many liters of liquid for the fog machine were used per night in that vault. Sometimes you couldn’t even see your hand in front of your eyes.

Dimitri Hegemann: I can remember one morning in the garden of the Tresor, which was a place of total calm right in the center of the city. We were the first to settle there. Then the Ministry of Finance set up across the road. Some of the employees who came to work early even danced with us shortly before starting work. Somehow in the morning we always had the feeling of having done something during the night. I hadn’t danced or taken any drugs, but I must have done something in those 10 or 12 hours because I always had new insights from the conversations. Sure, 50 percent was silly chatter, but the other 50 percent were substantive approaches that were actually pursued. You also met colleagues from similar establishments. Things were discussed that would change Berlin a lot in the following years. For the first time there was a space not just to think about something different, but to let it take shape. We were brash enough and didn’t spend long questioning, but quickly established facts: the clubs and art venues, musical developments, the Love Parade.

Danielle De Picciotto: We wanted to take what we were having fun with and what we believed in out into the open and not always party in these basements. That was the original idea behind the Love Parade. It was also a movement away from the existentialist, heroin-heavy melancholy that was so typical of West Berlin in the ’80s. It was about a kind of joie de vivre.

Dimitri Hegemann: When house and techno arrived, a community emerged really, really quickly. Certainly the euphoria surrounding the fall of the Wall helped, but it was especially about the new music. It was fresh. “X-101”, our first 12-inch on Tresor Records, appeared in the summer of 1991. “Klang Der Familie” by 3phase with Dr. Motte came out in 1992. The title describes the spirit of the times: “The Sound of the Family.” We somehow all liked each other. We got along. The atmosphere was really good.

Ben De Biel: Soon property started getting returned to its former owners. At a certain point it became clear who owend the property, and then it was often directly sold or put on the market immediately. That attracted investors who shopped for cheap real estate and bought it for peanuts. Entire streets.

Jutta Weitz: At some point it just became: buy low, renovate and resell immediately. That led to a very different kind of commercialization. You could write off the purchases and renovations for tax purposes for up to 100 percent over ten years. That was a special rule. That paved the way for entirely new economic models.

Ben De Biel: Strange things began to happen in Mitte. Whenever Dorothee Dubrau, the District Councilor for Construction, would accidentally crash into a house. Then the house would have to be demolished. For example, that’s how the Elektro squat was torn down even though it wasn’t supposed to be.

Jutta Weitz: An excavator “accidentally” crashed into a side wing of Neue Schönhauser 10. It was vacant, sure, but there was no demolition permit. Then suddenly there was one.

Ben De Biel: In 1992 there was a fire in the attic of the apartment buildings next to the Tacheles. 40 or 50 people lost their homes.

Ludwig Eben: The fire department let both houses burn down. We became extremely agitated, so the firefighters called the police. The police actually got out of the car wearing Nazi helmets. A good shock, that was. They were just waiting for us to start a fight so that they could haul away the whole Tacheles crew. They saw squatters as enemies of the state. When the fire was out, the order came: “Water on!” The houses were then drenched. That way the fabric of the building was guaranteed to be ruined, and the oldest buildings in the Oranienburger Straße were taken from us. Eventually, they put a cardboard roof over it, which could hardly withstand the rain. In the end, everything was so destroyed that you could drill a hole into the wall with your finger. Then it had to be torn down—just so someone could put a hotel there.

Ben De Biel: Meanwhile, after the peoples’ first spending spree, the lights really went out in the East. Just as the people left their old GDR junk out on the street, the East German economy was abandoned. Soon, every other person was unemployed and broke.

Ludwig Eben: A typical scene: I’m in a small supermarket, and in front of me is a guy with a bottle of schnapps and two cans of dog food. He doesn’t have enough money, so he gives back the dog food. There were so many total alcoholics, utterly wasted, with bodies that were already completely trashed. They were the first people to disappear from Mitte.

Ben De Biel: There were countless state-sponsored work creation schemes. Tons of money was pumped into the social system.

Ludwig Eben: These were measures to tranquilize the population of the former East. People in yellow suits tore down the same factories where they used to work, and this was a job creation scheme! At the time, practically everyone at the Tacheles who could raise an arm got a state job repairing and rebuilding the Tacheles. They received between 1,300 and 2,000 Deutschmarks per month. However, most of the recipients were never there or were doing something else, so you couldn’t plan on them actually working. Only a third really tried to help establish an infrastructure in Tacheles. But we succeeded. By 1992 the place was firing on all cylinders: There was the Zapata, the Ständige Vertretung, theater productions, concerts and workshops open on both floors. They were used by artists who worked there. The building attracted hundreds of people daily. Suddenly everything started working! That was even more valuable for us than oil or diamonds.

Reimund Spitzer: You could walk forever through Tacheles. It was like a trip.

Stefan Schilling: There was someone there with a big drum that shot out smoke with every hit. He’d take aim with a preference for people who didn’t yet know the effect. Or you’d walk into a room and hear all this loud laughter next door: People were filmed and the images were distorted into bizarre grimaces with a magnet on a TV screen in the next room. It was a way of laughing people’s egos down to size a bit. Joseph Beuys’ extended definition of art and social sculpture became the agenda of a whole generation, not only for artists that recognized explicit references. Suddenly, everyone was an artist and were focused on the creation of new social relationships.

Reimund Speitzer: The German Chainsaw Massacre by Christoph Schlingensief was showing at the cinema on the third floor, called Kino Angenehm (“Pleasant Cinema”). In the film, the fall of the Wall sets a West German butcher family into a murderous frenzy. They kill visiting GDR citizens in a seedy hotel kitchen. The sound system was insanely loud. There was a lot of yelling. They were yelling the whole time, actually.

Katrin Massmann: In a circus arena in the auditorium of the Tacheles, people wearing shiny bondage costumes were led around in chains. It was Bestia Pigra by the R.A.M.M. theater group. A woman with huge breasts was lowered down from above on a rope, accompanied by electronic sounds and aggressive texts.

Stefan Schilling: Suddenly a huge door opened, and in the room behind it a band was playing. Upside down. They were the Elektronauten, with Ben De Biel. It was like they were standing on the ceiling.

Alec Empire: For those who wanted to restore order, it was already a state of emergency. For us, it was zero gravity.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2014 issue of Electronic Beats Magazine. Click here to read more from the magazine.

Published September 22, 2015. Words by Robert Defcon, photos by Ben de Biel.