At the Lucky Cloud Loft Party, Records Are Selected to Match the Arc of An Acid Trip

Photos by Matt Cheetham.

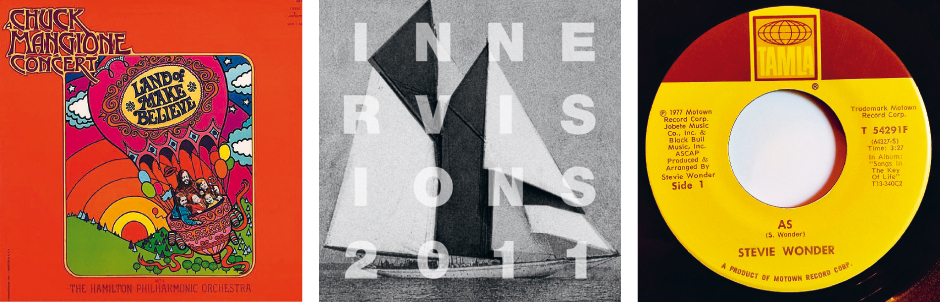

Three records selected by Tim Lawrence that reflect the phases in an LSD experience invoked at a Lucky Cloud Sound System party, top to bottom:

Chuck Mangione with the Hamilton Philharmonic Orchestra, “The Land of Make Believe” [Entry]

Osunlade, “Envision (Âme remix)” [Circus]

Stevie Wonder “As”: Re-entry

The Lucky Cloud Loft Party began with David Mancuso, who has been running private parties in downtown New York since 1970. I met David while I was researching my book on the rise of the city’s DJ culture. Since June 2003, Colleen Murphy, Jeremy Gilbert and I have been running the party according to the principles of David’s New York parties. For the first 11 years, we held the party in a converted power station with springy wooden floors. We decorated the room with hundreds of balloons, just like we were putting on a kid’s birthday party, to evoke a time of joy and freedom. We put out a spread of food to give guests energy for the marathon dance. And we set up the room so that the first thing a dancer would see would be the party room and not the booth, because the dance floor is the focus of the party, not the person selecting records.

David has never called himself a DJ. Instead, he prefers to call himself a “musical host,” because he is a party host who also happens to select music that he thinks his friends will enjoy. The sound system is almost entirely analogue and is made up of high-end stereo equipment that is highly efficient and sensitive, including Klipschorn speakers and Koetsu cartridges. It only supports vinyl playback because vinyl is the warmest and most detailed medium. The overall aim is for the system to reproduce the original recording as accurately as possible because the energy of the party will rise in correlation to the musicality of the experience.

Whether the role is taken up by David or by someone else, the musical host will play the entire party, from 5 p.m. to midnight, drawing on a wide range of sources that stretch from acid rock to disco to house to minimal techno—because the world is diverse and magical, so why restrict the music to a single genre? Records are also selected to match the arc of an acid trip, because LSD was the drug of choice when David held his first dance party on Valentine’s Day 1970. He wrote the words “Love Saves the Day” on his party invites for a reason.

David learned from Timothy Leary that the acid trip is comprised of three stages, or three “bardos,” and he selected his records so they would match the intensity of these phases: the gentle, playful beginning or “entry;” the deeper, more introverted transcendental “circus” that follows; and the more open, more social, more uplifting experience of the “re-entry.” David was the very first person on the downtown party scene to take dancers on a kind of musical journey, and although that’s become something of a lost art in contemporary club culture, it remains important to us, whether we choose today to take LSD or not.

Whatever the stage of the party, the musical host won’t take the sound system above 100dB because anything above that can start to tire or even damage the ear. Early on we found that quite a few people would come up to us and ask if we could encourage David to play the music louder—because we’d all become used to hearing loud bass music played at 120dB and above. What’s interesting is that we no longer get anyone asking us these questions. Our ears have adjusted to a new way of listening.

Another distinguishing feature of the parties is the absence of a mixer in the sound system. David decided to get rid of this piece of equipment after he concluded in the early eighties that a musical signal becomes more powerful if it passes through the least number of electronic stages possible from the vinyl to the ear. He decided that the musicality of the experience was more important than his ability to mix records; or, as he put it, interfere with the intentions of the recording artist. Getting rid of the mixer also enabled David to properly shift the attention of the party from the booth to the dancefloor. Of course, by now it’s become mandatory to have non-stop mixing in contemporary party culture and people assume that any gap between records would lead to a decrease in the energy of the party. But what we’ve found in London is that the pause has become a moment of heightened intensity, when people can clap, scream and whistle, showing their appreciation of the music. And that to us is really quite thrilling.

This article was originally printed in the Fall 2014 issue of Electronic Beats Magazine.

Published November 05, 2014. Words by EB Team.