Disco Professor Daniel Wang Digs Into The “Infinite Past” To Inform The Present Of DJ Culture

“If you're just mixing tracks mindlessly, you might as well be just a Spotify playlist.”

There may be several reasons why Daniel Wang has been labelled the ‘Disco Professor’ over the course of his career. His academic education being one of them, his treasure of knowledge when it comes to music history and theory being another. The critical thoughts he added as liner notes to some of his releases and the unfolding impression of him as disco’s elder statesman at the age of 50 might play their fair share in it, too.

The California by way of Taiwan native spent his student years in Chicago and New York, delving into its vibrant Afro-American club scene outside of the lecture hall. Since 2003, he’s lived in Berlin as a critical observer of and contributor to the city’s club scene, all the while maintaining his international reputation as one of the most educated and flamboyant figures of the game.

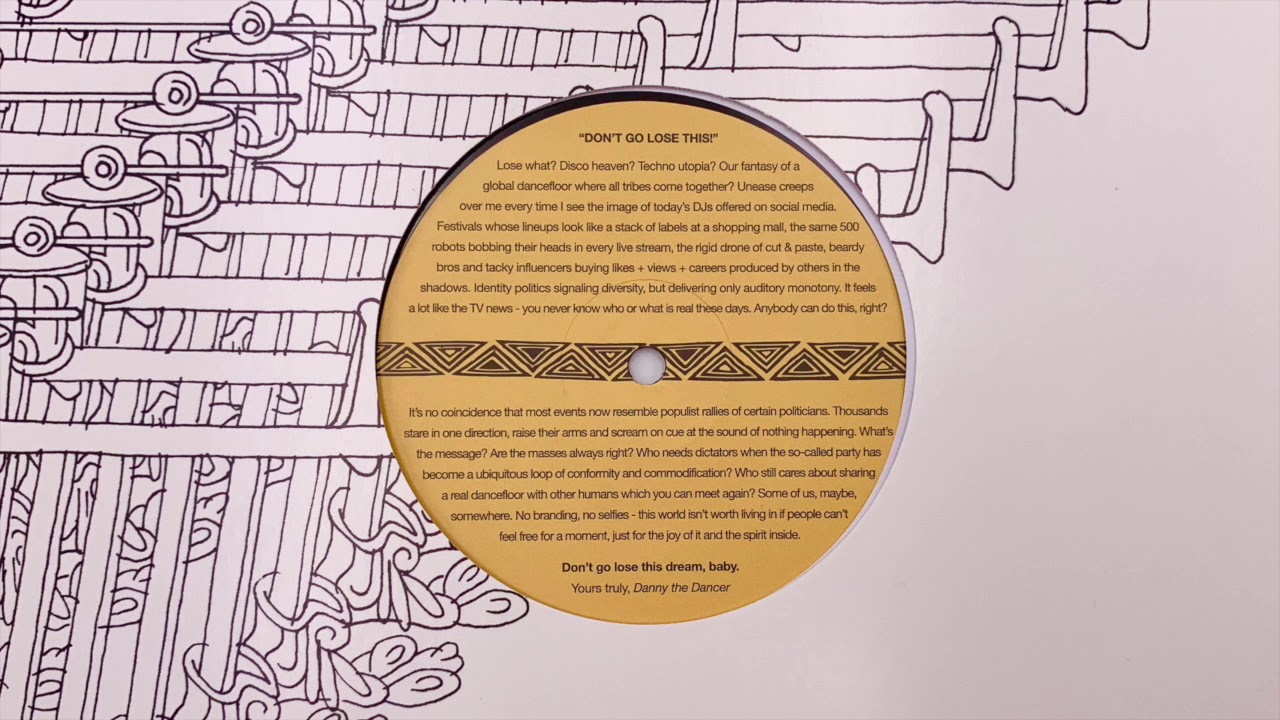

For 25-plus years now, he stands as one of the pioneers of the genre known to dancers these days as ‘Nu Disco’. The term that falls short, though, taking into account Wang’s constant revision and refinement of disco music and the exhaustive research of its roots and history. Along the way, the de facto Berliner established his renowned label Balihu Records; Rush Hour compiled its essential material as a retrospective in 2009. He’s released on Morgan Geist’s Environ, as well as on imprints like Playhouse, Ghostly, and Eskimo Recordings. Just recently, after a longer release hiatus, he put out a new Disco Edit 12″, sampling Hugh Masekela’s 1984 classic “Don’t Go Lose It Baby.”

Daniel Wang demonstrated his expertise for record digging through our “5 Favourite B-sides” series, and you’ll hear and see more of the Professor soon on Electronic Beats TV. To get more into detail with his multi-faceted past and also his elaborate attitude when it comes to the current state of club culture, we sat down with him and kicked off a conversation.

As someone who has had such a long career in music, how do you recreate the sense of naivety you had at the beginning?

It’s hard to recreate that naivety, but I think at a certain point in your career, it is actually possible, because you’re back at that spot where you started. And that’s how I feel now. I know now what I want to say and I’m able to say it–thanks to all the gadgets and friends who taught me. So even if you might not be able to recover naivety, you can go back to that place of sincerity.

How important is it for a DJ to know the history of music?

Some people tend to get stuck in the things they learned as a teenager. In Berlin, you have all these 80’s and Depeche Mode parties, and I guess you can say people going there are really stuck. In the mid-90’s I stopped absorbing new dance music, because everything sounded the same. But I didn’t stop absorbing music in general. I listened to more classical music, more bossa, and a lot more jazz. Today, more than ever, I consider myself as non-traditional and non-conservative, but maybe I would call myself a preservationist. Everybody knows it, but many people wouldn’t admit it, that DJ careers today are built on downloading new tracks and selling new stuff that no one needs. It’s a lot like clothes.

Do you see significant historic reasons for that matter?

A changing point was when MIDI came along in 1986. Before that, you would only go into a recording studio if you were a really good live musician with training and understanding of classical, jazz, etc. You would do several takes and then you had the best engineers to fix and arrange it afterwards. So there was a lot of knowledge and expertise needed up until 1986–especially in that golden era between the mid 70’s and mid 80’s. Without that knowledge, I think people are not qualified to call themselves DJs, because they don’t understand what happened in that period. If you don’t understand what happened culturally, technologically, musically, black people, white people, all the mixing of cultures, you can’t call yourself a DJ. I’m sorry. People who stick electronic music, just to this 4/4 formula and the 303 or the mindless minimal techno stuff, you can call yourself a DJ the same way McDonald’s can call itself a restaurant. You serve music as they serve food: it’s not good food, it’s not interesting, it has no content, and it’s bad for the people who consume it.

What do you think about sound nostalgia and people trying to reproduce certain sound aesthetics? Wouldn’t it be nice to make a cut and completely start from scratch with music?

Interesting thought, but nobody really starts from zero. Everyone has a library in their head. And some people have a more interesting library than others. The present is just a tiny moment, but there is always an infinite future and infinite past.

But it’s true, sometimes it’s good not to know too much. Like the jazz musicians in the 1930’s. Some of those people were really destitute African-Americans or Irish, Jewish immigrants in the US. All they had was their natural sense of rhythm and harmony. When people today try to formalize these things, they are formalizing things that happened naively, because they had to find colours and textures that hadn’t been there previously. Same thing with Jimi Hendrix. Millions of people are trying to play like him, but Hendrix was just being himself when playing a solo.

How do you think about what happened in the 80’s here in Germany or in the UK?

I love that stuff. Also, I don’t want to over-valorize so-called “American black music” or all the music that has an African influence. This music is very varied. All these players had different intentions, different levels of musicality. And I also think that black music can be horrible, too–not just current music, but also in the past.

By loading the content from Soundcloud, you agree to Soundcloud’s privacy policy.

Learn more

There is this theory you can only be a good DJ, if you’re a good dancer…

I thought about this a lot. I know many exceptionally good dancers with horrible taste in music that are also horrible DJs because they reduced dance-moving to a technical aspect. They have a metronome running in their head, and they can do the same movement on any music. That’s boring. It turns dancing into a purely physical, mechanical exercise and takes out the aspect of human expression. The best dancers let their bodies react to the music.

I’m a pretty good dancer, but not the best. And I think I’m a good DJ, because I have a sense of what feels right and I do believe you should be interested in dancing to be a good DJ, but it also depends on the audience you’re appealing to. Especially nowadays. This is again quite critically, when you’re at big festivals, they don’t even offer a dance floor, it’s a big stadium where everyone is facing the same direction. And there are also people who are less interested in dancing than in the pure essence of music, the physical excitement of hearing frequencies and bass, so it’s almost a purer form of listening. But this is wrong, because the whole purpose of dance music is to introduce a physical, interpersonal participation, which was absent in traditional, formal concert halls. To turn the dancefloor into a concert arena is gutting dance music of its original meaning and replacing that with only commerce.

How about the library aspect when it comes to certain tracks and how they can fit together in a DJ set? Where is that knowledge coming from?

I often go to other people’s gigs and realize they have bigger collections of stuff. They have titles I don’t know of, and I wish I knew them all. But I think I have a brain that is good at classifying and picking out the interesting details. A good composer or arranger picks up on the melodic contours and when I DJ, my brain tries to make these connections.

Recently, I mixed “Fascinated” by Company B, which is in F minor and 120 BPM, and thus the same as my remix of the Hugh Masekela track. At that point I didn’t know that, but I started mixing them together in a club, and I realized they mix together perfectly. If you’re just mixing tracks mindlessly, you might as well be just a Spotify playlist. But if you want to make music interesting to people as a DJ, you’re showing connections, you’re showing how things are related to each other.

It’s like human beings. We all are different, but we all have something in common. The books we write and read and the music we compose, they are also connected to each other, because they are the expressions of how we feel inside. And when you’re showing how these things are connected to each other, hopefully you’ll make people feel connected to each other, too.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. Daniel Wang will be back soon on EB.TV in his own series “Talking Dance Music”, analyzing significant tracks of the past, their historical impact, and providing his musical theory knowledge.

Published January 15, 2020. Words by Andreas Richter.