Before Hot Mass: The Man Behind Gay Pittsburgh’s Nightlife

The unlikely American city of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania recently entered the international clubbing consciousness thanks to a gay bathhouse-turned-techno club called Hot Mass. While those parties have dominated popular knowledge of contemporary midwestern techno, the city actually has a rich history of queer social spaces that laid the groundwork for the now-popular nightlife destination. And it’s mostly thanks to the efforts of one man, Robert “Lucky” Johns, that the once-elusive scene exists and has since transformed into a robust niche worthy of global attention.

This illicit party culture was shaped by fundamental changes that occurred in the region during post-war industrialization; culturally, Pittsburgh was—and to a certain extent, continues to be—informed by blue-collar working class identities dependent on hard labor and deeply ingrained heterosexual ideologies of masculinity. Outwardly homosexual behavior was severely condemned and even illegal until the Commonwealth v. Bonadio court case in 1980, and serving queer people in bars and restaurants was considered illegal until the early ‘80s.

Unlike bigger and more cosmopolitan cities like San Francisco and New York, which cultivated gay bastions concentrated in specific neighborhoods, queer-friendly spaces in Pittsburgh were dispersed throughout the city, likely due to an intense scrutiny that threatened them in more commercial districts. In the mid-20th century, anti-gay sentiments manifested in direct repression from the government, including a campaign investigating allegedly subversive homosexual activity. According to the catalog that accompanied an exhibition on queer history by Pittsburgh historian Harrison Apple, over a dozen policemen formed this so-called “morals squad” to witch-hunt local homosexual “degenerates.” Though the members were eventually convicted of embezzlement, fraud and collusion, they represented a larger conservative social ideology that permeated the American midwest and provided a catalyst for Pittsburgh’s gay community to organize discreet, underground spaces that would permit and revitalize LGBTQ identities.

Although those living in western Pennsylvania had a more difficult time forging a strong community than their counterparts living on the coasts, queer social spaces did begin to appear in the ‘70s and ‘80s. “A shared patois of drag names, passwords and codes began to evolve and unite a formerly fractured queer community,” notes Pittsburgh Queer History Project Co-Director Dr. Tim Haggerty in the online archive. Much of this nascent gay nightlife scene, he goes on, was made possible by Robert “Lucky” Johns, a proprietor and political pioneer who was ordained “the Pope of gay Pittsburgh.” Johns created exclusive social spaces for the development of gay, lesbian and trans communities: The Transportation Club in 1967; The House of Tilden in 1970; The Travelers Social Club in 1980. His first club initially had 200 members and was officially registered as a traditional fraternal organization with a charter, a purpose, a membership and a “clubhouse.” But behind closed doors, it became a space for queer identities to come together.

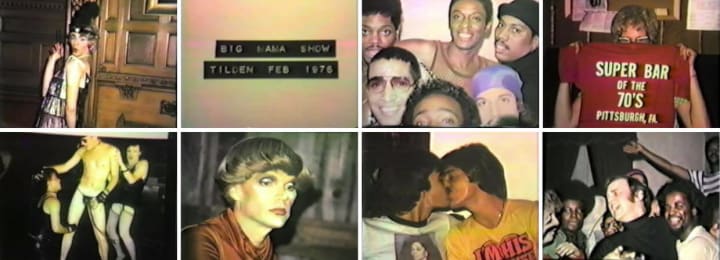

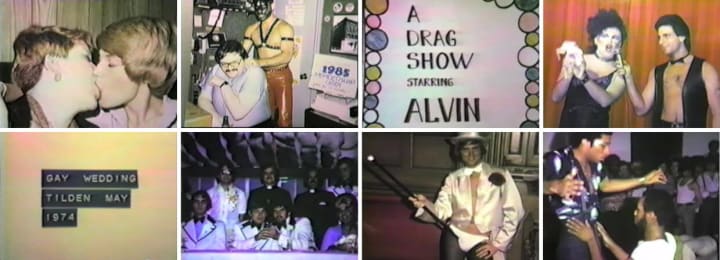

The first 200 members were exhilarated by this shift in the social landscape, and by 1970, the list of Transportation Club affiliates included over 1,000 people. Its successor, House of Tilden, was even more popular, boasting a list with nearly 3,000 people on it. According to a local newspaper, Johns’ clubs collectively may have hosted up to 30,000 members total. Enrollment in one of Lucky’s clubs translated to a kinship that extended protection to a covert homosexual social world. Special entrance cards granted to members allowed access to a likeminded community, and many people found work as bouncers, bar-backs and waiters—which was denied to them in Pittsburgh’s mainstream heterosexual society. It also paved the way for many local musicians and DJs, as the House of Tilden also operated as a disco that frequently hosted balls.

Guests, employees and performers took pictures that Johns displayed on the walls of his successive clubs. Apple, who helped to archive Johns’ photo collection in the Pittsburgh Queer History Project, says the images are like a family album or a visual diary. “Sifting through the images, you can see people grow older, transition, meet lovers and disappear,” they note on the Lucky After Dark exhibition’s catalog. Johns’ clubs rose and declined in popularity throughout the years as many in the gay community moved to larger cities like New York during this period, but Apple notes a distinct downward trend starting around 1980. After that, the social emphasis on bars and clubs in Pittsburgh began to shift towards activism and self-care in the face of the AIDS crisis.

Those years were fraught with apprehension, fear and solidarity as communities came together to support friends afflicted with HIV/AIDS. Clubs like House of Tilden and Travelers Club hosted AIDS benefits to raise money for sick community members, and more informal events like picnics and rallies took place during the light of day. Events like these were especially important as many of the city’s health officials had difficulty providing formal channels to help the clandestine queer world because of its staunch secrecy. Anthony Silvestre, a University of Pittsburgh professor and director of its program in LGBTQ Health, said that “It was clear that we had to overcome some serious obstacles. There was a sodomy law on the books until 1980. There were still police raids in gay bars, and gay people could be subject to violence and job discrimination.”

In addition to being held under attack by Pittsburgh’s conservative public, the LGBTQ community now had to face an extraordinary medical disaster. Ads in gay media outlets like OUT Magazine offered help and attempted to destigmatize the conversation surrounding AIDS in the larger Pittsburgh community. Despite these efforts, however, The House of Tilden was forced to close its doors in the late ‘80s after its membership suffered severe blows from the disease’s spread and crackdowns from law enforcement. Documentation of LGBTQ nightlife throughout this period is oblique, and the gay archival absences that exist throughout the ‘80s are conspicuous—not coincidental. Gay and lesbian nightlife stagnated and eventually lay dormant for almost three decades following the epidemic.

And then, in 2012, Hot Mass breathed new life into Pittsburgh’s queer social spaces. As we reported in a feature written last year, the after-hours hotspot has been one of the first Pittsburgh spaces to adopt the legal status of a private club since the AIDS crisis. Unlike its predecessors, however, it hasn’t faced raids and crackdowns. This seems a result of the city’s recent efforts to adopt progressive policies aimed at bolstering the post-industrial economy and supporting the city’s creative scene.

Like Transportation Club or House of Tilden, Hot Mass is a gay, members-only club, though it does have an audience that extends beyond the LGBTQ community. While its predecessors may have been more explicitly gay than Hot Mass, their exciting atmospheres drew some straight attendees throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s that later formed the foundation of Pittsburgh’s contemporary club scene. Hot Mass has also perpetuated the tradition of epic all-night parties, which happen every Saturday thanks to a rotating roster of promoter groups that have recently popularized house and darker shades of techno in the city’s music scene. To many, the club embodies various forms of freedom: the dance floor is a space that allows for musical experimentation, but it also enables queer identities to exist in a still-conservative midwestern city. Spaces such as these are not cordoned off, but are the product of decades of work performed by an expansive and liberal community.

Johns’ Pittsburgh narrates the evolution of special places like Hot Mass. It also sheds light on a tight-knit group of people that was not shaped by the tabula rasa construction of gay lives like the gay men and women who moved to coastal cities; the Pittsburgh LGBTQ community was constructed locally, and it relied on the pre-existing social establishments of working class fraternalism. The ephemera of club life that Johns left behind are a memorial for the queer community that helped to define queer life in conservative places everywhere. They also serve as a reminder that, in looking at the present, it’s also important to look at the past: images, videos and objects such as those compiled by the Pittsburgh Queer History Project narrate the growth of safe spaces that expanded within the boundaries of a small city, and that world’s steady evolution into the vibrant scene that is celebrated there today.

The pictures above were archived by Harrison Apple at the Pittsburgh Queer History Project. To view the rest and to read more information, click here.

Published June 23, 2017. Words by Chloé Lula.