Inside Berghain’s New Book ‘Kunst Im Klub’

Until fairly recently, the issue of sexuality and space, in which theories of sexuality are reread in architectural terms and architecture is reread in sexual terms, was a glaring absence in architectural theory. The symposium and publication Sexuality and Space organized by Beatriz Colomina at the Princeton University School of Architecture in the early ’90s was one of the first initiatives to correct this omission. Soon after, Stud: Architectures of Masculinity, edited by Joel Sanders for the Princeton Architectural Press in 1996, focused on the role of architecture in the formation of queerness and the architectonics of gay male sexuality. In his introduction, Sanders writes: “Architecture and masculinity, two apparently unrelated discursive practices, are seen to operate reciprocally.”

Undeniably, the essays, images and graphic design of the recent book Berghain | Kunst im Klub call our attention to the structure of a homoerotic look transacted through space. The architecture of queer visibility, which this book covers in detail, troubles the heterosexist perspective by overturning the social rules forbidding male spectacle within public space. Indeed, there are no better “introductions” than Sexuality and Space and especially Stud: Architectures of Masculinity to understand the sexual implications of the architecture and art of Berghain. Berghain | Kunst im Klub, designed by Yusuf Etiman and conceptualized by Kathrin Hain, tells us as much.

The book’s cover is entirely devoid of text, with only the spine featuring the title—a smart and courageous gesture by the publisher Hatje Cantz. All we get is the club’s logo superimposed on an image of one of the club’s raw industrial walls. It functions as a bio-political self-representation of the clubbers, the heavy beats and yes, in contrast to what many say and think, the open atmosphere of Berghain. Or as Berghain regular and photographer Wolfgang Tillmans put it: “The atmosphere in a (good) club is like art is supposed to be: it’s totally open and doesn’t tell you what to think.” Had I therefore also seen on and in Etiman’s cover an abstract rendering of the male anus in Wolfgang Tillmans’ Phillip, close-up III from 1996, which once adorned the Panorama Bar, and which is reproduced in full glory twice in the book?

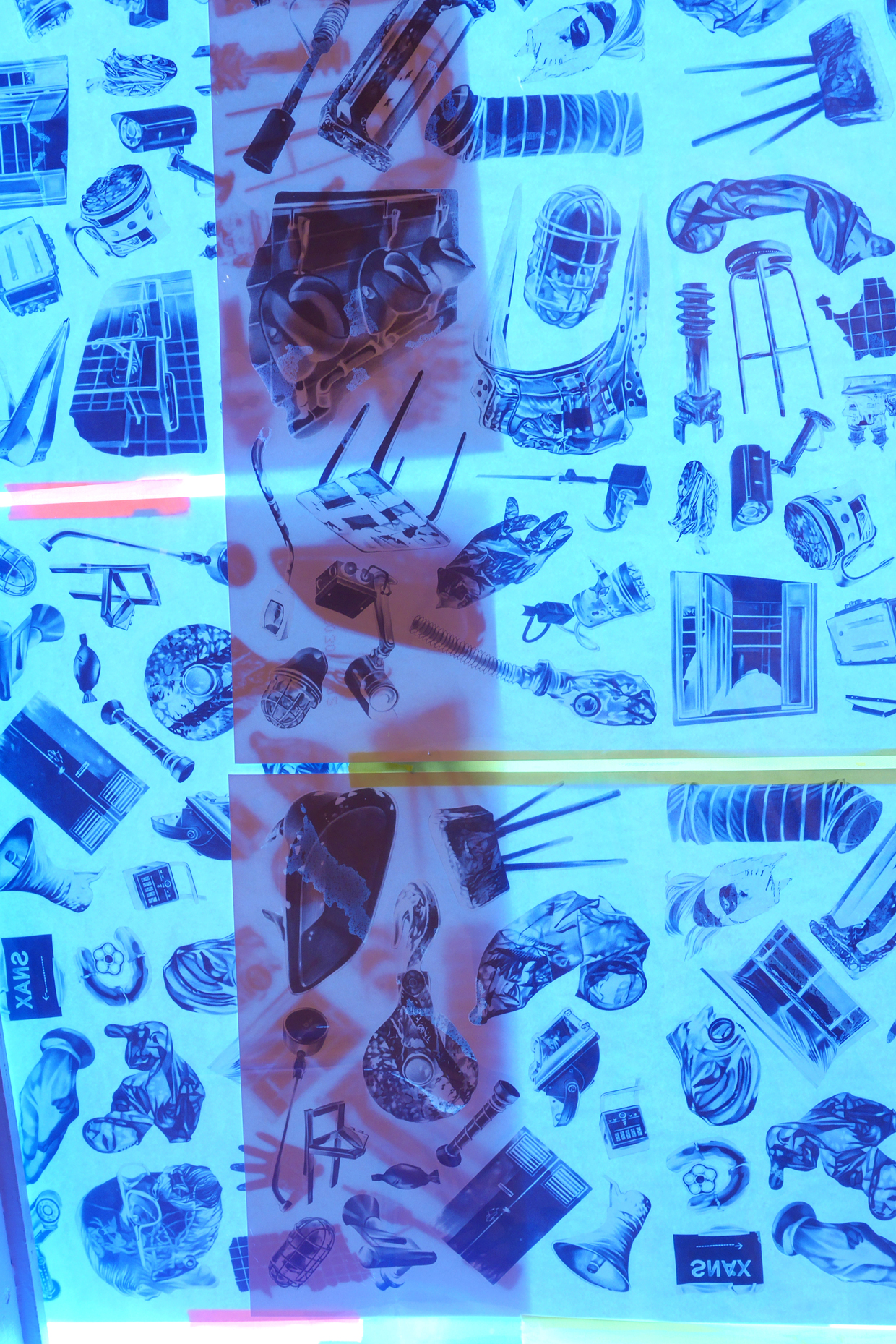

This and the other plates of Tillmans are a perfect introduction to the rest of the book. The interview with Tillmans is intelligent and enlightening, as are most of the other carefully edited interviews. Tillmans ends his interview: “I find the most interesting visual medium at Berghain to be the flyers.” These exquisite flyers are placed at the very end of the book, and I have to admit, they are often more memorable than most of the art, which the book generously and thoroughly documents. That said, there is a fascinating common theme in almost all the contributions featured in Berghain | Kunst im Klub, gleamed not only from reading between the lines. All contributors appear to show and tell of fractals and fractality, fluids and fluidity, darkness and lightness. It makes sense when seeing photographs documenting the art, as for once all the lights are on! Suddenly we see the borders of borderless Berghain. Even photographer and legendary doorman Sven Marquardt discusses the importance of daylight.

As far as fluids are concerned, Sarah Schönfeld’s Hero’s Journey (Lamp) from 2014, an illuminated glass case filled with a thousand liters of urine she collected and preserved in the club’s toilets, is one of the most poignant works on view. The urine shines like the gold in a Byzantine church. It is an image of salvation. Elsewhere he pigeon droppings and dust particles that appear as fractals in the photographs of Friederike von Rauch create the same kind of “otherness”. As argued in the scholarly publications mentioned above, it reminds us that there is no such thing as queer space; there are only spaces used by queers or put to queer use. This book explains exactly that. And it does it so well.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2015 issue of Electronic Beats Magazine. Click here to read more from the magazine. All images appear in Berghain | Kunst im Klub / Art in the Club, published in 2015 by Hatje Cantz. Cover photo: Wolfgang Tillmans, Mundhöhle, 2012. © Wolfgang Tillmans. The work, which translates into English as “oral cavity”, hangs at the Panorama Bar.

Published October 05, 2015.