A Flash of Emotion: Investigating the Psychological Effects of Club Lighting

From hallucinatory experiences to nocturnal terrors

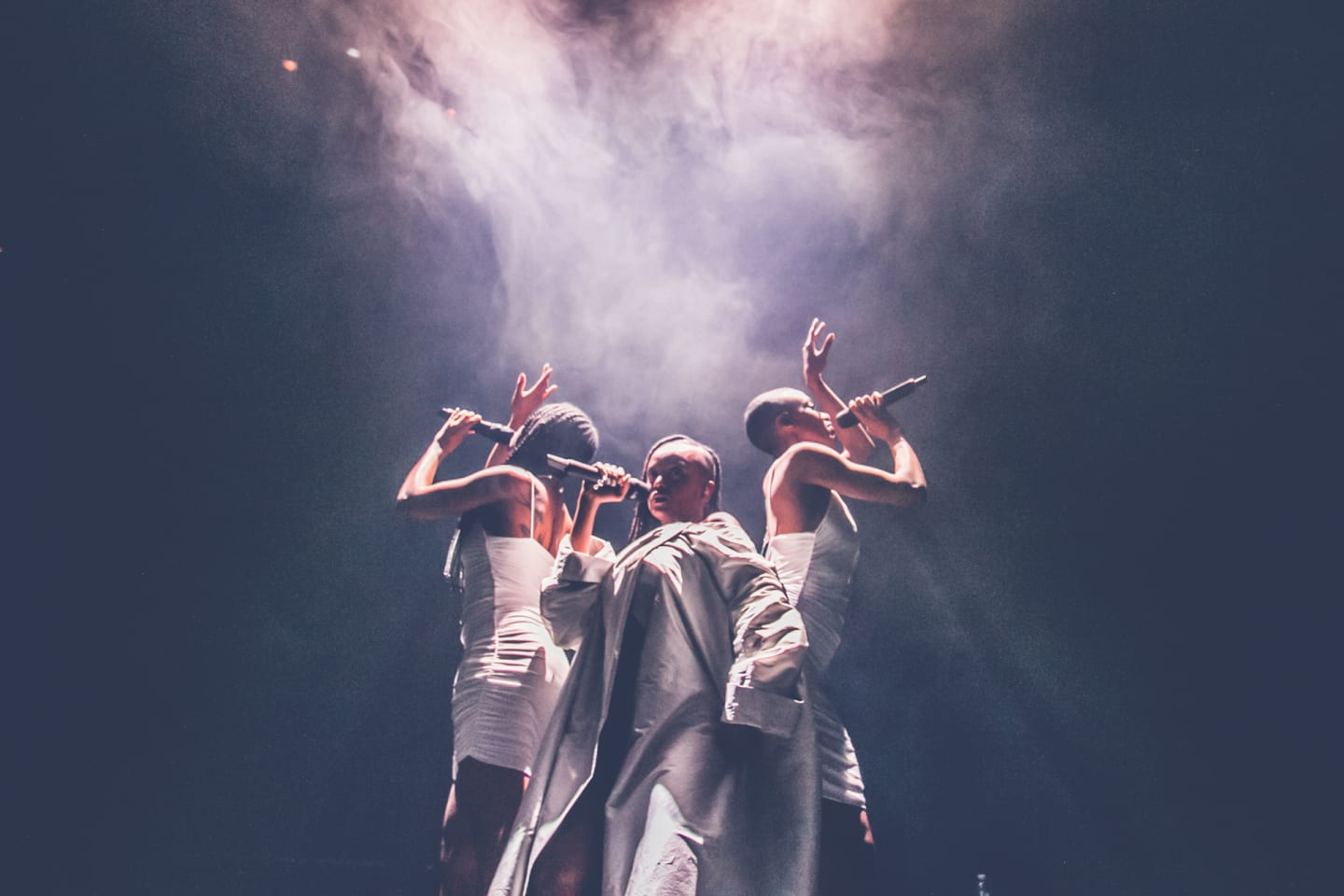

There was a key moment during Kelela’s Take Me Apart concert at Berghain, just before the artist launched into “Better,” when the room suddenly illuminated in soft monochrome lights and subdued shades of gold. As the white smoke engulfed her, she held back tears and announced to the crowd, “This one always makes me cry.”

It seemed her wounds were still fresh from the breakup that inspired her 2017 debut album on Warp. And the color yellow, which signifies positivity and happiness, as well as clarity, enlightenment, and remembrance, conveyed all the conflicting emotional states encapsulated in what was one of the most tender live shows I had ever experienced.

Light is one the most important stimuli for influencing human perception, and it can have a direct effect on the psychological well-being of individuals. Correctly used, a space’s light can be used to communicate specific moods and trigger emotional responses. According to “The experience of nature: A psychological perspective,” published by researchers Kaplan and Kaplan in 1988, “a change in texture or brightness in the visual array is associated with something important going on in the scene […].” In a club setting, this could imply a pivotal moment in musical performance.

“If you dig into [Kelela’s album], it’s deep. She’s singing about a lot of things that are heavy and very emotional, so I wanted to be able to play that drama out visually,” Michael Potvin, the man behind her concert’s color framing, says over the phone from his Brooklyn office. “Amber was a very honest color for this intimate moment, so that the song and its lyrics could shine through, without flashing or other lighting tricks.”

Potvin is the founder of Nitemind, a studio practice specialized in creating “immersive and interactive installations as well as dynamic and performative light shows at festivals and venues.” In its ten years of existence, the studio has amassed a portfolio of lofty clients in the fashion world such as Alexander Wang and Comme des Garçons, visual artist Korakrit Arunanondchai, Marvel’s Netflix show Luke Cage and tech giant Google, but its origins are in nightlife.

In the early 2010s, Potvin was involved in Steel Drums, a now-defunct Brooklyn club that hosted East Coast dance music legends like Physical Therapy, Galcher Lustwerk, Anthony Naples, Max McFerren, Ital (A.K.A. Relaxer) and Aurora Halal. A collaborative friendship with Halal led to Nitemind’s work with Sustain-Release. During the legendary weekender in upstate New York, Potvin and his team temporarily transform a kid’s summer camp into a rave utopia, fully equipped with video-mapped LEDs, lasers, UV light blasting on the grounds’ basketball court and abundant fog machines pumping out smoke surrounding sweaty bodies. One attendee I spoke to recalls having a full “falling through outer space” hallucination in one of the rooms with 360-degree strobes traveling front- to-back and sideways across the ceiling.

In other, more sinister scenarios, the use of light can be instrumentalized for scrutiny and control. At last year’s debut edition of Re-Textured, a UK festival that promised to combine “experimental electronic music, modernist and industrial architecture and innovative lighting,” I found myself crammed into the corner in an aggressively-lit ambient room of London’s E1 venue, with a feeling of paranoia beginning to creep in. The beamer projecting video art in the “chill out room” was so bright that it felt like it was being used to monitor people’s behavior in the space in order to prevent them from (or to catch them in the act of) taking drugs. This was only enhanced by the group of security staff shuffling around the room.

“One of the biggest challenges [in a club setting] is to make sure that it’s dark enough,” says Veslemøy Rustad Holseter, (A.K.A. Grinderteeth). As part of her involvement with the No Shade collective, she trains femme, trans and non-binary folks to become light technicians. Since September of last year, she’s been in charge of the visuals at Trauma Bar und Kino, a multidisciplinary performance space in Berlin. With their progressive arts programming, Trauma has quickly become a vital part of the city’s nightlife, creating a blueprint for alternative clubbing. As a musician herself, Holseter understands how certain colors enhance the audience’s experience. In her teaching sessions, she compares her practice to cooking. “You have different spices, different things that you can play around with. To me, it’s important to enhance the mood of whatever is playing by working with contrast.”

In her work, Holseter enjoys bathing the room in color washes of fluorescent reds or greens. “For me, it’s all about enhancing the mood, so obviously if the mood is harder, I will use stronger colors. Then, if it’s softer music, I tend to use softer tones,” she says. Specifically for club nights, she might use a combination of red and white, which lend themselves well to a techno set, whereas in a concert setting she might use amber, golden shades, or lighter blues.

The color amber also played an important role in SKALAR, the acclaimed collaborative installation between light artist Christopher Bauder and techno producer Kangding Ray. The project sought to “explore the complex impact of light and sound on human perception.”

Originally premiering in Berlin’s impressive Kraftwerk building during CTM’s 2018 edition, the installation used 65 kinetic hanging mirrors, which reflected beams of light across the 100-meter space. This evoked feelings of warmth and comfort despite the space’s vast, cool structure. With light, movement, and sound, Bauder says, “you can generate very profound emotional reactions in the audience and, of course, play with it.”

Bauder is particularly interested in the psychophysical component of technology. SKALAR, he says, pushes audiences towards a state of serenity when the light replicates sun beams or moves like an underwater creature. In another moment of the show, viewers have reported feeling ominous and anxious when the visuals morph into “a monster trying to attack you.” However, he explains, “in reality, nothing is happening except light signals moving across a room.” Rather, these reactions are triggered because “you have these abstract associations due to basic human stimuli.”

Projects like SKALAR and Deep Web, another installation Bauder worked on with musician and sound design pioneer Robert Henke, combine cutting-edge technology and a kaleidoscopic aesthetic to achieve a world-building effect. While SKALAR’s halcyon light beams immersed the visitor into a hallucinatory natural ecosystem, Deep Web’s take on the interconnectedness of digital communication and its surveillance tactics painted a more somber picture, employing hyper-modern technologies like computer-controlled kinetic elements and laser systems to convey this message.

Like Bauder’s ingenious kinetic light installations and Nitemind’s lustrous underground vision, lighting is also a guiding aesthetic principle for Dixon’s Transmoderna residency in Ibiza. Last season, Transmoderna placed an angular mirror sculpture designed by visual artist Heleen Blanken in collaboration with Thijs Rijkers above the DJ booth, sending shards of color across Pacha Ibiza’s gargantuan dance floor.

Today’s boundary-pushing lighting techniques may diverge in their applications, but their intentions remain the same: all intend to shift the attention away from the selector in front of the decks and towards the overall dancefloor experience.

“I believe that dancing with your crew, your girl, or that other person you’ve never met before is a key part of clubbing,” Dixon says, “Lights around the DJ work great for certain moments, but it’s not about showcasing his or her hand-movements for 6 hours a night.” He believes that there is a thin line between entertainment and distraction, and if a club’s lights are only used to glorify the DJ, then it becomes a superficial show.

By loading the content from Soundcloud, you agree to Soundcloud’s privacy policy.

Learn more

Potvin of Nitemind agrees. “People want to lose their minds and be somewhere else for a change,” he says. “They just want to be in the dark—and be with their friends.”

Luckily, today’s club culture provides space for functional approaches to light design as well as forward-thinking tech to evoke intense, dynamic moods. Whichever philosophy one subscribes to, everyone can agree on one thing: the emotional response must come first.

Published February 08, 2020. Words by Caroline Whiteley, photos by Ant Adams & Ralph Larmann.

Follow @electronicbeats