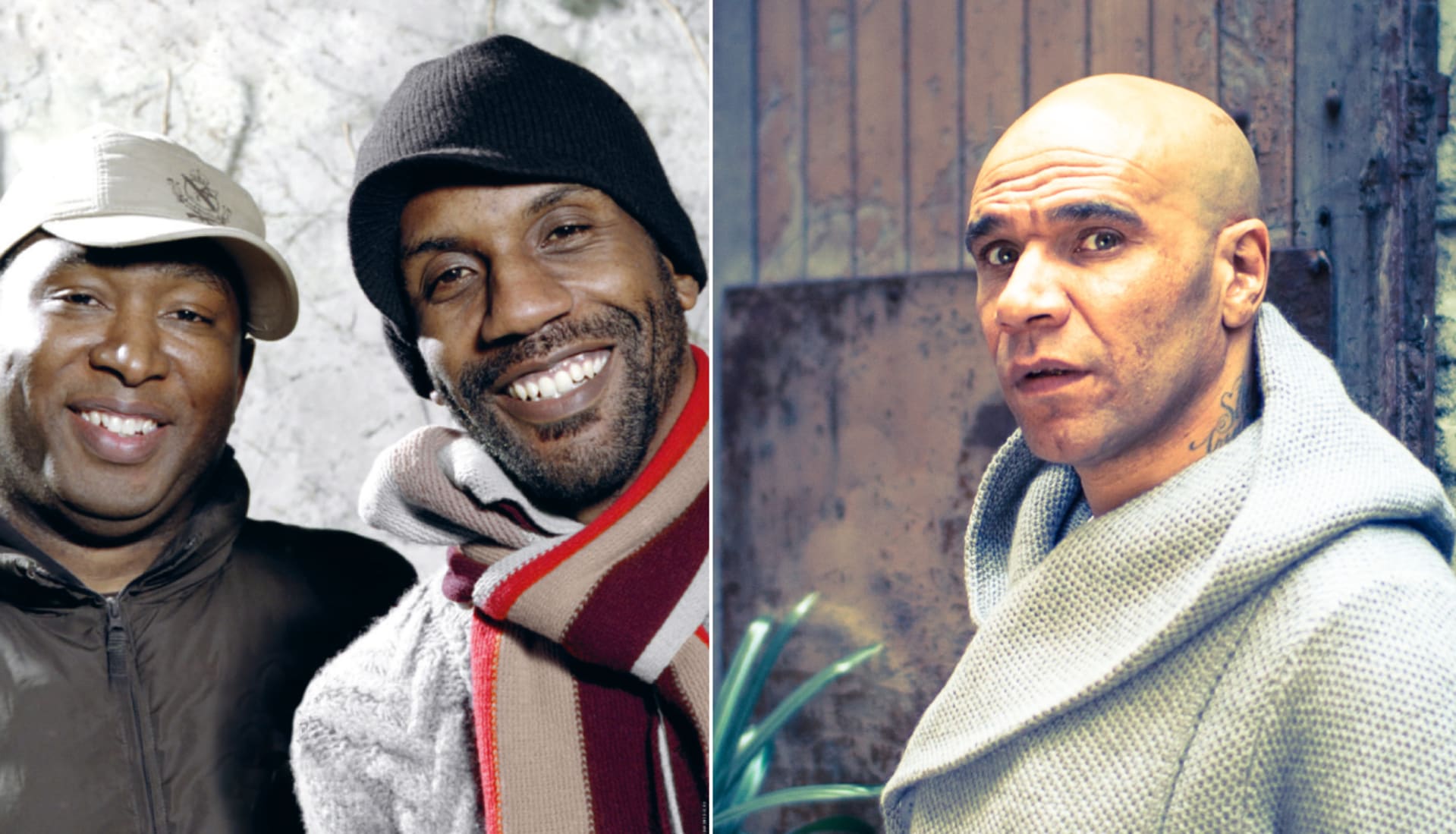

Mentors: How 4Hero Programmed Goldie’s Software

In 1988 I arrived back in the UK. I had been living in New York and Miami for a while, working on graffiti projects and getting saturated in the subculture there. Upon my return, I didn’t move back to my home town in the Midlands. Instead, I stayed in London with a guy called Gus Carl, who had been the camera man for the graffiti documentary Bombing, which featured a chunk of my work in the UK. He had a quite famous place where I spent my time painting.

I went to Camden a lot to check out the scene. It was the time of acid house and the crossover from indie to rave. It was all new to me. One place I’d go to a lot was the Wag club, a famous hotspot. It was kind of the overground, but in the underground. The Brain in Soho was another club I went to. People at the Brain would say, “Listen, you need to go to Rage.” At that time, I had just started to date [the late DJ] Kemistry. I had tried to ask her out for a while, until one day she said, “Look, I’ll go to Rage.” And that was it for me, really.

People know the story; I went to Rage and it blew my mind. Kemistry then took me to another club called Astoria, where 4Hero were doing a PA that night. Dego and Marc were on stage with Ian. When I saw this shit I was like, “That’s what I want to do.” I pulled Marc to the side and I gave him my number and said, “Look, I do a lot of artwork and stuff, I wanna work with you.”

Shortly after that I went to their studio in Dollis Hill. The first thing I did was redesign the logo of their label, Reinforced Records. That was the beginning of our relationship. Those guys, they wasn’t really going out. Marc was kind of into the whole sound system thing and Dego wasn’t really going out clubbing, either. But I was. I was in the thick of it.

Marc and Dego basically programmed me. We always have this running joke where I phone Marc up, sometimes randomly, and say, “Listen, I need you to switch me off, man.” And he would say, “We programmed you—you’ll never stop. You just keep engaging your own software.” A bit like the scene from Blade Runner. It’s a really personal thing with them, especially with Marc. I cut my teeth with Reinforced.

I really wanted to work with them and proposed to put an EP together. I’d already done a collaboration with a guy from Iceland who was influenced by breakbeats and rave called the Ajax Project. It was a four-track EP, which was a white label, and once I started seeing Kemistry I produced this record. You know, I went to the pressing plant, got them pressed up, put them in a car and drove them to Moles Music in Tottenham. They all sold out; we repressed. When I suggested to put an EP together for Reinforced, Marc had already heard of the Ajax Project. He said, “You’re the kid who did the Ajax Project.” And I was like “Yeah, I wanna do something different. You guys’ sound is incredible.” I said, “Look, just give them the money for the fucking studio. I’ll put half, you put half.” At that time, putting 750 pounds into a kid going into the studio was unheard of. But they believed in me. Marc was like, “Let’s just do this.”

I had these overground ties with people like Mark Rutherford, who went on to produce Peter Gabriel. At the time he was working at William Orbit’s studio [who later produced Madonna]. He knew me from the Wag club and all those trendy London hangouts. I went into the studio with him and a friend of mine, Linford Jones. We were the originators of the Rufige Kru. Linford had a great record collection, so I would be like, “I want this part of the record, I want that part of the record.”

So basically what happened was we hired in two Akai S1000 samplers. Now at that time, they said to me, “You only need one,” and I said, “No, I want two.” I literally fucking filled them up with samples, completely. No memory left. And they were like, “What the fuck are you going to do with this?” And I said, “I’m gonna put it together.” I was very stocky at that time. I filled up everything. Because I already had that graffiti mentality, I knew the sketch, I knew the outline.

The first thing we did was the Krisp Biscuit EP which was a 12”. That went really well, and then we went back and did “Darkrider”. When I took it to Reinforced, they were fucking blown away, and after that I really started to work with them. I would be there with Dego in the daytime and then when Dego would finish at 4 p.m., Marc would turn up after work and we’d continue with the same tune.

Because of the success of my first records I felt comfortable being in the studio with Marc and Dego. Before that, I could’ve gone into the studio, but I wouldn’t have held my own. Because of my b-boy mentality, I wanted to be standalone to begin with to see if I had the nuts myself. I pulled it off with engineers that weren’t used to that particular type of music. They didn’t know about 1-fucking-55 bpm—they were all about 90bpm.

I had a lot of ideas and samples in my head and Marc and Dego would listen to what I said. We went into these intense sessions of cutting up breaks, recording them to DAT, resampling everything onto the computer and layering stuff. Because for me, I was making colors. That was my approach: let’s make the colors first, and then we’ll do everything else after. it was about eccelecticism. Like a graffiti writer says, “This is an outline. I’m gonna show you what colors you’re gonna use, and then we’re gonna fill it in together.” Put blue there, put pink there. That was my attitude toward music.

It was also based on b-boying. It was about transitions. The transition between 16 bars to the next 32 bars to the next 64, back into that middle 16—the transitions were what I was about. How can I move from one thing to another? How does a b-boy do a breakdown smooth? He doesn’t fall out the fucking move, he continues the move. How can you go from a windmill to a fucking headspin and not fall over? You can’t do that, right? Because you look shit. You look fucking shit. You have to finish the move. Now the move you finish with is only a very small, significant move that you’re doing, but that’s what the style aspect is. How do you get in and out? How do you make it look like it’s no effort to do that? That’s the trick!

So within the music it became the same thing. It would be eclectic for a while—32 bars, 64 bars—and then you’d pull a fucking move within the music, that would be a very big move, whether it was a sound that came in, or a drop that would be kind of elaborate with a vocal. I would get stuck in an arrangement and Dego would be like, “Just try this—just try different things.” It was about transitions. It was always about going from one high plane to another to another. And that’s what I brought with me. Marc always says that I always had a clean idea of what I wanted to do. And it kind of added to the whole Reinforced mentality.

Then this opportunity came along where Synthetic Records wanted to give me 10 grand to do an EP, which was a lot of money at the time. They actually offered me a two-EP deal. I told Marc and Dego, “Look, I wanna do this with these guys.” Reinforced gave me their blessing and that’s when I went into the studio and did tracks like “Terminator”, “Kemistry”, “Knowledge” or “Sinister” with Mark Rutherford. This is the bastard child of fucking big studios man. As a parting gift I gave Reinforced Records the “Terminator” remixes. By that time, I was like “Fuck it, I need to do my own label.” That was the beginning of Metalheadz.

There was never a time where it was like, I’ve outgrown these guys in any way. It was just that they knew the Terminator EP and the Angel EP were going to be big. Marc always said that when he heard those EPs, everything we’d learned together, we’d just gone to another level. And Reinforced as a record company knew that they couldn’t do me justice. Marc said that in his own words. He said, “This is bigger than all of us. We need to get this out, because that’s gonna be good for all of us.” Marc and Dego recognized that. So when we parted ways it was like hugging your brother at the door, like sending a school kid out and the father going, “Go on, kid, you’re gonna be okay out there, man. Just go and do some fucking damage.” And Mark and Dego knew all that. They fucking programmed me. They are the guys who taught me everything I know.

Read our conversation with Dego and Harris Elliott and check out more Mentors columns here.

Published February 26, 2016.