Nazar’s Final Battle Cry

Although his debut album Guerrilla shoulders the weight of wartime trials and tribulations, the Hyperdub artist finds a true sanctuary in storytelling.

Nazar was just seven years old watching the television when the news anchor suddenly announced that his father and namesake, Alcides Sakala Simões, had died. Living in Brussels, Belgium at the time, he remembers his mother screaming for him to be taken to an adjacent room and his sisters crying as they continued to watch the broadcast.

Simões was the Foreign Affairs Secretary for UNITA (the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola), an anti-communist party that fought against the reigning political power, the Soviet-backed MPLA (People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola). The UNITA chieftain Jonas Savimbi sent Simões, his right hand, to the guerrilla party’s headquarters in Jamba, a town just north of the Namibian border, to divert the Angolan government troops during a final battle in 2002. It was an assignment to which he would sacrifice his life.

His father recounts this story in his native tongue Umbundu on “Diverted,” the second track off Nazar’s debut album Guerrilla, released on Hyperdub Records. On the record, the 26-year-old producer, who moved from Belgium to Angola at thirteen and is currently based in Manchester, combines churning layers of drones, cocking guns, and leaden drums characteristic of his trademark “rough” kuduro style. In doing so, he evokes the psychological struggles with mortality that Simões underwent at the Jamba base. However, in the end, it wasn’t he who was killed, but Jonas Savimbi, the man he fought to protect. Government forces believed Simões had died alongside Savimbi, and incorrectly reported his death to the media. By acting as a martyr, he had unknowingly saved himself.

“Diverted” sets the tone for Guerrilla. It is at once a story about Simões’ diversion to Jamba and also Nazar’s own sojourn to Brussels, Belgium, where he stayed with his mother and sisters in asylum during the final years of the Angolan civil war, which spanned from 1975 to 2002. “The album always draws those connections between me and my dad, even though we were separated, but we still dealt with many similar experiences without even being together for that long,” he tells me.

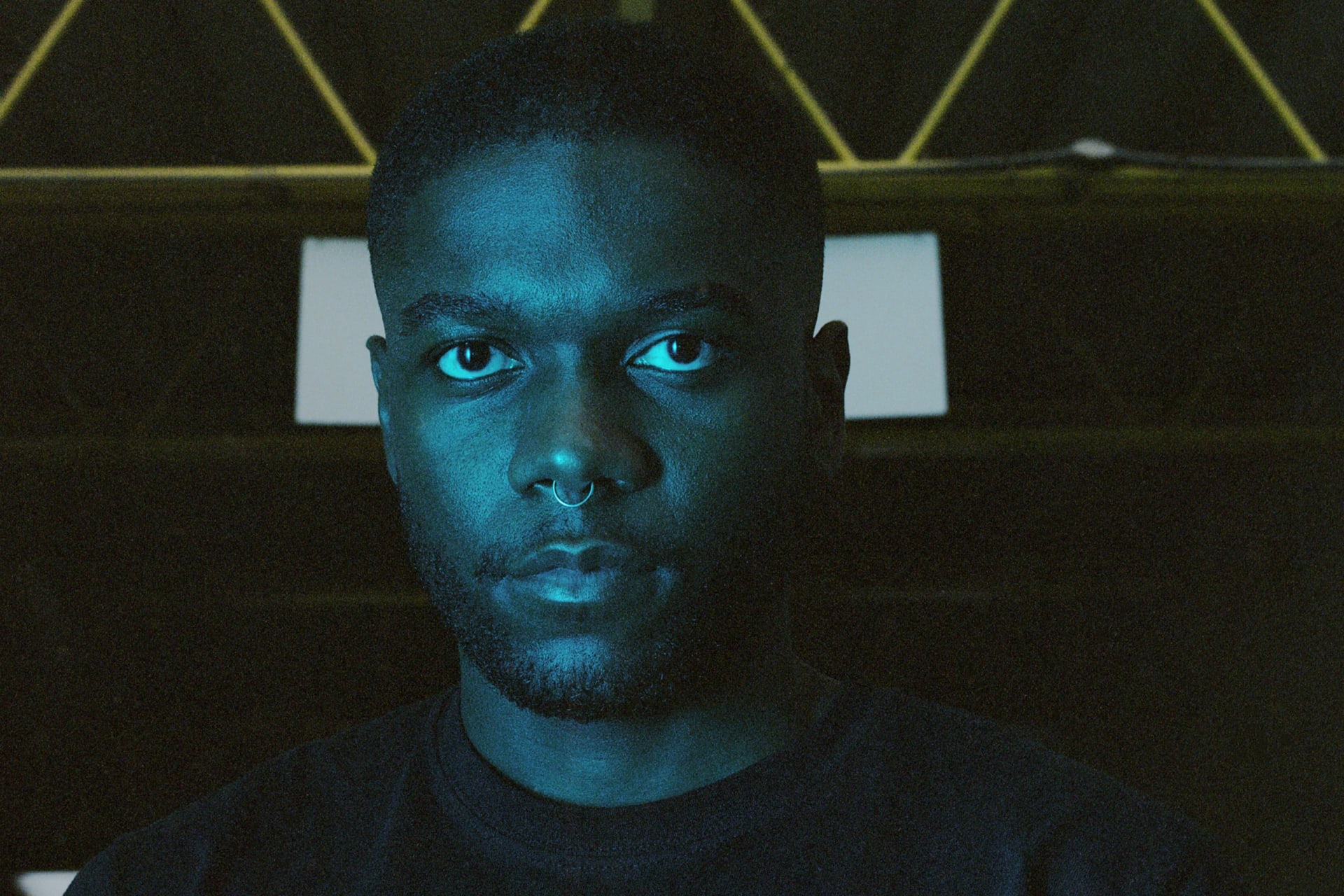

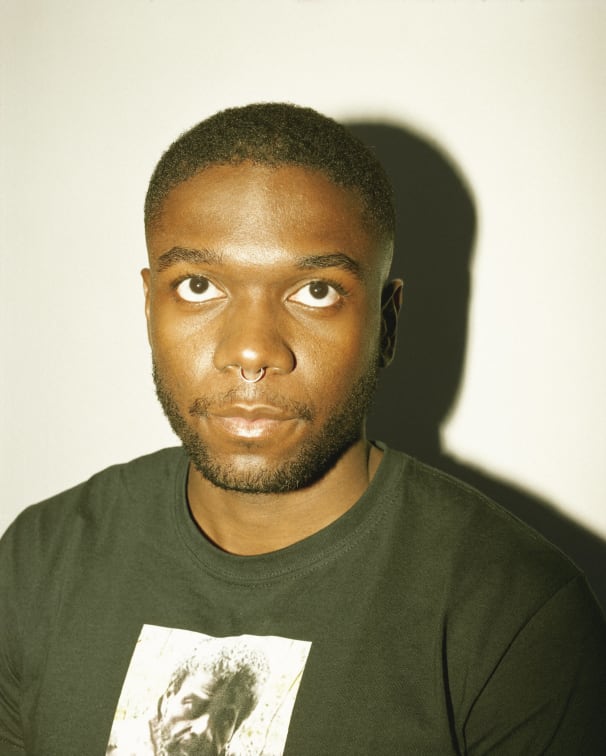

In person, Nazar has a pacifying presence. Even when he’s retelling the climax of another harrowing incident, he speaks in hushed tones with an ambling, unhurried pace. Today, he wears his own album’s merchandise, a black shirt with an image of his father’s stern face embossed across the chest. Oddly, it almost feels as though I’m interviewing the two of them at once.

“Diverted” is so significant because it hones in on the parallel experiences of both father and son overcoming fear and isolation as they faced their respective unknowns. But, even more so, it represents Nazar’s act of retracing geographical and emotional chasms to understand his father.

During the process of producing his album, Nazar consulted with his father’s published journal Memorias de Um Guerrilheiro. Flipping through its pages and seeing each date, time, and location where his father thought about him, “I could finally understand that he used these thoughts as strength to keep going,” Nazar says, “I was getting finally answers that I never had before, especially feeling whether he truly loves me.” That’s why, he continues, “Even though the album is for my family, it’s more about my dad because I’m just trying to fill the gap that there is between me and him.”

Guerrilla is replete with these tangled personal and historical wartime narratives. “Bunker,” for instance, references the three days between the first and second rounds of reconciliation elections after the civil war on October 30, 1992, when the MPLA launched an overnight assault (known as the Halloween Massacre) on thousands of political officials and voters related to the party’s opposition in Angola’s capital city Luanda. Nazar’s family escaped to Hotel Trópico, a place that provided temporary refuge for foreign journalists, but the regime killed his uncle in the attacks. Another, “UN Sanctions,” references the travel bans and arms embargoes implemented by the Security Council on his birthdate, July 15, 1993, against UNITA to encourage peace negotiations between his father’s rebelling party and the Angolan government.

Where his previous Hyperdub EP, Enclave, activated kuduro as an all-sweeping sonic insurgency—a sort of blistering, fists-up protest against political subjugation—Nazar’s newest work finds its power by collaging the moody nuances of textured vocal samples and gently exhaling melody lines—most prominent in “Mother”—between the rhythmic contours of his more truculent compositions. “It wouldn’t be realistic to have an album only about aggression,” he explains. “Not all moments were that harsh because there were times where you could find peace. There were times when you would forget. War was basically just a way of life.”

As conflict waxed and waned in the continent over, Nazar spent his childhood in Brussels with his mothers and sisters listening to kuduro—which was on blast during house cleaning sessions as a “way to just still feel connected to the motherland.” His family would listen to festive classics like “A Felicidades,” which translates to ‘happiness,’ by Sebem when they felt homesick in the diaspora. But songs like these had a sparse, dated beat from an older generation, and it wasn’t until he moved to Luanda at thirteen years old to reunite with his father when he discovered the wealth of kuduro subgenres. “The first thing that I noticed during the ride from the airport is that it’s impossible not to listen to waves of frequencies. All the cars had these powerful soundsystems shaking with heavy batidas,” he remembers.

Then, as a new student in private school, Nazar further developed his interest in production through observing his classmates. He recalled, “Sometimes they would make beats with the table, do a kuduro freestyle, and another one would just dance.” The desire to assimilate pushed him to download a cracked version of Fruity Loops and finish a fresh track every night to show off to his peers the following day.

Originally, he modelled his sensibility after the French touch of Daft Punk and Justice, his idols at the time and from where he took his artist name Nazar, after the song “Waters of Nazareth.” “But after I was fitting more into the Angolan society,” he says, “my styles would shift.” At one point, his bedroom experiments within both rhythmic kuduro and European industrial electronic music merged, eventually dovetailing to become his signature sound.

Nazar’s coming-of-age trajectory has shaped him in other ways, too. Guerrilla may be the best example of this. The album was already incubating nearly a decade before its production, deep within Angola’s central highlands.

About once a year, since the age of fourteen, Nazar and his family would take a twelve hour pilgrimage through grassy, windswept terrain and across precarious roads encircling the Bié Plateau to the rural town of Bailundo. Compared to Luanda, a city that Nazar describes as “some type of island where you just don’t acknowledge how much suffering there is outside,” Bailundo provided a flitting glimpse into other walks of life.

Here, the electricity was shoddy at best, and Nazar had to shower with bowlfuls of water. But, as the humble birthplace of his father, it presented the rare occasion to sit down, drink kissangua (a traditional beverage made of fermented corn flour and water) and connect with his distant relatives. For hours and hours, his family members would take turns regaling one another with elaborate accounts from the 27-year civil war. Often, Nazar’s father would flip his near-death airstrike experiences into a string of irreverent tales doused heavily in black humor.

As Nazar grew older, he began noticing a pattern. His family would visit the same person six months later, and they would recite an identical story, except with progressively more and more details. He says he deduced that each retelling must have been an exercise in navigating trauma. And, through such candid processing, it also became an interfamilial exchange of knowledge. “What they would do,” he explains, “is the oral passage of narrative testimonies to the younger generation, to me, so I can know where I’m from and what we’ve done, and what type of person I want to be.”

Guerrilla represents Nazar’s turn to speak amongst his elders. Through its prismatic emotive qualities, the album encapsulates motifs of African diaspora, paternal absence, postwar recovery, and human resilience within an accelerated, electronic context. If art functions as a tool to immortalize its creator, Guerrilla is an expansion of personal mythology that grows stronger with every repetition.

Nazar’s Top 5 Coming of Age Tracks

A sentimental selection of tunes that made Nazar the man he is today.

Os Lambas – Comboio 2

A classic, and perhaps the most important kuduro song of Angola’s history. This song showed us how maximal and textural the genre could be. It’s still the most played song in the country. There’s no party over there where this song isn’t played at least once over the course of the night.

Justice – Water of Nazareth

This song amazed me in my teens. I wanted to explore noise because of all the texture and blown-up bass–all codes that were present unintentionally in kuduro for many reasons. One such code is the inaccessibility of the genre’s producers to acquire gear of standard quality, which led to distorted kick and bass and, therefore, heavily influenced the genre’s sound. Also, there wouldn’t be a Nazar without Water of Nazareth. I took my name from this.

Actress – Jardin

One of my favourite tracks ever. Just blissful. It’s the type of song that could be looped forever and ever. It inspired me to make the song ‘Mother’. I want to be able to compose something just as beautiful.

Mount Kimble – Maybes (James Blake Remix)

This song brought me the most colors when I listened to it in moments of darkness. I teared up a lot it because of how euphoric and amazed I felt by having these sounds in my mind. It influenced me to balance more the melodic aspect of my songs and experiment more.

SebastiAn – Tough Games

SebastiAn has always been one of my inspirations. I’ve learned a lot through the way he “cuts” his best. You can hear all the information inside working together to make a groove out of the instability. This element is also very present in my “rough” kuduro tracks.

Published March 13, 2020. Words by Whitney Wei, photos by Amber Pinkerton.