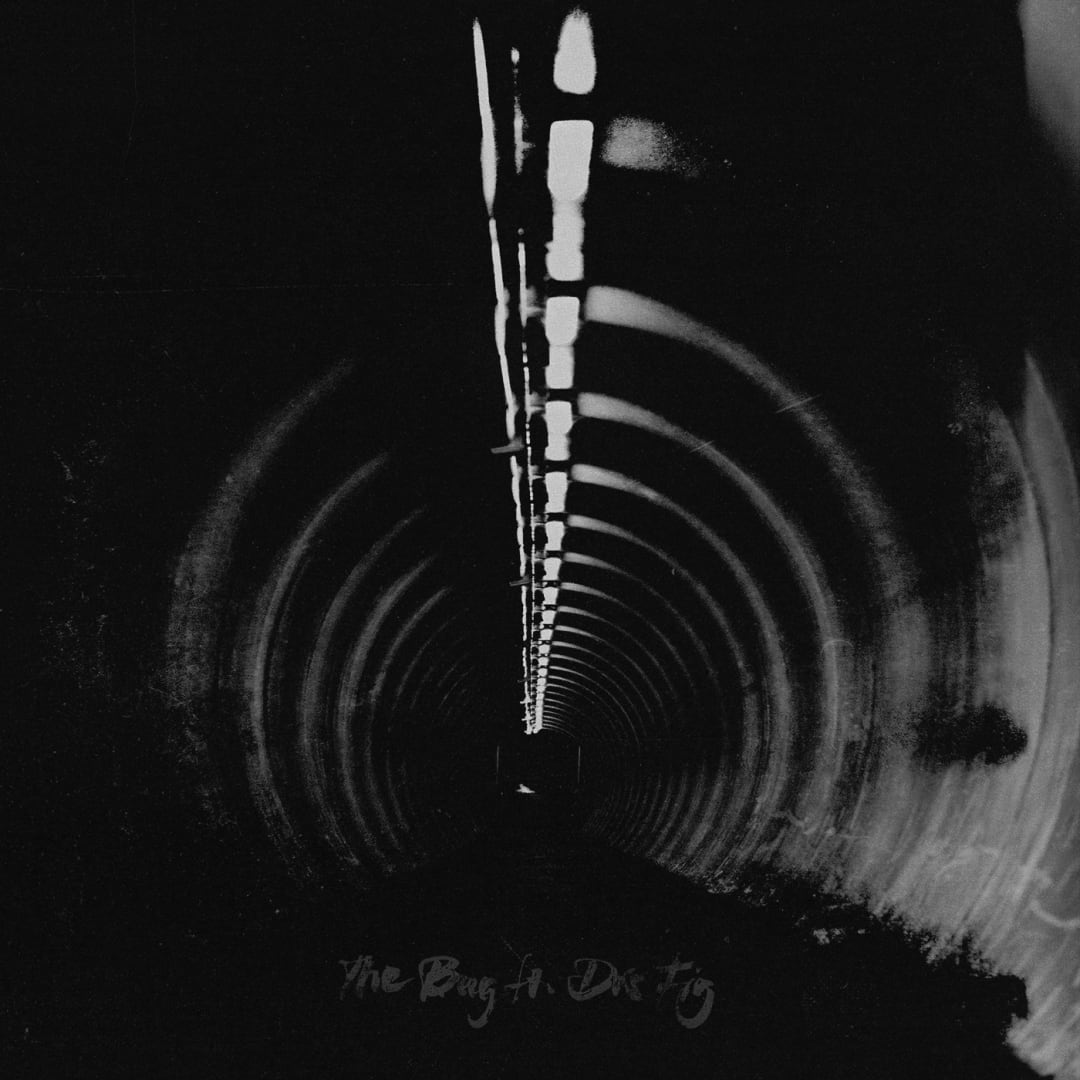

The Bug and Dis Fig on Mutant Dub, Soundsystem Culture, and ‘In Blue’

Podcast host Chloé Lula interviews The Bug and Dis Fig about their collaborative album for Hyperdub and the roles that dub and sound system culture have played in their careers.

Last December, The Bug (real name Kevin Martin) and Dis Fig (AKA Felicia Chen) released In Blue, a collaborative album that sounded, at once, like both of their collective sonic worlds and like nothing either had released before. Through the combination of Martin’s narcotic dubbed-out rhythms and Chen’s soothing yet haunting vocals, they created a dread-filled, subterranean aesthetic that they’ve since coined “tunnel sound.”

In this excerpt from an upcoming episode of the Electronic Beats Podcast, moderator Chloé Lula talks with the duo about the album process, diving into their disparate experiences with dub music and sound system culture growing up on opposite sides of the Atlantic—and how they coalesced to provide an eerily fitting soundtrack to modern isolation.

(This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.)

By loading the content from Bandcamp, you agree to Bandcamp's privacy policy.

Learn more

Chloé Lula: Can you just tell me a little bit about the process of putting it [In Blue] together? I’m curious about the vocals. Did you write them all yourself, Felicia, or was everything a collaborative effort between both of you?

Dis Fig: Kevin sent me, initially, a bunch of the demos that he had made for his Solid Steel show. We didn’t really even plan on doing an album. It was just like, “Okay, send some tunes. See if it works.” I was going to try a few things on them, and in the end, I guess all the vocals were written by me, but I would send him some demos and we would talk about what kind of feel we were looking for, what the ethos of the album was. Then eventually we started just collecting a lot of tracks, and we had enough for an album.

CL: The album is interesting to me because it feels like a very natural confluence of each of your respective influences and past works. I would venture to say that you’re also a natural pair because you both make music that’s non-conformist and unconcerned by commercial standards, and that maybe skirts around this idea of outsider-ness that I’ve glimpsed in both of your respective releases before this.

The Bug: Yeah, I’d say that as I’ve got to know Felicia more through the making of the album, there’s definitely, probably, a lot of shared life philosophies and aesthetic approaches. I think as far as I was concerned, when I approached Felicia with the proposition of collaborating on this album, it was because I felt that we were trying to make something original, and her voice was fresh. I really liked what I heard and felt that it was the voice in my head that I’d been looking for, the style of singing that could fit hand in glove. Because if I’d put a dancehall MC on these rhythms, people would probably say it was an aggressive album.

It’s funny because someone literally today was dissing me on the public forums saying that my new music’s too girly. That put a big smile on my face, and this is a fan. When I was trying to decide what to do with this big batch of rhythms that I’d had in my pocket, really, I knew that I didn’t want the album to conform to a stereotypical Bug record. I knew that I was looking for something that would alter the emotional impact yet aware that it had trademark Bug-isms. But I felt that when I heard Felicia’s voice, somehow I knew that, yeah, actually this can steer in a direction that could really be something out of the ordinary. And again, that just appeals to people’s imaginations. That was planned, of course.

CL: I know you two have described your work in In Blue as “tunnel” music. Can you elaborate on what that means?

The Bug: It’s just the term that occurred most often when we would be speaking about it. When I first sent the rhythms to Felicia, I said in a way, these rhythms are repetitive, linear, and I’d like to keep them like that. And I’d like to keep a themed mood throughout the record that has a definite, singular aesthetic. I think I remember banding around at the time was this is a sort of… I’d like it to be a record that it’s not an up-front club record. That’s a record that when you come home from a club, you just immerse yourself into. When you’ve still got a vibe going, but you’re not going to be bouncing off the walls.

I think that [it’s] something very nocturnal, something very urban, but yet something very sensual, paranoid, and claustrophobic. Those sort of terms that got bandied around ended up just becoming this repetitive mantra of “tunnel sound.” As we discussed, the musical and lyrical themes, it became more and more apt, really. It probably helped me. I don’t know if it helped Felicia, just to frame what we were doing.

Dis Fig: I think for me, I really did take the sonic idea and pushed into another level in terms of thinking about the lyrical content. I think for me, “tunnel” was really visual. Going along with the sonics, it was a thick haze, where you’re kind of floating and levitating and being pushed around. And yet as Kevin said, completely claustrophobic but then, at the same time, expansive. Going with the lyrical content, I think a lot of it touched on feeling trapped and just being spun around by different things, whether it was relationships or government control and not being able to have your feet on the ground. But at the same time, being able to still have yourself and know that you’re okay coming out of it. And I think that is actually really relevant to these times.

The Bug: There was a sense that we wanted it to be absolutely immersive, not explosive. It was very much the scheme that we came up with. It should literally be about the journey. It shouldn’t be about reaching an end point or where you come from, it’s just being disoriented by the journey you’re in psychologically and musically.

CL: You mentioned you didn’t want it to be like a typical The Bug project. It’s definitely not a stereotypically dubby album, but it does definitely have some like heavy layered low end that evoke some of the bassier textures that you would hear in dub. I wanted to ask you a few questions about dub and dubstep just because these genres have undergone a lot of changes since you’ve first started out. I was wondering if you could pinpoint the ways in which the genre has changed and maybe what aspects of the original sound you helped pioneer are still intact and what’s different.

The Bug: I mean when we discussed with Hyperdub how we felt the record was for putting together a press release, we see it as a sort of collision or a meeting of deviant dancehall, electronic dub, and melancholic soul music. For me, the heart of dub still beats strong on this record. When I think of dub music, I think of more than it just being a sales terminology or a “low comm denom.” I put together a compilation many years ago for Virgin Records called Macro Dub Infection, and I wrote extensive sleeve notes where I drew upon other arts, where I felt great artists, whether it be William Burroughs with his cut-up techniques, whether it be Goddard with his editing techniques in movies, whether it be painters or writers who use dub as a way of thinking and a way of navigating the world, and finding a vision to understand the world around you.

Because, in a way, I think that dub is a way of thinking more than just the obvious baseline effects. And for me, I guess when you look at what we try to do with the record, sonically, it’s not just a probe of deep space in an audio sense, it’s a probe of inner space psychologically. When I think of the best dub music, it feels like you know it, but there’s always an alien unknown quantity and quality in it that is really appealing to me. It leaves a lot of space for the imagination to explore. At the same time, a lot of my favorite dub productions, classic ’70s productions by Scientist or King Tubby, had a sort of a hazy, misty, wall of effects, reverbs, and delays, which again is very much at the epicenter of this record.

For me personally, when you ask me about the way that dubstep’s mutated and my influence if any on that scene, I was always really a bit of an outsider even within dubstep. It was Steve Goodman (AKA Kode9) who interviewed me for XLR8R Magazine after my Pressure album came out, who said to me—just after we finished the interview, and we ended up chatting for quite a long period of time because we had a lot in common—”Why don’t you write at 140 bpm and I’ll play your stuff out at these new parties that we have started up,” which would become DMZ much later on.

At that time, I didn’t even have the term dubstep. I think it was a journalist, Martin Clark, that came up with that term, or it was someone at XLR8R who came up with that term later on. In all honesty, and this sounds crazy, particularly working in club music, I’d never ever thought of a tempo when I made music, whether it be early Bug music or Techno Animal or any music I’d done prior to [that]. I’d never once thought of a tempo because I’d never operated as a DJ. I’d operated as a producer or musician. So for me, the idea of making music to a given tempo was sort of a bit mad and a new way of thinking.

I started making Bug rhythms at 140 bpm and then giving them to Kode9, Loefah, and Mala. In particular Kode9 and Loefah, they were the ones dropping them at early DMZ parties, and I was in the audience or hanging on stage with them, watching people go mad. Yet at the same time, the Croydon crew and a lot of the South London people involved in that scene were younger than me. They’d come from jungle primarily or hip-hop or various other forms of club music, whereas that wasn’t my path. It was almost, you can’t call it a coincidence because dubstep had an impact on me too, and I made great friends.

A lot of the people I’ve just mentioned and a lot of the other people involved in that scene were incredibly friendly and passionate. And it was a joy to be in and around that scene. But at the same time, when I was going down to DMZ, that when it was at Plastic People, before it went to Mass, the parts of the nights I was enjoying was when Roll Deep MCs would come down and grab mics on top of those rhythms. And at the time dubstep was blowing up. I was going to sort of Grime parties really because I like the intensity and the fire of MCs with twisted rhythmic music.

At the same time, I would be going to dubstep parties pretty regularly too. But I wanted the best of all worlds. I was quite greedy. But I have to say even then until now, I’ve never really kept tabs on dubstep as a scene. I think at that time it was really interesting because there were no rules. So you could have the breadth of people like Kode9, Digital Mystikz, Burial, and Shackleton—and people are talking about me in that breath too—at the time. It was quite an extreme range whereas it seemed to become narrower—like most music forms do, once they’re labeled and commodified. They become a bit less imaginative and a bit more consumer-friendly, which is always going to be a bit of a turn-off for me really.

So as per normal, I generally go with my instincts, which are normally going from one extreme to the other rather than just going down the one route and profiting from it. It’s probably the opposite with me, that I commit acts of commercial suicide by doing the opposite to what people would expect.

CL: Is there anybody who you feel is really injecting some originality into the [dubstep] scene right now or into the genre?

Dis Fig: To be honest, I don’t. I mean I still listen to a lot of dubstep now, but it’s all from the early 2000s. I know that there’s some good stuff going on in Bristol. There’s a guy, Bufi. I’ll definitely play his tunes out in the club. I haven’t, to be honest, really been keeping up with dubstep lately, but it does still hold a very important place in my heart.

The Bug: Yeah, I mean for me there’s definitely people involved in and around dub approaches of production and mindsets at the moment that I’m really inspired by. Lately, I think the thing that took my head off, and was probably my favorite album from last year, was Phelimuncasi, the South African gqom crew whose compilation of singles and recordings were put out by Nyege Nyege. But their use of rhythm, space, environment is amazing. And also Space Afrika in Manchester, I find their hybrid of ambient and dub techno really, really good.

My interests, like I said, are probably more outside of dubstep. I couldn’t even tell you very many current dubstep producers, but my interest in dub is still absolutely there. There’s no doubt about that. So for me, my interests are going to be more in the realm of sort of mutant dub producers and productions that surprise me, and they have that sort of “what the fuck” factor and “wow, I’ve never heard that before.” Whereas, if you’re asking in a way like what have you heard in a scene which has got a set formula, I’m not going to be as interested in that.

I think Equiknoxx‘s mutant dancehall is exceptional and incredible. I think Maral and Saint Abdullah in America are doing really interesting things with dub too, that’s dynamic, explosive, weird, and wonderful. When you want to follow a genre literally as a producer, because you just want it to exist in that genre, then I understand that’s appealing, but that’s just not where I’m going to be, really.

Dis Fig: I said before, I don’t feel like I’m able to speak on like the current dubstep scene because I don’t really know what’s going on. I can’t really list off names off the top of my head, but I definitely have been hearing like dub and dubstep influences coming from people who aren’t generally in that scene. I think for me, that stuff is a lot more interesting because it’s taking elements from dubstep or dub, but not trying to replicate the formula of it.

The Bug: I have to say that in this last year, because of corona insanity, I haven’t felt connected to club music really in any great way. The music I was listening to mostly was experimental, ambient, or hip-hop, where there was lyrical upfront dialogue as opposed to thinking about clubs. Because it was sort of depressing not being in a club, not dropping Bug rhythms or other people’s rhythms and not being able to test my sound system in Berlin or tour the world, checking for club music. Whether it be YouTube streams of DJs or whether it be looking at sites I would have looked at in previous years, somehow I just felt a bit alienated from it because I just felt distanced from the club and really immersed psychologically in my own mind state. And that’s probably also why I ended up recording six solo albums that are the opposite to club music, which are really monastic and and drone-based.

Dis Fig: Yeah. I can agree with you. I mean, I haven’t been listening to club music at all because I kind of feel like it’s irrelevant. I just mean irrelevant to what’s going on inside my mind and inside my soul at the moment.

The Bug: It’s not meant to be like “screw club music.” That’s not the point. The point is that we’re living in the craziest of times that I can ever remember in my lifetime, and it’s just like how your mind adapts to that. I mean, at the moment, I’m mixing a new Bug album for Ninja Tune which is absolutely in your face material, that’s absolutely about club. And even to get my own head around that at the moment has been strange—not because I don’t want to do it, it’s more to do with, “Wow, my head just hasn’t been there.” It hasn’t been my environment for over a year now, which is insane considering that’s all I’ve done for the last…god knows how many years.

Dis Fig: Yeah. I’ve just been straight up listening to guitar music.

CL: I’ve actually been listening to a lot of more like ambient dub stuff recently. I also love Space Afrika, but that’s about as dancey as it’s gotten for me because I’ve totally been in the same headspace.

Dis Fig: I think club music is just very physical too. It’s not just about being there and feeling the system, feeling the bass, but it’s also about being there with the community and feeling…

The Bug: Social.

Dis Fig: Yeah, exactly. We’re kind of in the opposite of that right now. So it’s hard to relate to that at the moment.

This element will show content from various video platforms.

If you load this Content, you accept cookies from external Media.

CL: Is there an ideal setting in which you would want In Blue to be heard?

The Bug: Yeah. It seems really strange having gone through the whole industry circus of “release, tour.” We’ve released, and when we’re not touring. We just haven’t had the chance to unleash it in a live environment. We knew Kode9, for instance, was very enthusiastic about hearing this album live because he knows the sort of sound that I crave and thinks, and knows, that that’s there. It’s just a case of the album being mixed as much with the idea of listening to it at home or on headphones and being immersed as much as possible—but being aware that when it came to the time that it could be played live, it’s going to sound super intense. Somewhere [physically] underground would be good. Somewhere with a really mighty sound system in a really small spot or alternately with a big tunnel, would be perfect I suppose.

Dis Fig: I mean, I’ve personally always felt that it was a headphone album, but the sonics definitely lend themselves to being on a rig too. We just haven’t heard it there yet.

CL: So you’re planning to tour it live once you’re able to?

The Bug: Yeah. Somewhere where you rock people’s bodies.

Dis Fig: Yeah.

The Bug: Oh, definitely.

Published February 25, 2021. Words by Chloé Lula.

Follow Electronic Beats