The X-ray Audio Project On Communism’s Blackmarket Bootlegs

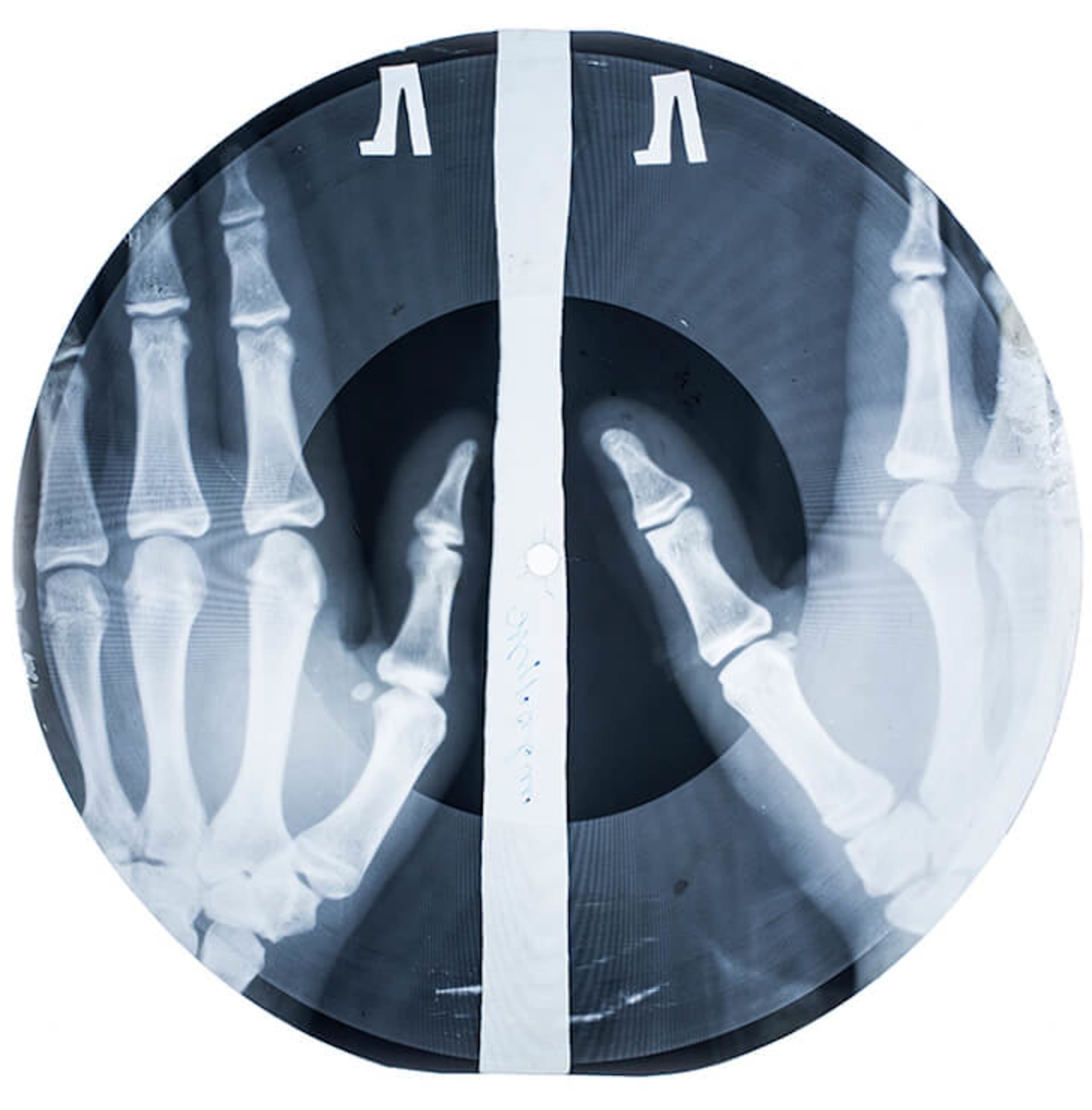

In the Soviet Union people used to hide their music in a number of creative ways. One popular way was to cut records on old X-rays sourced from hospital garbage.

These rare pressings are commonly referred to as Bones or Ribs. This year’s Krake Festival features a special presentation by Stephen Coates and Aleks Kolkowski who have unearthed a number of these unusual recordings. They will present their findings and even create their own from a performance by Alexander Hacke. We asked Stephen Coates a few questions before the Festival.

What is the X-Ray Audio project?

The X-Ray Audio project is a project to tell the story of the records—the bootleg records of forbidden music pressed to X-ray film made in the Soviet Union during the Cold War from about 1946-1964.

Why?

You’ve got a situation where you have a huge amount of culture that was forbidden. All culture was censored: art, film, even drama, literature. And of course music was censored too. By the time you got to 1946, there was a huge amount of music you were not allowed to listen to: Western music for sure, because it was Western, but also tango, foxtrot and certain rhythms. You also couldn’t listen to lots of Russian music that was made by people who were no longer considered patriotic. So if somebody became, let’s say if somebody fell from grace or was no longer considered acceptable, then all music that they made was forbidden.

So you had a situation where a huge amount of music was forbidden. And people loved this music and they wanted to hear it, so they were trying to find a way to hear it, and they were very ingenious we would say. In Leningrad they managed to bootleg technology so they could make new recordings of forbidden music. The way they were doing it was using recycled X-ray film that you can record on to make a vinyl record or grooves. This is a very strange part of the story. And it was easy at that time to get hold of X-rays because all the hospitals had to throw away their X-rays after one year because they were very flammable. Basically people discovered that you could make a record from an X-ray with a special machine. So that’s how it started.

What machine was this?

Well, interestingly, it was adapted from a German machine, the Telefunken. In English we call it a recording lathe. Telefunken made these machines in the late 1930s and ‘40s. They were usually used by journalists to make a recording of some news item to be sent to a radio station. Somebody found one of these machines. It’s interesting that we are in Berlin, because a Polish guy found—or stole, probably—one of these machines here at the end of World War II, and he took it to Leningrad. And this is how they started to make the records.

So you could say that it started from this one machine.

Yes, but if not from that one machine then from the principle of that machine.

So you can trace it back to this one machine, almost like a legend?

Yes, there’s a story about him coming to Leningrad with this machine and then they made machines like this to do it themselves.

What kind of records did they copy?

There were three types really. There was Western music: jazz and rock and roll, because they were forbidden. They were copying Russian music that had been very popular but was now forbidden. And they would also make their own recordings as well. Because, of course, in the Soviet Union you weren’t supposed to make your own recordings—it was illegal.

And these records that were made, were they mainly popular records?

Yes, they were all popular records. It was very much making the records that people wanted to listen to. For instance, “Rock Around the Clock” was super popular in the ‘50s. Why? I guess it had this energy for young people and it’s a song about dancing and “let’s just forget everything and dance”, that was very popular with young Soviet people. There were also some Russian popular songs too, like “The Cranes”, which is a rather romantic song actually. That was hugely popular in Russia.

How did these records get distributed?

They were sold on street corners. Obviously the people that were selling them needed to be quite careful, so they would sell them in dark corners, in parks, in special places where people would go because they knew they would be there. They had to be extremely careful because the police were looking for them, and also other criminals were looking for them. It was like selling soft drugs, so if you knew somebody who made these records, then maybe you would go to their apartment. They weren’t sold in shops or record stores.

Was there a curatorial role for the people who sold these records from their apartments?

Well we met a bootlegger recently, and he told us that he enjoyed introducing people to new music. He didn’t want to just sell them the stuff they knew already, he would try to say, “Listen to this song by Louis Armstrong, it’s really good.” So he enjoyed being a curator and bringing new music to people. At the beginning of this culture, the people who did it were music lovers and they were doing it because they wanted to share the music they loved. Later on it became a business, like a black market business. And then the people who were making records and selling them didn’t really care. It was just a money thing, you know? But there were always people doing it because they loved music. And it was a dangerous thing to do. One of the people we interviewed in St Petersburg spent two years in prison.

And what have been some of the weirdest records you’ve found? Or the most sensational?

I have never heard one, but there is this legend that there are recordings that start with some American jazz but that’s interrupted by a voice that says, “So you think you’re going to listen to some jazz, fucker?” People keep telling us that these records were made by the authorities or as a joke, but who knows?

What was the weirdest picture and music combination? Because I can imagine it can be quite strange.

Yeah, some of them are really quite beautiful. The obvious one is with a skull when the spindle hole looks like a bullet between the eyes. You know that when they were making that, they were doing this very carefully to get that effect. Some of them can look really beautiful—as they were fragile. These were not strong things, and they would start to deteriorate, to break down, and they can actually look amazing when they start to melt.

They were trying to get this hole in the middle of the skull shape? Do you notice a style that goes through these records? Can you trace certain pictures back to specific bootleggers? Like guys that use just skulls or other types of bones?

No unfortunately not. That would be very nice! I remember when I first started to look into it, I heard this story that if it was a jazz record, it would be on a chest etc. But no, because the important thing was the music. On many of those records you cannot see the image very well or they didn’t care so much about the image. They cared about the sound. The important thing was the music, and that was much more important than what it looked like.

And to preserve them, right? You mentioned that hospitals used to throw them out because they would burn?

Yes, they were very flammable. And yes, they didn’t last very long. So they would play them until they were destroyed and then just throw them away. It was disposable music. And because of that there are very little around today. People didn’t keep them because they were illegal. There aren’t really people who collect them. There are people who have them because they have a big collection of gramophone records, and there were maybe some of them in there. But as far as I know, nobody has really collected them. They are too difficult to find.

There is a book now, we published a book now with lots of examples of the record and this history of the bootleggers, with interviews etc. But also it’s a travelling exhibition, and the exhibition is very strangely going to Moscow, to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Gorki Park in 2017. You can also hear these X-ray recordings on our website as well.

Check out the book here and be sure to check out Stephen Coates and Aleks Kolkowski at the opening of Krake Festival at Urban Spree in Berlin here. Listen to some examples of these recordings here.

Published July 26, 2016.