Year in Review: Musicians Return to Their Visual Art Praxis in 2020

Music and visual art have always gone hand in hand, but in a year that put live music in limbo, the latter provided a lifeline for some producers and DJs.

Tom Scholefield always knew his life wouldn’t be spent in an office. The Scottish multimedia artist and Planet Mu-affiliate making music under the name Konx-om-Pax launched his career as a freelancer making music videos for labels like Warp and designing record sleeves for Hudson Mohawke and Oneohtrix Point Never during his time at the Glasgow School of Art as a way to sidestep the slog of a 9-to-5.

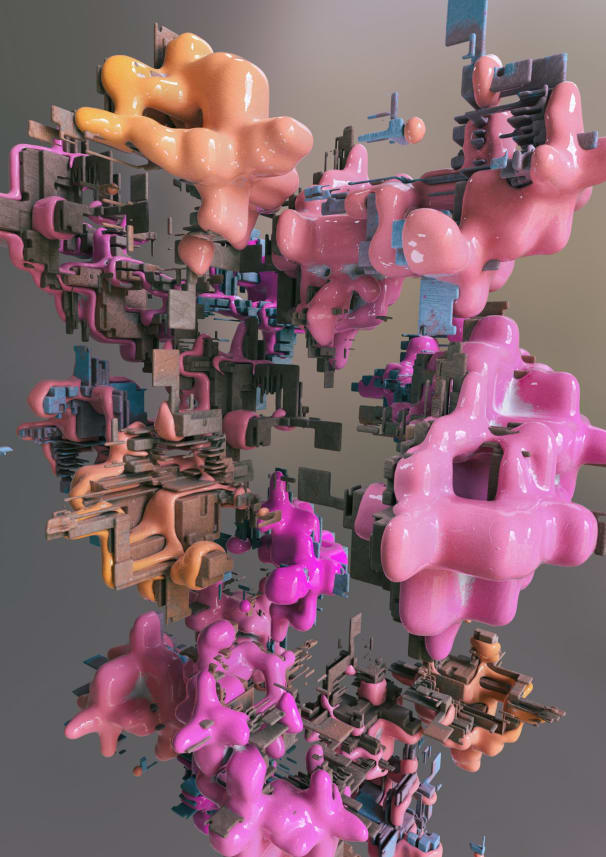

Throughout his oeuvre of music video designs, Scholefield creates alternative worlds that reinterpret the wild melodies and frantic rhythms of his cutting edge clients. “I’ve been making images for as long as I can remember,” he says. “I’d borrow my dad’s black and white apple computer in the early ‘90s when I was still in school to draw pictures with Macintosh’s Paint application.” As a designer, his work with Hyperdub introduced him to collaborators Kode9 and Mike Paradinas, who signed him Planet Mu, the label on which Scholefield has since released three albums and two EPs. His self-designed record sleeves contain striking shapes resembling sci-fi DNA helixes. Although Scholefield’s work as Konx-om-Pax has taken him across the world, performing his spaced-out, cinematic compositions and audiovisual shows at renowned festivals like Atonal, MIRA, and Sónar, graphic design remained his main source of income until two years ago, when he began touring with Kode9 and his own AV show. When the COVID-19 pandemic reached Europe, his fate, alongside all other live artists was thrown into limbo and he began immersing himself further into his design praxis. At the moment, he says he’s gone “back to focusing on more commercial ventures.”

Without a doubt, there is no way to tip-toe around the fact that this year has been absolutely financially devastating for musicians. To add insult to injury, the validity of working musicians’ careers came into question by politicians like British MP Rishi Sunak, who suggested that artists could retrain and “adapt” into new careers, a statement that was later heavily criticized by artists like Róisín Murphy and Sherelle on an interview with BBC Newsnight. “We’ve trained for so long to be in our jobs and we’re completely suffering,” the London-based DJ stated bleakly in a quote that resonated across the music community.

DJs and producers working in other fields than music is of course nothing new, and there are countless examples of DJs and producers who have a background in other forms of art. To name only a few, Lena Willikens, alongside a handful of Salon des Amateurs affiliates including co-founder Tolouse Low Trax, who attended the Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf, visionary DJ Juliana Huxtable, who has been making groundbreaking multimedia art for the past decade, French multimedia artist Zoë Mc Pherson, who released her States of Fugue LP with a sleeve designed by Szilvia Bolla and Jonathan Castro for her SFX label alongside a handful of audiovisual perfomances, and PAN-affiliate Elysia Crampton, whose’s LP ORCORARA 2010 (one of our stand-out records of the year,) was originally commissioned for the Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement in Geneva, are all among those who can rightly stake their claim across several transdisciplinary mediums.

But in a year that has thrown the very notion of most musician’s financial security into question, the COVID-19 crisis has seen many (at least temporarily) return to the professions they originally trained in, as has been the case for Berlin-based artist Rhyw. Part of the techno duo Cassegrain, he co-runs the Fever AM label with Mor Elian and has been doing the label’s designs since it launched in 2017.

Rhyw, who studied graphic design and illustration at the London College of Communication and worked full-time as a designer after graduation, quit this career path when his music career took off in Berlin with Cassegrain half a decade ago. “I continued doing small, mostly music-related projects here and there, such as the cover artworks and event posters, but no real time-consuming projects until this year happened,” he says. Aside from taking on commercial projects outside of his artistic scope, 2020 has been a productive year for Rhyw, who released two EPs including the polyrhythmic hip-shaker Sing Sin for German techno institution Seilscheibenpfeiler. On the music video for his latest single “It Was All Happening,” off his Loom High EP, he tapped musical acquaintances and friends like Ben UFO, Shanti Celeste, Parris, Pariah, Peder Mannerfelt, and Mor Elian, to pose as 3D figureheads floating together in space. “I thought it would be funny to bring everyone together [in the absence of real-life gatherings] and have everyone up close rubbing, rotating and merging faces,” he said of the video, which premiered on FACT’s YouTube channel in July.

This element will show content from various video platforms.

If you load this Content, you accept cookies from external Media.

For Dutch DJ and collage artist Fenna Schilling AKA Fenna Fiction, working with analog materials was initially a method for improving her mental health while balancing her Bachelor thesis five years ago. “It was something I did as a teenager, but at that point [I had neglected the praxis] for about ten years,” she says, looking back on a hobby that has since turned into a flourishing career. One of her earliest pieces of work was the record sleeve of techno producer Parris Smith’s Virgin of the World EP, but her liquid machinations and abstract collections of shapes have more recently graced the album covers of Phillip Jondo’s Garland project as well as mystical Dutch synth-pop enigma Meetsysteem and his second album Cr:GO for Nous’klaer Audio. Her work is so abstract that the original source material is hard to discern, however, she reveals that her inspiration mostly comes from vintage photographs and illustrations found in old books. “I especially like product photography or retro advertising where you can see the traces of film or the camera in the end result. The limits of older printing technology created a lot of warmth, which is something I always try to bring forward in my work.” As a DJ who is part of the Dutch music scene, Schilling says it feels more natural to imagine art for music than making art for a gallery. “I never create art for art’s sake,” she says, preferring her work to serve a specific purpose instead. “Enjoyment of beauty is something worthy in itself. My pieces don’t need much explanation or theoretical context.” In this aspect, her art resembles the music they are meant to represent visually.

Although DJing wasn’t Schilling’s full-time job before the COVID-19 crisis hit Amsterdam, she says she still mourns the loss of that part of her life, and her work as a DJ for the time being remains on hold. “I haven’t found any inspiration to do live streams and currently it’s even hard to listen to music. I feel very lucky that I make visual art too, and that I can do it from home.” Schilling says her visual practice used to come solely from the music industry, like creating posters for party’s and festivals, flyers, and record covers.

At the moment, Schilling feels relieved that her art practice has expanded beyond the musical realm for the past year. For her, it’s been freeing to know that she’ll always be a part of her local music scene but not depend on the industry in terms of her financial autonomy. She hopes that “2021 will be a year where creativity can meet in real life again because that’s what I’ve been missing the most—meeting people in spaces where you share a moment of joy and inspiration.”

Caroline Whiteley is an editor at Electronic Beats based in Berlin.

All images by Konx-om-Pax, Rhyw, Fenna Fiction, and additional graphic design by Ekaterina Kachavina.

Published December 16, 2020. Words by Caroline Whiteley.

Follow @electronicbeats