An Oral History Of Berlin Dub And Bass Party Wax Treatment

Although Berlin’s world famous record store Hard Wax is best known for playing an integral role in the development of dub techno and its meticulously curated stock of dance music, the shop’s DNA has always included classic dub, dancehall and reggae. Owner Mark Ernestus was an avid digger of Jamaican 7″s and all things dub before he opened the shop in the fall of 1989. In the latter half of the ’90s, a chance encounter with a Japanese dancehall enthusiast and club owner set a process in motion that eventually resulted in one of Berlin’s most cherished parties: Wax Treatment. Since its inception in 2009, it has become a refuge for lovers of dubstep, bass music and dub and reggae alike. One of the key ingredients to its beloved vibe and reputation is a heavy-duty Jamaican-style sound system, the Killasan, which was shipped from Japan to Berlin in the early 2000s. In this oral history, some of the main forces behind Wax Treatment tell the story of the party and its sound system.

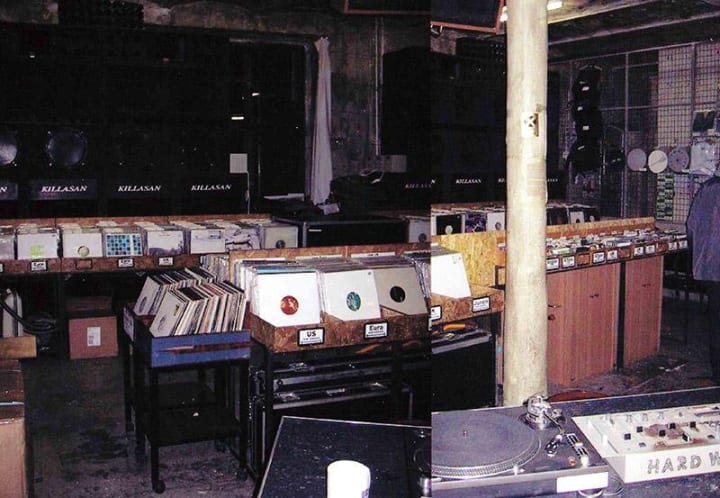

Fiedel [Berghain and Wax Treatment resident, sound engineer and producer]: Wax Treatment really is the story of a sound system: the Killasan.

DJ Pete [Hard Wax employee and Wax Treatment resident who produces as Substance]: The tale of how the sound system came to Berlin is extremely long and complicated. I’ve got some gaps in my memory as well. Originally, it definitely belonged to Naoji Kihira in Japan.

Mark Ernestus [Hard Wax owner and one-half of projects like Basic Channel and Maurizio]: The short version is that Naoji (AKA K-Boss) was running dancehall and reggae parties, and then later opened his own clubs in the Osaka area. At some point in the early ‘90s—based on years of planning and research in Jamaica—he had this Jamaican-style sound system built in Florida. The original system was twice the size of what we have in Berlin, plus additional components that had been built in Japan prior to that.

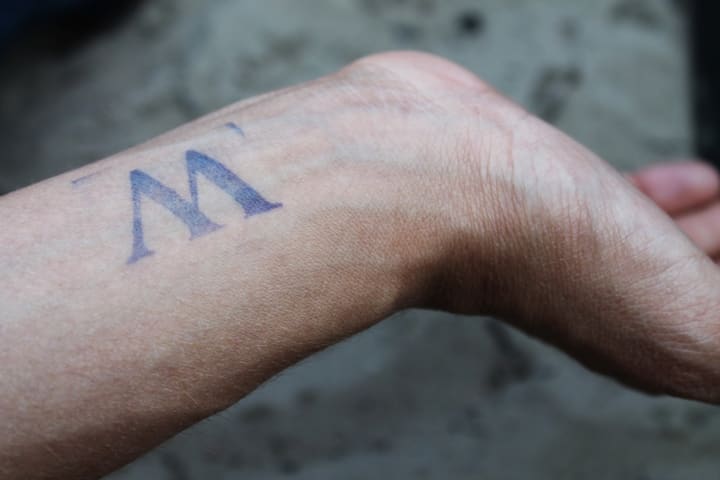

As I understand it, Naoji had become quite tired of the dancehall business and was interested in electronic club music when he visited Berlin in 1996 with his wife, Naoko, and Killasan crew members Soldier and Dai. I met him at Hard Wax, and we got to talking. Contrary to him, I had gotten a bit tired with the way techno was going and my old interest in reggae was regaining ground, so it was a funny meeting of minds.

Anyway, I visited him in Osaka shortly afterwards. We kept in contact whenever I was in Japan and sometimes played records together. In 1999, his big club Jugglin Link City was destined to close down and he was considering doing something in Berlin. Then in 2001, we had a night planned with [the Berlin-based drum and bass crew] hard:edged at WMF where Lloyd Barnes (AKA Bullwackie) was supposed to appear on the mic. In the end he couldn’t make the flight due to some last-minute difficulties in New York, but Naoji went ahead and just shipped the system to Berlin to put it in my hands for the time being.

Fiedel: That must have been in the spring or summer of 2001. Suddenly the sound system was standing there at Hard Wax.

Mark Ernestus: I asked Fiedel if he would be willing to look after it in Berlin as technician or manager in general. So Naoji came to Berlin with the original technician, Mr. Kida, who gave Fiedel a proper technical introduction. They worked on it for about three days to get it running.

Fiedel: I had to get some transformers specially, otherwise the system wouldn’t have run. In Japan, everything runs on 110 volts—not 220 volts like in Germany.

DJ Pete: Mark and Naoji wanted to get the Killasan on the road. Mark and Fiedel came up with a package and then announced that it could be rented, engineer and all.

Fiedel: Ever since then I’ve been responsible for organizing the events—for the transport, the setup and being onsite as an engineer. I also take care of the maintenance of the system.

DJ Pete: Fiedel had a small team, and they went off together. [All the bookings] were for reggae gigs.

Fiedel: Naoji’s idea for the rental fee was based on Japanese prices. I told him right away that it was way too much and that you could maybe get half of that in Germany. In Berlin no one has any money anyway, and in Germany there aren’t all that many promoters who even need a system like that.

DJ Pete: There isn’t really anything like a sound system culture over here, so the Killasan didn’t see that much action. It was used at a couple of student parties in Greifswald, where they had a reggae floor, a few special events in Berlin and also at the release party for the Burial mix of “See Mi Yah” on Rhythm & Sound.

Pinch [UK dubstep pioneer and Tectonic label head]: I saw the system stacked up in the shop for a number of years. One time I mentioned to Torsten [Pröfrock, AKA T++, who works at Hard Wax] that it seemed to be a bit of a waste and asked if he’d any plans to get it out and set it up. It wasn’t long after that I heard about a night at a club called Horst Krzbrg—Wax Treatment. I got to play and experience the system myself shortly after.

Mark Ernestus: That was at the beginning of 2009. [Tresor club founder] Johnnie Stieler, who I knew from the early Tresor days, wrote to me after I had lost contact with him around ‘93 or so. He said that he was going to open a club at this very nice location and he wanted me or us [Hard Wax and affiliated DJs] to do a regular night there.

Johnnie Stieler [Tresor and Horst Krzbrg club founder]: Mark and I hadn’t seen each other for years. In the early days of Tresor we’d done a lot together and had a blast, especially on tours through Europe with Underground Resistance. He was the driver and I was the tour manager.

Mark Ernestus: Until Johnnie’s call I wasn’t keen on being responsible for a regular night. I hadn’t been actively looking for a venue to run the Killasan system on a regular basis, but I was keeping an eye out for a suitable setting that wouldn’t give me too much of a headache.

Johnnie Stieler: By the end of the ‘90s I was basically out of the whole club scene. But I always knew that if I ever opened a club, Mark would be the first person I’d approach.

Mark Ernestus: I said I was interested if we could do it on the Killasan, which he was happy to agree to. I had a list of criteria in my head [in order] for the setting to make sense, and when we looked at Horst Krzbrg and discussed the possibilities, everything was as close to ideal as one could reasonably hope for.

Johnnie Stieler: I didn’t even know about the Killasan system at that point in time. I’d always seen it standing around at Hard Wax and wondered why they used those speakers as decoration.

DJ Pete: Then it all went super fast. When we visited the space, Johnnie and his team were still in the middle of the construction work. Of course, the fact that we knew him so well from the Tresor days was also important.

Johnnie Stieler: One of my best friends, who played dub, died shortly before we found the location. He was the one who had opened my ears to classic dub and digi-dub in the first place. So when Mark came along with his idea, for me it was like divine intervention. It all made perfect sense right away. I didn’t ever want to do a techno place again. I don’t like to repeat myself and I get bored easily—with music as much as anything else. Dub was still somewhat of an unknown quantity for me, and it was a pretty good fit, biographically speaking; I listened to David Rodigan’s show religiously in the GDR days, and my favorite part was always whenever he played dub. To me, it was the most amazing thing ever. A friend and I did a couple of our own dub experiments back then. His father was a musician and had connections, so we had a Roland tape echo. We experimented with that and with cassettes. It didn’t ever really amount to anything and it was also pretty short-lived, but it did influence me. When Mark told me the complete history of the Killasan sound system—that was the icing on the cake.

DJ Pete: Horst Krzbrg was perfect, even just because of the location. It was central—in Kreuzberg—and easy to reach with the U-Bahn. The size of the club was ideal for the sound system as well.

Johnnie Stieler: Then Fiedel came along and measured the place and found out that the system covered exactly one wall. That was sensational.

Fiedel: There was even enough space to store it right there on site.

Johnnie Stieler: Every time the Killasan was brought from the basement and set up, it was like a kind of ceremony. There were always a bunch of volunteers who hauled all those speakers up the stairs. It always felt extremely reverent.

DJ Pete: The best part was that only the speakers had to be moved because the cables and amps could be stored while they were practically still connected. The name for the party presented itself quickly: Wax Treatment.

Fiedel: The only musical premise we had was: there had to be bass.

DJ Pete: Of course, dubstep was a big thing when we first started, as was bass music in general. At that point, its was perfect to have a place like Horst, where you could really celebrate the music. Of course, reggae and dub were also very important and also what we at Hard Wax call “outernational” music—Burnt Friedmann, Honest Jon’s releases and stuff like that.

Mark Ernestus: The idea was as simple as it gets: sharing great music on a great sound system with an appreciative audience in an atmosphere of general niceness where competitive billing, promotion and business didn’t matter.

DJ Pete: Word spread pretty much all by mouth. The core DJs were from the Hard Wax camp, of course. We never really did any proper booking. We mostly just invited people who happened to be in town anyway. We hosted Pinch, Mala, Theo Parrish, Loefah, Shackleton and sometimes Ben UFO. It was our dream not to announce any lineups or play times at all.

Shackleton [UK producer known for blending dubstep with eclectic influences]: I had moved to Berlin in 2008 and got to know Mark through my music. I was right in time for the beginning of Wax Treatment.

Pinch: I had met Mark Ernestus through Sam Shackleton. Having been an enormous Basic Channel and Rhythm & Sound fan, it was a real honor to play there. It must’ve been around when Sam [Shackleton] and I were writing our album for Honest Jon’s that I was booked there for the first time. I was going back and forth between Bristol and Berlin quite a bit, and it made sense to play Wax Treatment on a Sunday, hang out a bit and then hit the studio with Sam.

Fiedel: The fact that it all ran through Mark and Hard Wax put us in the luxurious position of not having to persuade anyone to play with us even though we could only offer a small fee.

Johnnie Stieler: The first Wax Treatment was a revelation. Then and there, it became clear that it had been a good decision to open a club again. The whole atmosphere totally worked.

DJ Pete: The very first event was amazing. Of course, everybody was nervous about who’d show up and how the music would sound on the system. I wasn’t there for the soundcheck. It was also a reunion of sorts, because I hadn’t seen Mark or heard him play for ages. It was the same for him, and after the party we were both totally inspired by the other’s set.

Fiedel: At that time there was a lot of new stuff coming from the UK. Of course, it was perfect for our sound system. When Pete played a dubstep set, it really came alive and created this warm bass.

DJ Pete: I was really deep into the whole dubstep thing back then, and I was surprised that Mark also played dubstep. I talked to him and it turned out that all the records he’d played came from Jamaica, from a couple of Jamaican producers who were obviously influenced by UK dubstep. It was a real epiphany for me. It’s always really cool to observe how the individual styles affect each other across the continents.

Shackleton: Wax Treatment was very different from your standard club night on some levels, and on other levels it was exactly the same. Differences being: you tended to get a very dedicated crowd, but it was a minority. I’d say it was a little bit like with the early dubstep days, when people have this image in their head like, “Oh, it must have been legendary at FWD>> [a famous pioneering dubstep party]!” Well, actually no, it was more that it was a minority taste.

Pinch: It was a very switched-on audience that knew a lot about the music. It’s always fun to play in situations like that. It also pushes you as a DJ. You start to dig a little bit deeper in your record collection.

Shackleton: When I say [the music at Wax Treatment] was a minority taste, I mean that it didn’t really go off right away, numbers-wise. It was mostly on Sunday evenings as well. Even in Berlin people wind down on a Sunday evening…sometimes. But when it was on a Friday and they had a big-name guest on the lineup it would be absolutely jammed. In that sense, Wax Treatment was very often like a standard club night.

Fiedel: The whole thing was aimed more at music lovers.

Paul St. Hilaire [AKA Tikiman, a singer, producer and False Tuned label owner]: I loved it! It became like a second home very fast. Even when I wasn’t specifically booked I would sometimes go on the mic—like when DJ Pete was on. If they booked someone from the US or the UK, though, I very often didn’t feel like doing that because they had their own thing going on.

Shackleton: As a big fan of all the Rhythm & Sound records and the whole connection with Hard Wax and its staff, Wax Treatment had a special reputation from day one. Having Tikiman on MC duties is a big honor for a lot of people, myself included. I was like, “Wow, Tikiman is toasting over my stuff!”

Paul St. Hilaire: I really enjoyed checking out all the other artists. I can honestly say I enjoyed all the sessions. The main thing is to appreciate the music, the sound and the people. A lot of people, I think, saw things the same way, and that’s what made Wax Treatment special.

Fiedel: In the beginning we held the parties on a monthly basis. The parties during the Carnival of Cultures were definitely a highlight. The sound system was set up outside in the courtyard.

Johnnie Stieler: The Carnival of Cultures went right past us in May every year and always stole a great deal of the crowd from us during that weekend. One day I was standing in the courtyard of the building where Horst Krzbrg was located and I had a vision. If you were to do an open-air floor there, then you could possibly turn the tables. So I got myself a permit from the property management, and when the day arrived, we occupied the part of the courtyard that belonged to the post office next door. There was a ramp where post trucks would unload their stuff during the week, and we turned that into the stage.

Pinch: That year was actually one of the first times I played Wax Treatment, [and I played] with Peverelist. Outside on the streets the carnival was going off, and we were playing in the yard. It was amazing.

Johnnie Stieler: The very first party where we also opened the courtyard was sensational. That’s also where the sound system’s potential finally became clear. In the club, you didn’t notice the impact of the bass so well because the place was really pretty small and the bass waves didn’t have enough space. In the courtyard it was an entirely different story. Out on the street, your hat would almost get blown away. We didn’t take an entry fee because it was just too difficult while the Carnival was raging outside. But we did our best to get our guests extremely full of drinks, so at least we’d earn a bit of money from the whole thing.

DJ Pete: I always found the Carnival of Cultures to be a bit difficult, because there were a lot of passers-by who weren’t into the music. But presenting the Killasan outside was great, of course. That’s the whole idea of a sound system. It’s supposed to be outdoors in a backyard or on the street.

Fiedel: For the second Carnival of Cultures it was so crowded that we had the feeling we’d need a doorman and charge for admission after all.

Shackleton: In terms of operating the sound system I realized that there was a big difference between England, where it seems to be very much about piling on as much pressure as possible, versus with the Killasan. Mark and Fiedel were meticulous, rather than really pushing it toward something like [the UK model]. You always had the feeling that it could go a lot more.

Pinch: I guess that was my only complaint: that they never turned it all the way up. You have this enormous stack of speakers but it’s never really at full volume. Mark is always aiming for audio perfection rather than a show of power. And it’s not just about volume; it’s about frequencies, too. Fiedel and Mark take out a lot of the upper midrange with their EQ to give the system a certain sound.

Fiedel: There will always be people who want it louder, but the system is not designed to exert pressure in the chest or the gut. It surrounds you with sound and envelops you; it’s not punchy. You feel it, but it’s softer. This is why people sometimes get the impression that it’s not loud enough.

Pinch: I grew up around UK sound system culture, which was very much driven by sound clashes, where one of the main aims is trying to outdo the other system. One of the easiest ways to achieve that is with volume and power in the low end.

Fiedel: In my opinion, if you need to put earplugs in, then something isn’t right. You’re supposed to feel the music, it’s supposed be loud and, most of all, sound great. After all, you wanna to hear it. So why wear earplugs? As a DJ I always try to work that way, especially at the Berghain, where I’m somewhat familiar with the system. It simply shouldn’t be so loud that it starts to hurt.

Paul St. Hilaire: When I perform I really need to hear myself in a certain way: not too loud, not too aggressive, not too anything. That’s another reason why I love to play at Wax Treatment. Mark and Fiedel just know their sound system and exactly how it should sound.

Johnnie Stieler: Our neighbor was the post office; we were only separated by a thin brick wall. During Wax Treatments, the Killasan sound system always blew the letters out of the sorting machine. They didn’t take that very well.

Pinch: Wax Treatment’s use of the Killasan is definitely culturally different from traditional sound system set-ups over in the UK. But having said that, I believe it was King Tubby whose sound system was supposed to be one of the best but wasn’t the loudest. It wasn’t dominant, but meticulously maintained. I think Mark takes more of the audiophile philosophy rather than trying to throw his weight around.

Johnnie Stieler: One of my personal highlights took place after a Wax Treatment party. Fiedel generally adjusts the PA to be rather gentle on the ears, and during the party it was positively quiet the whole night. I think we even discovered later that the limiter was broken. After Fiedel and all the guests had left, we went on listening to music. Suddenly it was super loud and we were just like, “Ahhh, finally!” Then Mark played a special version of [Black Roots Players’] “Slow Tempo”. I knew that one from the David Rodigan Show in the ‘90s. This riddim has really haunted me for 20 years. I can’t exactly say why, but the first time I heard it on the radio was life-changing. When Mark played it on vinyl I totally freaked out. I couldn’t believe it because I had searched in vain for years for “Slow Tempo” and I hadn’t even heard it anywhere. Then I tried to get him to give me the record or at least send me a file of the track. He still hasn’t done it to this day. By now I’ve given up asking.

DJ Pete: One thing that surprised me in the beginning was that the Berlin reggae scene was never really interested in Wax Treatment. There was hardly any overlap. In retrospect, I think it’s a good thing. Hard Wax stands for electronic music, even though we stock reggae. Also, the reggae scene in Berlin stopped evolving at some point. Those three or four big DJs are still playing, but, as far as I can tell, there’s no movement happening. Wax Treatment went in a different direction musically. Mark was one of the first—if not the first—people to show that dancehall and reggae can be very experimental and also electronic. Whenever Mark plays, he attracts guests who’d most likely wind up exclusively in the reggae scene.

Paul St. Hilaire: You know, the reggae crowd—they’re conservative. I play music and I’m very open in my mind about music, but certain fans stick to what they know, musically, but also in terms of venues they go to. So if Wax Treatment was taking place at YAAM [Young African Art Market, a concert venue and multicultural space in Berlin], for instance, I think more reggae fans would show up because, indeed, Wax Treatment is also about real reggae.

Johnnie Stieler: Our final year [at Horst Krzbrg], 2012, was weird in some ways. Suddenly bass music wasn’t that popular anymore, even though there was an incredible amount of good music. But our audience wasn’t interested. Wax Treatment got stuck in that.

Fiedel: At some point it became difficult to keep the bookings varied. We didn’t want them to become arbitrary, so we switched from holding parties monthly to every three months.

Johnnie Stieler: If you had a party today with Shed, DJ Pete, Shackleton and Mark Ernestus, plus Tikiman as MC, the crowds would flock to you. Wax Treatment’s lineups always looked like that. But the place just didn’t fill up anymore in 2012. Sometimes things just wear out. Once the world has moved on, it’s over fast. You have to come to terms with that.

DJ Pete: The whole thing ran out of steam somewhat [at Horst Krzbrg].

Johnnie Stieler: Then, suddenly, our lease was terminated. The end of the club was extremely abrupt.

Mark Ernestus: It was like, 2:30 in the afternoon, and I was having lunch with some guys from Hard Wax. Then Johnnie called and said: “Long story short: the landlord is kicking us out. We have to get everything out by midnight.”

Fiedel: Mark called me and told me the sound system had to be out of there by the next morning. Horst Krzbrg was closing. So I got a truck and called people to help and there we went.

Johnnie Stieler: We had 24 hours to get everything out. Everything.

Fiedel: When we were done, it was the middle of the night. We didn’t know where to take the sound system and had to just leave it in the truck overnight, out there on the street. The next day, Mark called. He’d spoken with Dimitri Hegemann from Tresor, where there was a wall available for us. So we went over to Tresor, unloaded the truck and stacked the Killasan there.

DJ Pete: From one day to the next, the club was shut down. It was shocking. Even Shackleton, who had his studio in the club, had to leave overnight.

Shackleton: That was very sad. I was very grateful to Mark then, because I didn’t have a car and I had to get all my stuff out as well. We had such short notice because they only gave Johnnie 24 hours to clear everything out. I’d been out the night before; it was a weeknight, but for some reason I’d been really drunk and I think I’d been to a football game. The next day was one of those rare times when I decided I wasn’t going to answer my phone. It kept ringing and ringing and I’m thinking, “Stop bloody ringing me!” Finally, I looked at my phone. I had maybe six missed calls from Johnnie, and it was around 4:00 in the afternoon. Everybody who’d ever been associated with Horst was there trying to get everything out. There must have been about 30 people there altogether. That was pretty miserable, I have to say.

Fiedel: After we’d processed the shock, it ultimately didn’t take that long until Mark had a new venue: Kiekebusch. It was an open-air location with a lake, a sandy beach and a forest around it.

DJ Pete: Fortunately, the connection to the new location in Kiekebusch came very quickly. We could also store the sound system in a container there.

Mark Ernestus: Alex Pehlemann, who had organized a few events with the Killasan in Greifswald and Poland, had been telling me for a year or more that his friend Bert Greif has this amazing location that would be ideal for an open-air Wax Treatment. At first I wasn’t really interested because we were happy at Horst and it’s always a big effort to move the Killasan. Then at some point I went to take a look anyway and thought what an idiot I’d been not to check it out sooner. That was around the same time Horst closed down.

DJ Pete: With Kiekebusch, Wax Treatment and the sound system have found something like a final destination.

Fiedel: If it weren’t for the unpredictable German summer. If the weather forecast is bad, then a lot of people don’t even bother to head out and hope the weather will be good anyway. It’s quite a distance from downtown Berlin. We’ve had that painful experience a couple of times. Organizing parties there takes quite a bit of effort, because the entire infrastructure has to be dragged out there and set up: gastro, toilets, electricity—everything.

DJ Pete: Honestly, I always find it most gratifying when I can hear the sound system in a club. When it’s open-air you look for good spot, of course, but the Killasan’s got more power when it’s in a club.

Fiedel: I prefer to hear the sound system outside, where it’s got space to unfold. That’s exactly what it’s made for.

Shackleton: I love when you’re walled in by sound and there’s no escape from it apart from being on the dance floor or getting out of the room. You can’t beat that intensity. Even if I’m getting on to be an old bastard now, it’s something that you always love. And there’s another thing that is always special about Wax Treatment, no matter if it’s held indoors or outdoors, which is that the dancers don’t face the stage.

Fiedel: Wax Treatment is the only event where you basically just see the backs of the dancers because they’re all dancing with their faces towards the sound system. No one looks at the DJ.

DJ Pete: That’s always a highlight, visually. The guests don’t look at the DJ, but at the tower of speakers instead. The Killasan is the focus of attention. That was truly special, and it’s still like that. When talking about Wax Treatment, that’s one of the most unique characteristics. No one’s looking at the DJ. Perfect!

Published January 13, 2016.