Minimalist Pioneer Tony Conrad Talks To Krautrock Band Faust

Few have achieved as much in both the music and fine art worlds as Tony Conrad. In the ’60s, Conrad helped pioneer minimalist drone techniques together with the likes of La Monte Young, John Cale and Terry Riley (among others) as The Dream Syndicate before developing his trademark strobing “flicker” film method that became central to experimental cinema. At the time, Conrad characterized the New York downtown music scene as a search for “something just beyond music, a violent feeling of soaring unstoppably, powered by immense angular machinery.”

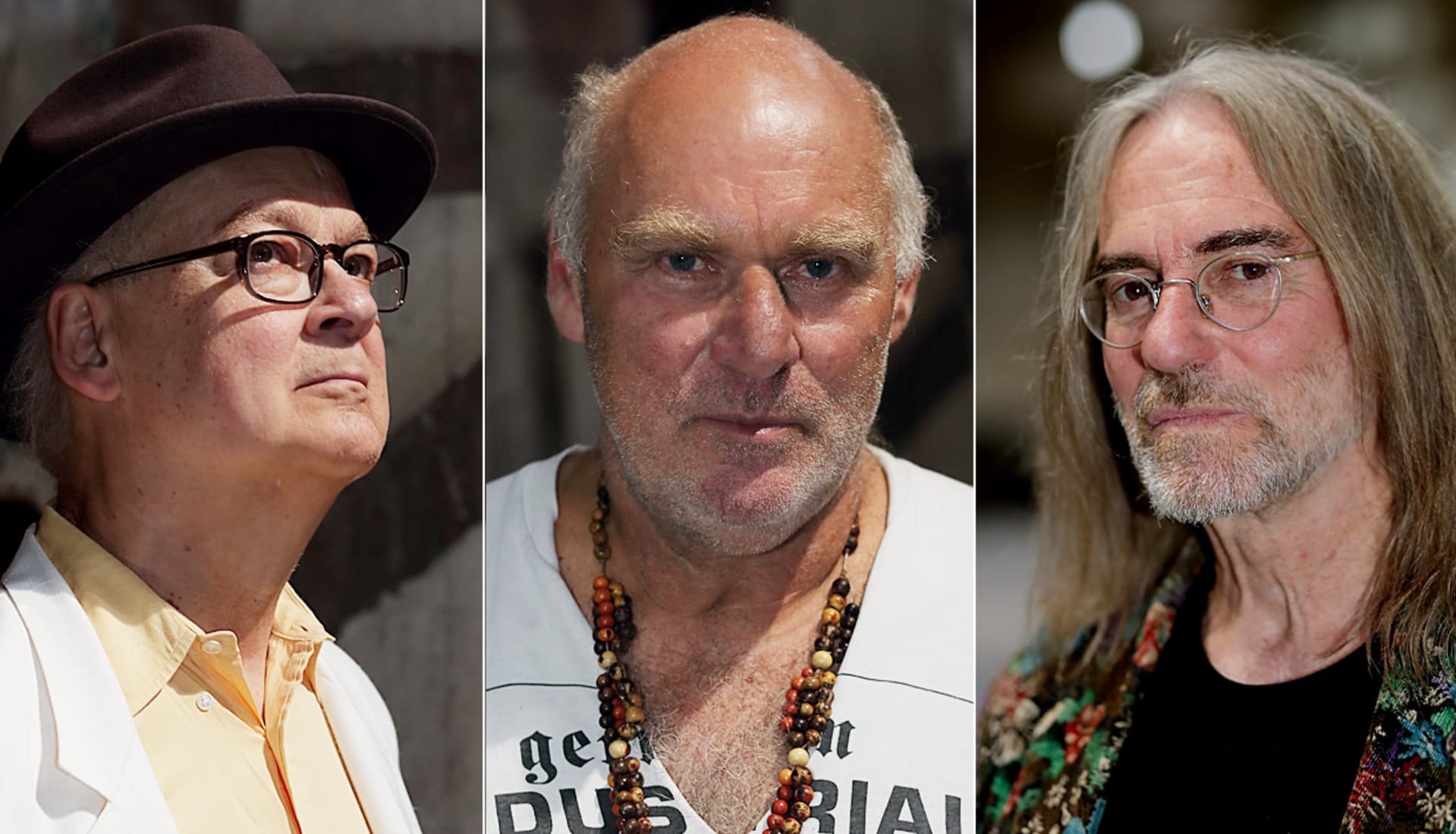

It was also a fitting description of the artistic kinship he would strike up with the German band Faust. Known today as one of the most important krautrock bands of the ’70s, Faust merged jazz and rock techniques with radically improvised fluxus and avant-garde interventions, using tape, metal or whatever else was at hand to create authentically new music. Conrad approached the group to collaborate, resulting in their 1973 minimalist masterpiece, Outside The Dream Syndicate, which they recently performed at this year’s Berlin Atonal Festival. Daniel Gottlieb sat down with Conrad and Faust’s Jean-Hervé Péron and Werner “Zappi” Diermaier to moderate a conversation on their collaborative history.

Tony Conrad: Today, the 22nd of August 2015, is the day that Faust and I come together for the ten-thousandth time. Well, really it’s the third time—somewhere between the third and ten-thousandth time.

Jean-Hervé Péron: For me, it’s our second time together, and for Zappi it’s the third. In my mind we’ve played two shows together in the past. But Zappi mentions you played together as a duo in New York.

TC: You weren’t there in New York?

JHP: That’s right.

TC: What were you doing?

JHP: Gardening. It’s the thing to do. I take care of all the weeds and the dirty, nasty jobs, whereas my wife takes care of the real gardening. So I’m an unskilled gardener, and I love it. I’ve a passion for physical work. Mind you, Jean-Jacques Rousseau said that the problem with mankind is that it can’t deal properly with its garden.

TC: And Confucius said…what did Confucius say? I forget. So this’ll be the third time that we’re playing together? I first heard your music because [film critic and record producer] Uwe Nettelbeck sent me your records along with stuff by some other bands. I played the records and thought, “It’s like rock ‘n’ roll, but this is far-out stuff…and this is from 1971?” In New York, we knew about psychedelic music and bands like Amon Düül, but Faust were doing stuff that was weird, and I thought, “This sounds nice. I should go and talk to them.” Did you guys know Amon Düül?

JHP: When we were living in our self-designed studio in Wümme, we voluntarily secluded ourselves from the outside world. This was a choice that we made. So, while we were aware that there was a scene outside Wümme, we didn’t know anybody. No Can, no Kraftwerk, no Cluster—no nobody.

Zappi Diermaier: We lived in Wümme like it was a cloister.

TC: For a long time?

JHP: There are two ways to approach time: the way you feel it and how it passes in reality. For me, I felt like Faust’s days at Wümme lasted two years.

ZD: I think it was three years all together.

TC: But you guys must’ve been, like, 15 years old back then. You look like you’re only 50 these days.

JHP: That’s kind of you, Tony. Actually, I was 19 when we moved to Wümme.

ZD: And I was 20.

TC: 20—now that’s an important age. I loved being 20. When I was 20, I was beginning to make this drone music. When I heard of you guys, which must’ve been about 10 years later, I was thinking, “Oh boy, I better record Outside The Dream Syndicate before I forget how to play it.” So that’s why I wanted to go see you at Wümme. That place was like an ant colony. There were chambers in different parts of this big building. There was a guy in the attic writing operas, everyone’s smoking a lot of weed and the dog outside is biting everybody. Nobody bothered to leave the house because you’d go outside, look all directions and there wouldn’t be another house for as far as the eye could see. Once a week or so, Uwe would come in his car with some groceries. It was like living in an oasis.

JHP: We shared girlfriends, we shared dogs and we smoked a lot of mind-expanding substances. Luckily, we had the great opportunity to be introduced to your world and concept of music. But you’ve got a very important point here, Tony, in mentioning that the drone “scene” existed 10 years before Faust was actually making music.

TC: In my mind, it wasn’t a scene. In a way I was like you: isolated and out of contact with everybody. There was nothing. I mean, I was listening to rock ‘n’ roll and Peggy March—stuff that had nothing to do with drone music. Also, the avant-garde music of the day was focused on very different things. So for us, it was like, “Whoa, this drone music we’re making is the best shit in the world.” That’s what we thought at the time, but you can’t do the best stuff of anything, ever. After all, the idea of using a single note as a basis for composition has existed in music all over the world for thousands of years. In that respect, La Monte Young’s idea of an eternal music—although completely false and wrong and misguided—has some kind of sense to it. Drone functioned in Western culture in a way that broke down the barrier between high and low music culture. The next thing to happen in our little circle was The Velvet Underground and the old connection with Andy Warhol furthered this breakdown of high and low culture. With Faust, the feeling was similar. You were making rock music that was devoid of commercial sensibility. Like you say, Jean-Hervé, we didn’t care what anyone else was doing.

JHP: What happened to us? What made us go in that direction?

TC: To you?

JHP: To us in general. Did our parents mistreat us? Were we stepped on when we were born?

TC: We were reared on the avant-garde spirit of happenings and fluxus and the breaking down of boundaries within high art forms. It was obviously theater, but it was also music. La Monte Young was writing pieces where he would feed a piano some hay and things like that. But these avant-garde gestures can happen any time; they’re not just reserved for 1960. It was happening in 1970 with Faust, and maybe it will happen in 2015. I don’t know who’s doing it now, though. Except for me!

JHP: I think it’s important to reiterate, as you mentioned, that drone and all these ur-musics—these primal ways of expressing oneself—have existed since before we were born. It’s the stomping of the Britons, the overtone singing of the Aborigines and the Inuit.

TC: The Celtic music of Europe is a particularly interesting case. It’s unknown because it was never recorded, yet throughout Europe you see evidence of bagpipe-esque instruments in Hungary, Germany and France. The Celtic origins of the tradition must have been somehow stamped out. I wish we knew more about this.

JHP: We must not forget the other person in our story, Uwe Nettelbeck. You were doing this beautiful thing in the States, and we were doing our thing on the other side of the pond, and Uwe had the merit of seeing that there was a connection between us—that these were two weeds that could grow together. Uwe had a vision and a plan. He wanted to give the experimental music the same means of production and commercial changes as Schlager or pop music.

TC: I heard this, too. I told him that if he releases Outside The Dream Syndicate it shouldn’t be classified as classical; it should be pop. Zappi, how did you get to know Uwe Nettelbeck?

ZD: It was an accident that I was there. I knew him, but I had nothing to do with film. But Andy Hertel made a film about a monk who had the same nose as me, so I acted as this monk. It had nothing to do with Faust. A bit later I met Uwe in this film house, and he brought a little suitcase with contracts and money inside.

JHP: To bury our souls!

ZD: We were very hungry so we took the money and went next door to a restaurant and ate.

TC: For me, by the end of the ’60s, this drone music was at an end. I was no longer thinking that it was a statement. As for Faust, it was a beginning, an accident, a thing that came together.

JHP: I would like to stress something that is essential to keep in mind: We didn’t think much. There was no plan or concrete intentions. We were young and enthusiastic. This is the privilege and strength of youth. I certainly didn’t think. I didn’t care. The primal ur-music is something that’s inside you. We didn’t want to invigorate, misuse, abuse, or make anything popular. No. It just happened. And Tony, you triggered this. It was latent in us, and you triggered it.

TC: It’s fantastic to hear the origins of Faust, because I never knew all of this. It’s a long and complicated story. And now the band has split in two.

JHP: I still have the sheet of paper you gave me in Atlanta where you explained your historyand your itinerary in music, but I guess you didn’t have a chance to hear our story. I feel privileged to be part of the Faust saga, and you’re right that Faust has split in two directions. We respect each other, we don’t interfere with each other, we ignore each other, we don’t like each other—but we do respect each other. The Faust story is getting complicated. Now I feel an urge to meet younger people.

TC: It was fun to begin performing music again when these younger, fantastic musicians started making their own interesting music and rediscovering what we’d one in previous decades. Getting asked to play again was partly due to the newfound access to lost music made possible by reissue CDs in the ’90s. Suddenly there was a community that was discovering this minimal record by Tony Conrad and Faust. Smart, young people like Table Of The Elements founder Jeff Hunt, David Grubbs and Jim O’Rourke found me and asked whether they could re-release our music. They wondered, “Should we ask Faust?” and I was like, “Yeah, Faust is a band—they’re real people! You should contact them.” Then they realized that Faust was actually a big band, so they invited us to play this festival. I think they were surprised that I could still play.

JHP: There was a time when I didn’t want to let anybody from the outside into our circle, but now I’m quite eager to meet all these younger people who have heard what was happening in the past and are now pushing it further. So the circle is closed to being closed. My mantra is: rund ist schön—round is beautiful. What differences have you found performing with a new generation of experimental musicians?

TC: Well, first, let me say that I’ve been working with the harmonic series for a long time. I considered the drone as a way to explore harmonic relationships. I have a lot of theories about the harmonic series that have evolved over the decades, and I’ve wanted to express them though music. So this means being highly selective about which harmonics I should play and what relationships I should establish. This approach and manner of thinking hasn’t really been developed by the younger artists working with drones. They’ve been thinking about drones, but not following this interest in a particular direction. So this is a specialized aspect of my music that I don’t see echoed so much in other peoples’ work.

ZD: Has their approach to music affected your practice at all?

TC: I’d say the rise of so-called “noise” has allowed my music to be understood in a certain way. I like noise because it breaks things up. I don’t really believe in minimalism. Okay, fine, the three of us play very steady drone music—it’s wonderful—but it’s not the only thing, you see? It’s not a matter of being impatient; it’s a matter of offering some color and some change. Yet it’s often the case that the color and change in my music is associated with the concept of noise, which connotes a sort of uniformity, so it’s a bad name for it. Because after all, there’s a lot of variation within drone music, and the types of variation that have come to be called “noise” are incredibly various. Alternative instrumental techniques, theatrical elements, different performance styles and the use of pre-recorded material: each of these things have been called “noise.” Noise is a reductivist concept. It’s such a garbage pail term. It really means nothing and it’s not an adequate way to understand what’s being added to the music. To me, noise stands for the addition of something extraneous, and I love that—to add something external. In that respect, there has been a lot of change and a lot of additions for me in what I do.

JHP: But your work with music has always spilled outside the bounds of musical performance.

TC: Of course. I think I was candid enough early on to realize that my music didn’t have a platform for achieving anything significant in the way of social change. This meant that if I had social, political or historical ideas, I would need to write or use other media to express them. There were certain observations I made that suggested that social change was a good area to be thinking about. It seemed to me that rock ‘n’ roll was a really significant factor in the downfall of the Soviet Union. Jeans, fashion and rock ‘n’ roll infected the East in a way that was very powerful. I think this helped to draw my attention to the way that music may function as an expression of social power and social twisting—the twisting of individuals in the construction of a social order. The clearest examples of this kind of thing are marching music, anthems and church singing. It’s very clear that music is one of the main things that forms identity and creates unified social structures, so the idea that you’re German or American is strongly expressed through music.

Also, music in relation to advertising—jingles, for example—is very important to social constructs. Everybody thinks that all of this isn’t such a big deal. I think it’s way up at the top in terms of importance. It’s very clear that these are factors that have been inaccessible to a 20th century understanding of music and society. In the 21st century, we’re going to need to understand some of these things as we face the pervasive monster that is neoliberalism. And we have so few tools that actually manipulate people in any way that could be construed as opposite or running in a different direction to neoliberal forces. If we ignore music in this regard, we’re making a big mistake.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2015 issue of Electronic Beats Magazine. Click here to read more from past issues.

Published April 11, 2016.