Techno Deity Jeff Mills Meets Art Star Ólafur Elíasson

Detroit native Jeff Mills is one of electronic music’s great conceptualists. Treating techno as an art form that transcends dance floor euphoria, his musical investigations of science fiction and utopian themes overlap with the work of Danish-Icelandic artist Ólafur Elíasson, whose large-scale installations explore the manipulation of space, light and reality. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Eliasson has long found inspiration in Mills’ work, and vice versa, which is why when getting to know each other for the first time, talk of art education and collaboration had both artists buzzing with ideas.

Ólafur Elíasson: I remember when I first encountered your music. It must have been 1997 or 1998, and I had just moved to Berlin a little while before. I’ve always been very interested in the structure of sound but I wasn’t very articulate about it back then. I’m still not, really. But sometimes you hear things that seem to be expressing themselves on your behalf. Sometimes you go to a concert or to a club, and you hear something that is almost like it’s verbalizing something that you wanted to say, but you hadn’t quite found out what language to say it with. I had that experience with your music. And if that happens, the interesting thing is that you connect to the sound so that, in a sense, you become the producer of the music. You identify with it to such an extent that it becomes a part of you. I haven’t found out exactly how to coin that phenomenon, but I think you, Jeff, have successfully created sounds that speak on behalf of others over the years. Personally, back then it had a lot to do with having left Denmark, coming to Berlin and starting to make my works.

Jeff Mills: I wish I had met you then. You can probably relate to the fact that when I create something, I’m kind of lucky if I can retain that type of relationship with it. In most cases, I become the spectator of my own work. The public’s opinion kind of takes over. It takes it away from the creator, whether you want it to or not. I’ve produced things where I’m kind of in disagreement with other people’s interpretation. It can happen. There’s always that risk. So I’ve resorted to a way of just making music for myself and not letting anyone hear it, and I listen to it only to inspire myself to realize something else.

OE: Wow, that’s a great luxury.

JM: Do you ever do things like that?

OE: I search for places that will inspire me. To be inspired is actually hard work. I really respect the people who somehow seem to be inspired out of the blue. I always have to bloody listen or read or work on something to achieve that. When I stop and pause, I literally stop getting inspired. I wonder what would happen if I really took a break from working. I haven’t tried that for 30 years now. But essentially, I don’t know if I make works for myself. But I like to experiment and those experiments very often don’t turn into anything. There is that moment where an experiment sort of turns around and takes on its own agenda. So instead of you pushing it, the experiment pulls you with it. This turning moment sort of indicates that what you work on might potentially be artistically valuable. But this doesn’t happen very often. You keep pushing and pushing, and it just gets more frustrating and, eventually, nothing comes out of it. Then again, ten projects that do not turn into something bring you to another point.

But I’m curious about the consequences of working with sound. If you think of a soundscape, or an architecture of sounds, it’s very spatial. It’s not a linear thing that goes out of the speaker and comes into your ear. It’s the whole environment that is somehow vibrating or pulsing, and it’s very three- or four- or five-dimensional. How does that feel, and what happens to you when you are in that space?

JM: I really believe that all humans, no matter how many people they’re connected to or how many friends they have, really spend most of their lives by themselves. You experience things in ways that are very difficult to explain in words or in conversation. I always think about that when I’m composing music. I’m never really composing for people, but for an individual listener. There’s a whole bunch of psychological aspects that go with that.

One thing, for instance, is that for most of us, we graduate from college if we’re lucky, and then after that, structural and formal teaching is really over. The average person doesn’t really have many opportunities to realize new things because they have their life, a family, responsibility and so on. And so I always thought that if we can slip more things that are relevant, more teachable things inside of art, using music to whisper something to someone to kind of nudge them in a certain direction, this feeling of learning in a very structural way then takes over. I always keep that in mind when I’m sitting in my studio alone and I’m thinking about the way that I would like to learn about new things. Ideally, it would be through something that I enjoy, like electronic music, science fiction or classical music. And I wonder, why can’t I learn something about planets at the same time?

OE: That’s a very valid point. It points towards what type of active role, if not music, then creativity and artistic agendas, can bring to our society in the future. Because I do think there is a tendency to think that creativity is something that you consume. When you go to a museum or a concert, you do that in your spare time as a kind of recreational escape. I am not a fan of education in words, as it is a bit patronizing in this context. But the idea of having confidence in people being able to evolve is, I think, one of the great strengths of cultural production. Because when you go to a concert, people are not being patronized; you don’t first walk out and explain this sound means that, and that sound means this. Essentially, you let it flow and people just have an experiential relationship with it, which is very much driven by trust. There aren’t many places where people can exercise trust with such precision.

If we look at society as a whole, one of the great challenges is the lack of a feeling of interdependence: to trust the politicians, to trust the finance sector, to trust the scientists who work to fully understand climate change and how to deal with it. So trust is a major issue. And cultural production, if it is not marginalized into some kind of experience economy, is fundamentally trustworthy. It’s the strongest parliament of our times; it’s creativity. I totally agree with you that there should be no limits to where one can take these things.

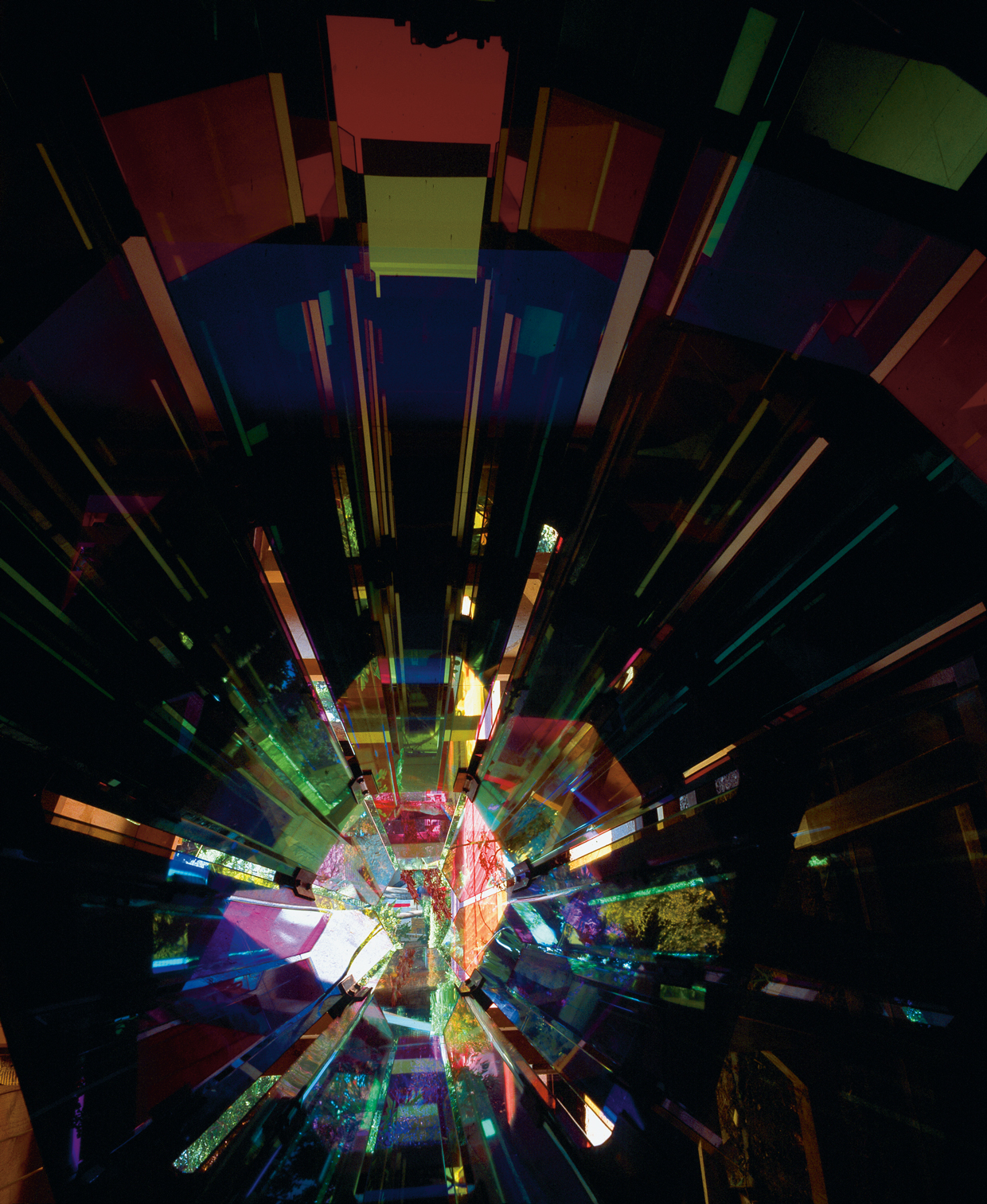

JM: I went to see The weather project when it was first shown in Tate Modern [Gallery in London directed by EB contributor Chris Dercon]. It was the first time I was exposed to your work. What was most interesting was the way that people behaved when they first saw the installation. It was literally like they were seeing Jesus in front of them. And they began to walk very slowly and their movements began to slow down, actually. Some lay down on the floor, some became more quiet and started whispering to one another. I’ve never seen that before. I’ve never seen an installation have this much power.

OE: I was struck by the experience of the people as well. I often think about it. As you mentioned, a lot of people did a lot of different things, and yet they were not seeing the diversity and activity in the space as a conflict or disturbance to the experience of the piece. I’m very curious about what types of environments actually see difference as a success. In Europe we have a lot of exclusion going on right now based on difference. Different cultural background, different religion, different skin color, all kinds of things. And in that sense, I’m curious about what types of spaces successfully acknowledge that people see things differently; they are different, they come from different places, and that this is actually a contribution to the quality of the space.

When you say, “Oh, that sound. I didn’t really like that,” and someone else says, “Actually, I kind of liked it. It sort of touched me,” you can still be friends. And we don’t think that’s remarkable, right? But the truth is, that’s actually quite a big deal. If you see a position in politics, everybody says something and then uses the differences in their points of view as an excuse for acting politically. I’m very interested in the question of why we are so touched by sound. It’s so irrational. And why are we not using sound and music to teach mathematics in school? It has unbelievable potential, yet it’s somehow just sitting to a great extent in a very passive or, let’s face it, stupid industry. Or it’s an art form that, just like the art I do, is a little bit elitist and marginalized for a certain group of people. That’s why your thoughts on teaching resonate so much with me. And I don’t just mean bringing music into school. Maybe it’s also about bringing the school into music.

JM: I think that there will be a great change in the way that we learn. When I was in high school, we never finished the book, meaning that whatever class it was, we never reached the end of the textbook. And that was routine in Detroit public schools. So what does that tell us? I think that the old ways of teaching won’t be enough. I think that probably the best way to teach a human will be to simulate reality so they not only open up a book and read it, but they have the opportunity to feel like they are experiencing it firsthand. And I think that we may be entering into an era where virtual reality and the simulation of reality are better teaching tools. Because you not only feel that you’re there, but you can experience it from different perspectives. You can be taught the Civil War in the U.S. from the Confederate side and the other side. You can be caught in between. So I think we’re just on the edge of using art and sound and all these things to teach.

Technology will have its most profound use there—I think it’s going to replace education. And I think when that happens, we’ll be looking at art and art forms very differently. Not only can you listen to Miles Davis, but you can also understand the context in which he made Bitches Brew, or the first time that he played at Carnegie Hall. I think that in the end, we will become, in a utopian kind of way, super-human, super-intelligent, not because of the books that we read, but the type of experiences that we’ll be able to live in our short lifespan. So I can be a fireman on Tuesday, I can be the president of Ghana on Thursday, I can be back home and watch my soap opera on Sunday. It may be like that. And then when you think about experiencing things outside of here, other planets, going to Mars, and having the feeling of walking across the surface of Mars and what that would be like, it’s going to be an enormous leap forward. And I think art, music, all these things will have incredible impact as teaching tools.

OE: Since you were at my studio yesterday, maybe you saw that we have a number of digital spatial experiments with these Oculus Rift glasses. We 3-D printed a camera that has hexagonal filming capabilities of the space, with six GoPro cameras in it. What I’m interested in is the link between the virtual and muscle memory, because I do think people totally underestimate the experience that one has. Of course it’s not the same as being on Mars, clearly. On the other hand, it allows for storing knowledge in a spatial and bodily way much more complex than pure theoretical or algebraic teaching. And this is how culture and sound and music and art and theater have been operating for a long time. It has always been physical. And I do think that we see more and more education and training and skill enhancement, involving culture as a guiding light. We are searching for ways to store knowledge in our bodies or brains in more sophisticated ways.

JM: But you also teach as well, right?

OE: I did. When I taught at my former school, The Institute for Spatial Experiments, I made a point to explain something very specific to the students, or “participants” as I called them. They would come to me and say, “Listen, I have a great idea.” And they explain the idea and say, “Isn’t this a great work of art?” And I say, “No, it’s an idea about a great work of art, and you are about to go on a lovely journey to try to turn this idea into action. And this is one of the most rewarding things one can do.”

The journey is in fact first a sketch, then a model, then another sketch, then many models, then going back and forth reading a bit about it, asking a scientist for guidance or assistance, having people help you, testing it on a bigger scale, and so on and so forth. And gradually, the idea gains physical space. I’m very interested in this process, when an idea leaves the state of language or intuition and gains physicality. This is what I call “reality production.” Eventually it might even be shown in an exhibition, but that is just another creative step. And I think it’s important to see that the creativity in this isn’t in taking a sketch and turning it into a model. The creative part, I think, lies in understanding the consequences that creating art has on its surroundings on the other students, on the world, and how the world inspired you to take that step in the first place.

So this means that what makes things creative or gives them potential is actually not what I do in the studio. Rather it is in the consequences of having a studio that creativity arises and inspiration is nurtured. I think this is very important to understand for teaching, because there seems to be the suggestion that you can teach in a closed environment, a school, whereas the criteria of a potential success of a school should be rooted in the frictional quality it has with our times. And I do think, in a very odd way, this is why at some point, Detroit realized that they were alone. And this is the moment when they started challenging that idea. And out of that challenge, people like you emerged.

JM: I think that we aren’t able to detach ourselves from the problems in which we grew up. And I think that when they go to Mars, they’re gonna take Earth problems to Mars. If you have a man and a woman, a young and an old person, somehow they’re going to bring up these differences, and they will create the same world that we exist in now.

OE: Well, the reason why I’m optimistic is that I think that sometimes, even without knowing, we take it for granted that reality is non-relative. Reality is relative. We live with things that we mistakingly think are pre-defined, given by God, made by nature, and we say this is beyond the reach of negotiation. And if you take a different stance and say everything, including reality, are models—especially social conventions or cultural conventions—then the way we see things is cultural. We don’t see reality, we see things the way that we’ve learned to see things. That’s why I always insist that reality is relative, much more relative than you would normally think.

One great area to rehearse your relationship with reality is, for instance, culture or art or sound. Because I do think that it’s a very healthy exercise to counter the essentialism that comes with saying, “This is something God decided. Nature is predefined. That’s how cities look. This is how architecture has to look.” Things are the way they are because of the social regimes with which our society has chosen to organize itself. To criticize that can be very liberating. I do think that one can actually adapt to major changes, because we see that, well, reality is not real anyway. So we might as well just change it. And that’s why I’m generally quite optimistic with regard to the confidence in people’s ability to shift or adapt to new environments.

A good example is the way I listen to your music. It’s almost like there is a huge area or infinitely large space of what we all know. These are the things that we learn, and this is the world that we understand. Then there is a threshold, and then on the other side of that border or threshold, there is everything that we do not know. And that’s my very simple version of the world: the known versus the unknown. And our life, to a great extent, consists of expanding the known into the unknown. The older you get, the more you know. Or so we hope. But walking up to that line is reminiscent of how I think of your music, which is the meeting of the two. Right? That’s the sound of that line between everything we know and everything we do not know yet. But by listening to it, we kind of expand. Because then we’ve heard it, then we know it, and before we heard it we did not know it and it was unknown, right?

The idea that you could walk up to your own horizon I think is a lovely one. We kind of make the mistake and think the horizon is always moving with you as you walk, no? I think you just walk up to your own horizon and say, “Look, actually the horizon is not a line, it is actually a space.” It is a space in which things are both familiar, known, and they are also abstract, unknown, at the same time. And there’s actually plenty of stuff in there. One can build a house in there, one can live in that horizon, where you adapt to the unknown and you have a lot of known stuff with it. So when I make a work of art or exhibition, I very often try to think about, well, if this is now the end of everything known, let’s say the galaxies, the Milky Way, the horizon of the Milky Way, beyond that there is the other thing. Let’s say the exhibition is right there hovering in that infinite emptiness.

JM: OK, I have another question. Could you ever imagine that your artwork could become a living, breathing thing?

OE: Oh yes, absolutely. I say it also because I think as a rule, one should never suggest no-goes in art. The way I see it, art is more a language, and the language can be anything, everywhere at anytime. It can be anything at all. I have gradually learned that. But what is much harder is to say something interesting with a language. I think that requires a lot of talent to stay connected somehow, so that you know that what one does is interesting. You have worked so long now, Jeff, also, clearly to stay on top of…I don’t mean career or anything like that, I just mean creativity. To be creative requires a lot of, for lack of a better word, connectivity with the world. You have to be able to feel what is going on, not just around you, but just in general. On other planets, for that matter.

JM: I’m Afro-American, which means that as with other Afro-Americans, I don’t really know where I’m from. So we have to make up and construct a hypothetical past and then create a reason for living from that. So it’s different, because we’re not really tied to anything or anyone or any place. We have a notion that we’re from a certain continent, but we don’t really know, and we don’t really have those ties. So at a certain point in our lives, we really have to make it up, and as a result, you don’t really have many boundaries. Nothing is outrageous. You have Sun Ra and people that literally just create their personal history, and no one can tell you that it’s not true.

I wouldn’t say that Afro-Americans are prime candidates for creating surrealism, but our typical circumstances lean more to the idea that we need to live, and we need to have some basis for living, so there we create our world and our purpose. Music is a device. It has always been something that we can use to manipulate, to create, to use as an extension. But it’s really a world that we live within. And it’s a world where there are no rules, there are no laws, there’s no one telling you what it should and should not be. Of course we have critics, but the truth is that you have the ability to be able to move mountains if you can find the right code. We know this, and we treat it almost in a religious way. And somehow it’s handed down in Afro-American culture in a special way that we hear it differently, and we can interpret it differently. I don’t know where it comes from—it’s not something we’re taught in school, it’s not something we can read and understand. It’s rhythm, it’s a very natural thing. I’ve never had any conversations with really old black people about it, but it’s a very instinctive thing, and if you’ve done it as long as I have and you do as many things, it really becomes one of the few things you can really rely on.

OE: I think that as the world grows more complex, the idea of identity also changes. Traditionally, identity was very strongly defined by the past. I think there is an increasing tendency to say, “Well, my identity is the compilation of moments to which I belong.” And that belonging very often transcends national borders. I might have more in common with a guy in Japan than with the person living next door. But even though we have cultural landscapes and identity patterns that are shifting so fast, it does not replace the need for having a sense of history and belonging in the trajectory of time. I do think it’s important to see that identity also needs to be seen as something extending into the future, the trajectory in front of you. And clearly it does not mean that one should not address holes or traumas in the past. But I think that our identity lies in how we identify with the sounds we make in the moment we make them.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2015 issue of Electronic Beats Magazine. Click here to read more from the magazine.

Published October 15, 2015.