TYGAPAW Digs Deeper into Techno’s Black Origins

On 'Get Free', the Brooklyn-based artist imbues peak-time techno visions with themes of Black liberation and sovereignty.

I first discovered The New Dance Show a few years ago in a late night internet rabbithole thanks to YouTube account Caprice87’s meticulous uploads. Caprice is one of those active YouTubers whose commitment to the form is unmatched. Other users consistently tag Caprice in comments on old recordings to ask for a track IDs, and Caprice, with a deep knowledge of the halcyon days of Detroit techno, unfailingly delivers the answer.

Caprice87’s particular obsession is the Soul Train-indebted Detroit dance music television program that ran on local station WGPR-TV 62—the first Black-owned and operated television station in the country—from 1988 to 1996. Instead of Chicagoans grooving down the Soul Train line in high-waisted, flared jeans to the sounds of Earth, Wind, and Fire, The New Dance Show transplanted this same spirit to the futuristic sounds of the Motor City at a critical juncture in dance music history. On Caprice87’s channel, you can watch New Dance Show host R.J. Watkins hold court while dancers in very ‘80s outfits—think skin-tight, black cut-out dresses, big shoulder pads, and leopard print-lined blazers—absolutely freak it on the dancefloor to Cybotron’s “Clear” one minute and Aux88’s “Chuck” the next.

It’s a joyous treasure trove for those interested in the history of Detroit techno and electro, but for Jamaica-born DJ and producer TYGAPAW, Caprice’s uploads were a revelation. “Those videos really did spark something in me,” she says over Zoom one afternoon in October from her apartment in Brooklyn. “They inspired me to make something that creates a similar feeling and energy within someone.” This inspiration would lead her to write the songs that would make up Get Free, her debut album for Mexico City club stalwarts NAAFI. The blown out sonics and Jersey club signatures that she wove into her earlier EPs, 2017’s Love Thyself and 2019’s Handle With Care, sound perfectly attuned to the what you might hear at any given Fake Accent, the long-running, New York City-based club night that she curates, but her new album leans a bit more heavily into what most would consider straight-up techno territory. Its songs sound as if they’re directly descended from peak 1990s Jeff Mills and Underground Resistance, both in their unrestrained, raw sonics, and precise political messaging.

Let’s fuck something up and figure something out.

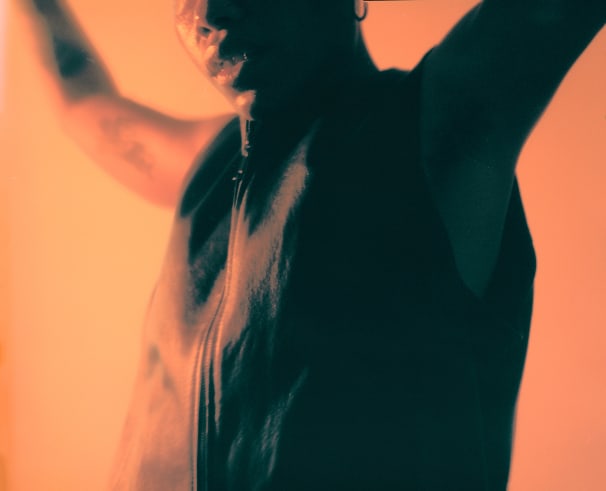

When we speak over Zoom, TYGAPAW’s hair is dyed acid green and cut short—just shy of a buzz cut. It’s the same length pictured on Get Free’s cover, which was shot by her partner, Avion Pearce. At first, they were thinking of making something more kitschy, but they decided on an image that better matched the drive of the music: Bathed in orange light against a peachy backdrop, the nude portrait feels similar to a still-life image of an ancient Greek sculpture. TYGAPAW readily admits that it’s an instantly iconic image. “I wanted to stand as a symbol of empowerment,” TYGAPAW explains, “but not cheesy—more like, let’s fuck something up and figure something out.”

She explains the collaborative energy behind the shoot, which in itself was a decision that she had to advocate for in order to get full creative license. “To me, that cover shows the beauty that comes out of sheer determination. That has been most of my career. Getting excellent, incredible shit out within very meagre means and constantly being questioned and doubted in terms of what my abilities are,” she says. The image is just one minor example of the imposed doubt that she’s always face-to-face with, and she casts this apprehension in the light of the Black Lives Matter movement’s politics of visibility. “All of these brands and organizations want to be supportive of Black artists, but it starts on the ground level. It starts with just acknowledging and understanding that things are not equal and our labor is not valued,” she says.

This sense of persistence has always been a part of the raw fabric of her music, but Get Free isn’t quite the album that TYGAPAW thought she’d be making this year. Pre-pandemic, she wanted to delve into her roots and create a full-length album centered on marronage in Jamaica. “It’s the act of liberating slaves from the plantation and assimilating them into the rural communities. I thought that was pretty badass,” she says. As she explains it, these were free communities first established by enslaved Africans in the 15th and 16th centuries, when Jamaica was colonized by the Spanish, and the practice continued into the 1800s under British rule. This May, TYGAPAW was supposed to go to Mexico for a festival gig and then back to Jamaica for a few days to do some research to further excavate these ancestral stories. She still hopes to follow through with that project one day in some capacity, but she shifted her focus given the global lockdown and the social and political unrest that followed.

In June, during the apex of the Black Lives Matter protests in New York City, she recorded and released Ode to Black Trans Lives. The EP is a collaboration with scholar D-L Stewart, whose vocals defiantly claim Black trans sovereignty as TYGAPAW’s furious breakbeats threaten to careen off the rails. Just a month later, TYGAPAW started working on Get Free, which is still steeped in the memory of maroonage even if it’s not quite the heady concept album that she originally had in mind. “It’s still upholding the meaning of Black liberation and rebellion,” she says. “Now more than ever, I felt that I wanted to create something uplifting and that I feel celebrates Black people, especially as the protests started happening in the middle of it.”

Get Free is anchored by a collaboration with artist and writer Mandy Williams Harris, whose liberatory poetry flows throughout the album, speaking of serenity, self-criticism, and sovereign land. The two met a few years ago the first time TYGAPAW played in Los Angeles, but they reconnected only last year at a dinner following another one of TYGAPAW’s sets. “I was always very drawn to Mandy’s words and art and how beautifully she could articulate the Black woman’s experience and how important it is to stand up for Black women,” she says. Though TYGAPAW goes in and out of Patois every now and then on the record, it’s Mandy’s writing that ultimately bridges the melancholic melodies and throwback acid basslines with the concepts of personal freedom, community, and tenacity that Jamaica’s history of marronage brings to light.

Now more than ever, I felt that I wanted to create something uplifting and that I feel celebrates Black people.

It’s a history that TYGAPAW had to extract from the tidy colonial narratives that she was taught as a child. “We don’t learn how powerful our ancestors were and how they were able to maintain freedom while two nations were fighting over our land,” she says. “It’s crazy how much brainwashing there is and how—even if you’re of African descent—that empire is ultimately what we should identify with. Jamaicans are so incredibly powerful and beautiful because they culturally denounced that with Rastafarianism and Garveyism—that all points to us empowering ourselves.”

The maroons brought together people of African descent and the indigenous Taíno and Arawak tribes, a complex social dynamic that’s been purposefully dulled in written narratives. “Our history is intentionally misleading so we don’t feel connected, and so we don’t feel any sort of claim to our land,” she says. Harris’s words in “Ownland” seek to rectify this, setting forth a vision of liberation and healing that starts to fortify this latent connective tissue: “Sunken voices call from the depths/To remind us that they were unafraid,” Harris begins. “And in due terra incognita/To feel in kilojoules as the smallest glint/As the feeling in the fullest body of worth/We will find our own land.”

TYGAPAW explains the gradual shift to the techno-focused sounds that envelop these narratives, which you can trace by listening to her output in chronological order, to her natural growth as a DJ. “Over the years, I’ve gone from just playing locally in New York to traveling around the world and playing Europe and Asia. That completely expanded my horizons—being immersed in those spaces and just being a sponge absorbing everything.” This wasn’t just a surface level evolution. Everything that TYGAPAW makes is firmly rooted in a continual process of diving deeper to recover knowledge that’s been obscured by dance music narratives that center white bodies and voices. “This led me to seek out the knowledge that has sort of been erased from Black culture and that’s been kept from us. If you can’t relate—if you’re not really seeing your ancestor creating the music within that space—people are always like, ‘Why are you doing that shift?’ and it’s because I discovered that Black people made techno,” she says. “That’s the bottom line. That was my eureka moment.”

When she first became immersed in New York City’s nightlife scene, it was ballroom that initially captivated her captured her heart. Over time, her interest in club music led her to analyze increasingly precise elements that she felt drawn to. She wanted to know how exactly the drums on Zebra Katz’s songs were programmed, how breakbeats worked, and how to incorporate faster BPMs. It’s a learning spiral that she says she’s still coursing down, carefully peeling back sonic layers to dig deeper and deeper. “The difference between me and other people is that I was never afraid to release music and expose any of my underdeveloped skills. I’m not too afraid. It’s a blessing to be alive at this point because you get to try things out and get feedback immediately through the Internet. That’s a really great way to grow as an artist, if you’re really open to it. Your public is your teacher, especially because Black women don’t get access to musical mentors,” she says. “My musical life has just been trial and error, heavy listening and learning as I go. You can’t fault anyone for figuring out things as they go, especially when you don’t have access to anything.”

She’d always been innately drawn to the sort of unbridled dancefloor energy that she’s crafted on tracks like “Run 2 U” and “Facety,” even back when she was an adolescent listening to The Prodigy, but it took her a long time to explain exactly why. “Where I come from, Jamaicans will clown you on some shit about electronic music,” she says. “If you try to bring it up or you try to play techno, they’d be like, ‘What dat? White people tings!’” she says, breaking out into Patois. “They’d just be shady with that kind of music, but then you find out that wait, it’s for us. That’s really what it is.’”

Your public is your teacher, especially because Black women don’t get access to musical mentors.

It’s precisely why watching those old New Dance Show clips resonated so much with her, and why discovering even more about the pioneers of techno through a jungle documentary on YouTube opened the floodgates. “Hearing the total story of Underground Resistance and all of the people affiliated with Detroit techno just opened everything up. I was just like alright, I don’t have to second guess myself. It’s something that I love and something that I’ve always been curious about, but I always felt very outside of it and that I didn’t belong there. Why do I want to try and force myself into it? I’m not a white man, and I don’t feel entitled to spaces,” she says. “But learning how it was taken from us—and nobody wants to take accountability for that—now I’m at the point where I can confidently go forward and say that this is the type of music that I want to make. I feel very grounded in it.”

I ask her if she’s planning on recreating The New Dance Show with her own music in the background soundtracking the scenes of unfettered Black joy and self-expression. She says that she’d like to one day, but she wants to be very intentional with the way that she represents her references and influences. “I don’t know if anything is original anymore,” she says, questioning the idea to make her own New Dance Show music video. “But you really have to give credit where credit is due. Our forefathers did some amazing shit,” she says. “We have all that to draw from. Fingers crossed.”

‘Get Free’ will be released via NAAFI on November 13. Support the artist on their Bandcamp.

Rachel Hahn is a writer based in New York. She writes frequently about music, art, and fashion.

Photos of TYGAPAW by Avion Pearce.

Published November 11, 2020. Words by Rachel Hahn, photos by Avion Pearce.